Rating: B-

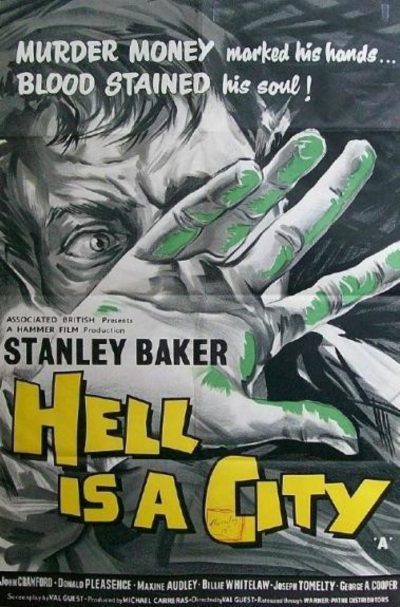

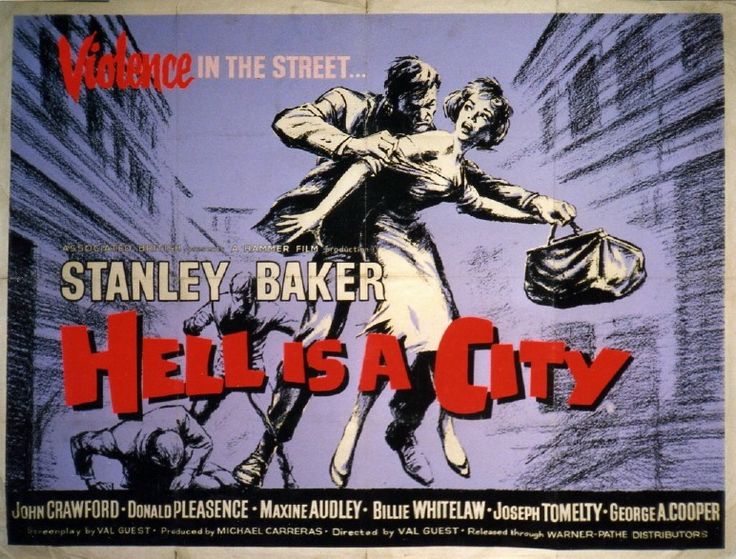

Dir: Val Guest

Star: Stanley Baker, John Crawford, Donald Pleasence, Vanda Godsell

Much like Never Take Sweets from a Stranger, this is a Hammer film which doesn’t particularly feel like a Hammer film, being entirely devoid of any fantastical elements. This is thoroughly grounded in grubby, urban reality, with the studio making a relatively rare departure from their regular Home County stomping grounds, and shooting on location. The titular city which is hell turns out to be Manchester – so, nothing has changed in 60 years then, hohoho – with its mean streets being patrolled by Det. Inspector Harry Martineau (Baker). He’s a career copper, whose devotion to his job is putting Martineau’s marriage under increasing strain.

Matters aren’t helped by the escape from prison of Don Starling (Crawford), a criminal that the policeman helped put away, and who vowed to take revenge from the dock. That angle is quickly discarded, with Starling instead seeking to raise the necessary finances to allow him to skip the country, and also recover the loot from the heist which got him his fourteen-year stretch. The former involves robbing local bookmaker Gus Hawkins (Pleasence, already short of hair despite being barely forty!), but this leads to the murder of the young woman carrying the cash to the bank. Combined with the death of a prison guard during Starling’s escape, it’s clear to all he’ll swing if caught – capital punishment wouldn’t be abandoned in the UK until 1965. And that means Starling has nothing left to lose, as he seeks to avoid the tightening police dragnet.

This is a rare Hammer movie to be award-nominated. Guest’s screenplay, based on Maurice Proctor’s novel, was nominated for a BAFTA, losing to Bryan Forbes for The Angry Silence, and so was Billie Whitelaw, for playing Hawkins’s wife, who has a history with Starling. Hers came in the “Most Promising Newcomer” category, which went to Albert Finney for Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, so no great dishonour there. Despite this, it’s a film which does not seem to be regarded in the same way as similarly gritty films of the period such as Room at the Top, which formed the “British New Wave” cinema movement. This is certainly every bit as grounded: even though Martineau has a nice house, he moves with ease (and of necessity) through the working-class world. Among the crooks, he has a reputation as someone who’ll act fairly, rather than “fitting them up” on false charges.

