Rating: D

Dir: Freddie Francis

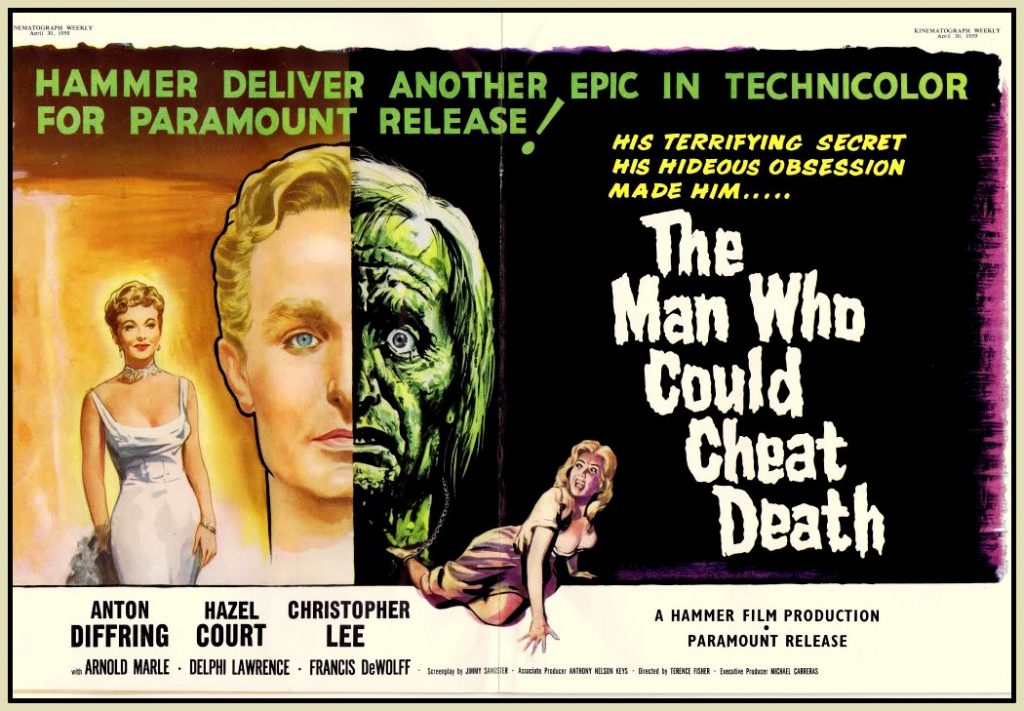

Star: Anton Diffring. Christopher Lee, Hazel Court, Arnold Marlé

This is a thoroughly forgettable and underwhelming mad scientist movie: you wonder how it might have been different. if Peter Cushing had starred in it as originally intended, rather than Diffring. Cushing dropped out shortly before filming was due to start, citing exhaustion. This caused no small amount of friction, with threats of lawsuits being tossed around, though nothing came of those, and Cushing continued to work for Hammer. Diffring was able to take over the role, and had played the role in a TV version of the story in 1957; Marlé also reprised his part from that version. Both were adaptations of a play, The Man in Half Moon Street, which had already been turned into a film in 1945, starring Nils Asther.

The Hammer version relocates the action to 1890 Paris, for little apparent reason beyond their usual Euro-totty enabling. We’ll discuss that more in a bit. There’s certainly little or no French flavour here, beyond the opening scene of a gendarme sporting both a moustache and a kepi. Dr Georges Bonnet (Diffring) is a sculptor/doctor, having a soiree to show off his latest creation. Arriving there are Dr. Pierre Gerard (Lee) and his date for the night, Janine Dubois (Court). Which is a bit of a shock to Bonnet, as he had recently enjoyed a fling with Dubois while on holiday in Italy, before ghosting her. Before anything can happen there, he has an argument with his current model. who wants more than a job. The doctor turns green and apparently secretes acid, as his grasp burns her face. Something weird is clearly going on.

It takes about 25 minutes of faffing around before the film comes out with what passes for an explanation (the acid touch is never mentioned). Bonnet is actually 104 years old, and has been invigorated by once a decade transplants of parathyroid glands, carried out by colleague Prof. Ludwig Weiss (Marlé). These come from not exactly willing donors, so every ten years, Bonnet has to relocate. He’s now approaching his next scheduled procedure, and is currently subsisting on an extracted serum every six hours, without which he becomes violent and irrational. However, there’s a problem. Weiss is now too old and shaky to carry out the operation, so a replacement needs to be found.

The professor talks Dr. Gerard into taking over, but when Weiss vanishes – the victim of one of Bonnet’s rages – Gerard withdraws his agreement. To enforce compliance, Bonnet abducts Dubois, saying he’ll only release her after Gerard does the transplant. On that side of the plot, it turns out Dubois is still in love with Bonnet, and has agreed to go away with him. Though this decision may be on slightly thin ice after the whole kidnapping thing. Can Gerard and the authorities locate and rescue her before Bonnet performs his decennial disappearing trick? And maybe – just maybe – the mad doctor will suddenly find the hands of time creeping up from behind, ready to give him a back rub.

This film’s origins as a stage play are obvious, the vast bulk of it taking part on about three sets, with few outside scenes (and what little there are, are typically drenched in fog). It’s also extremely talky, with discussion between the three professionals on the topic of medical ethics occupying a significant chunk of running time, and not being very interesting. The problem is that, unlike Baron Frankenstein, Bonnet is pushing the boundaries of scientific morality for purely selfish ends, not scientific advancement, which makes him a considerably less ambivalent and sympathetic figure. Indeed, there isn’t really a hero here at all. Gerard might be closest, except the first half fails to establish him as more than Dubois’s arm-candy.

Speaking of glands, the “continental” version of this infamously includes a topless shot of Court (you’re welcome!), modelling for the doctor: she was paid an extra two thousand pounds. But her character is French, so it’s okay; it’s what they do. This wasn’t the first time the European edition had been spiced up: The Mummy had similarly foreign babes, i.e. Egyptian handmaidens, showing off their, er, pyramids, in a scene allegedly shot by producer Michael Carreras without director Fisher’s knowledge. But this was the first time a Hammer leading lady would undress: while it would become a studio trademark, this was still the fifties, and considerably more daring. Needless to say, the shot was optically cropped here, and the BBFC also insisted on the fiery fate of Bonnet being substantially cut back. None of the excised footage has ever been restored for any subsequent release.

I couldn’t help thinking it might have worked better if they’d kept the original London setting, and moved it a just a couple of years earlier. It could then have tied the doctor’s search for glands, in with the Jack the Ripper murders, terrorising the East End in 1888. Or perhaps emphasized the change in Bonnet’s personality when he’s off his meds, going down the Dr. Jekyll route. Instead, it’s an uninteresting and sloppy script by Jimmy Sangster. One character we’re given every reason to believe is dead, suddenly resurfaces at the end, against all story logic, and Bonnet’s acidic sweat drifts inconsistently through proceedings. The final make-up job is, frankly, an embarrassment. Bonnet looks less like he is rapidly aging, than undergoing an invigorating facial.

It’s tough to call any Hammer film a dud, yet this one comes as close as any to the current point. While the cinematography and most other technical aspects remain sound enough, it’s an underwhelming idea, that isn’t lifted up by the execution. It is nice to see Lee unencumbered by make-up or silly hats, and that’s about as kind as I can be about the movie. Even at the time, it was regarded in most reviews as being far more tell than show, and I can’t help thinking that Cushing’s decision to bail on the production was a wise one. Viewers who opt to do the same won’t be missing much.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.