This is a rare Hammer movie to be award-nominated. Guest’s screenplay, based on Maurice Proctor’s novel, was nominated for a BAFTA, losing to Bryan Forbes for The Angry Silence, and so was Billie Whitelaw, for playing Hawkins’s wife, who has a history with Starling. Hers came in the “Most Promising Newcomer” category, which went to Albert Finney for Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, so no great dishonour there. Despite this, it’s a film which does not seem to be regarded in the same way as similarly gritty films of the period such as Room at the Top, which formed the “British New Wave” cinema movement. This is certainly every bit as grounded: even though Martineau has a nice house, he moves with ease (and of necessity) through the working-class world. Among the crooks, he has a reputation as someone who’ll act fairly, rather than “fitting them up” on false charges.

He’s helped by local barmaid Lucretia ‘Lucky’ Lusk (Godsell), who makes her interest in the detective plain, and who also has a past connection with the fugitive. It’s all very nuanced, in that outside of Starling, most characters are morally grey. Even his former associates in the underworld are very reluctant to help him given the violent nature of his recent crimes. The scene which illustrates this best has Starling call up ‘Furniture’ Steele, threatening Steele’s mute grand-daughter if he doesn’t give Starling a place to hide out: “Something not so nice could happen to her. And she wouldn’t be able to scream.” Showing what can only be called balls of Steele, the grandfather fires back, “Now listen here, Don Starling, anyone around here will tell you I’m a man of my word… Yes, I’m threatening you. If you or any of your pals come anywhere near my grandchild, by God I’ll shoot you.”

Another cultural aspect which stood out was the whole “Tossing School”. Apparently, when there isn’t any horse-racing to bet on, the local gamblers in sixties Manchester go out onto the moors and gather in large groups, where two coins would be simultaneously flipped, and wagers placed on the outcome. It was apparently a whole thing in certain parts of the country, and I can only presume entertainment was hard to come by. Its relevance here, is that Martineau deduces the men who robbed the bookmaker are likely to be gamblers themselves, and potentially might be found at one of these tossing school events. This proves an effective tactic, and helps allow him to draw the net closer around Starling, by pulling in the rest of his associates.

The movie builds to a rooftop chase finale across the skyline of Manchester, with the hunted man trying to escape the lone pursuit of the detective. This is well-filmed and particularly exciting, with a real sense of potential danger. Less successful are the attempted “kitchen sink” aspects. Initially, it appears Martineau’s relationship with his wife – interestingly, he’s the one who wants kids – will form a significant element. That never materializes, and all we get is a couple more scenes of her shrill complaining. The film is considerably better off concentrating on being a hard-boiled British slice of noir, and can almost be seen as an influence on other Northern crime flicks to come, such as Get Carter.

Amusing to see Warren Mitchell, later famous as Alf Garnett, playing a commercial traveller who witnesses the robbery victim’s body being dumped by the side of a remote road. And in general, Guest makes good use of the Northern locations, both the city streets and the lonely Yorkshire moors. Although some of the accents, it has to be said, do appear to have strayed in from outside of the immediate Manchester area. Crawford, in particular, barely appears to be trying to conceal his origins, in the usual Hammer role of “actor brought in to help sell this to the American market”. Across the series to date, this has been right up there in quantity with “innkeeper” and “Euro-floozy”.

Still, this was good enough – and, going by the awards, successful enough – to make me wonder why it was a genre Hammer decided not to explore much going forward. They had certainly made their share of crime pics over the first couple of decades, but this was close to the last, with only Cash on Demand to follow. Baker, meanwhile, would go on to great success in 1964 as both producer and star of Zulu, though perhaps missed out on his greatest chance of fame. Not wanting to be tied to a long-term contract, he allegedly turned down the job of playing James Bond. On the basis of his performance here, I think he would have been rather good in the role.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.