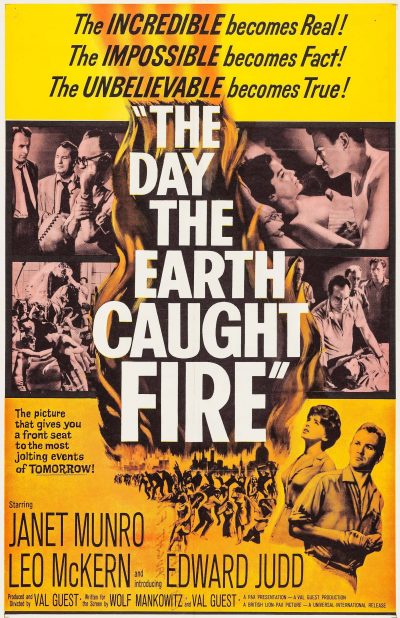

Rating: B

Dir: Val Guest

Star: Edward Judd, Leo McKern, Janet Munro, Michael Goodliffe

Following on from my review of Flood, Hal (from the appropriately-named Apocalypse Later site) pointed me in the direction of an earlier British entry in the disaster movie genre. And I’m glad he did. It’s particularly appropriate, since the previous year its director had given us our most recent Hammer entry, Hell is a City. But this is also a fine film on its own merits, even if the title feels like a long-delayed mockbuster version of The Day The Earth Stood Still, from a decade previously. [The Asylum did actually go that route, making The Day The Earth Stopped in 2008, when the Keanu Reeves remake came out]

Yet there are no aliens to be found here at all, and the misfortune is entirely of mankind’s own making. Unfortunately simultaneous atom-bomb tests, by the US in Antarctica and the Soviet Union in Siberia, succeed in knocking the Earth 11 degrees off its axis, triggering mass climatic change and geological upheaval across the globe. Worse follows, when it turns out also to have sent the planet towards the sun. In a last-ditch effort to correct things, further nuclear blasts are set off, with the aim of resetting the orbit. Just don’t expect the film to tell you definitively whether or not it works. It ends on a deliciously ambiguous note in a newspaper print-room, the staff waiting to decide whether to go with: “World Saved” or “World Doomed” as a headline. [However, the American version adds an audio coda which leans in one direction]

The apocalypse unfolds through the eyes of journalist Peter Stenning (Judd), who works on the Daily Express. He used to be a renowned writer, but a spiral of divorce and alcoholism has reduced him to creating filler articles, often requiring the help of irascible colleague Bill Maguire (McKern). When tasked with writing a piece on sunspots, he tries to get a comment from the head of the Met Office, only to be blocked by switchboard operator Jeannie Craig (Munro), who doesn’t stand for his journalistic arrogance. However, the two eventually strike up a relationship, as the world situation goes from bad to worse, and she overhears a call that allows Peter to break the story of the world’s axis having been altered. This is much to Jeannie’s distress, since she told him about it in confidence. Never mind Earth’s orbit, can their relationship be repaired before the world ends-or-doesn’t?

The apocalypse unfolds through the eyes of journalist Peter Stenning (Judd), who works on the Daily Express. He used to be a renowned writer, but a spiral of divorce and alcoholism has reduced him to creating filler articles, often requiring the help of irascible colleague Bill Maguire (McKern). When tasked with writing a piece on sunspots, he tries to get a comment from the head of the Met Office, only to be blocked by switchboard operator Jeannie Craig (Munro), who doesn’t stand for his journalistic arrogance. However, the two eventually strike up a relationship, as the world situation goes from bad to worse, and she overhears a call that allows Peter to break the story of the world’s axis having been altered. This is much to Jeannie’s distress, since she told him about it in confidence. Never mind Earth’s orbit, can their relationship be repaired before the world ends-or-doesn’t?

Guest used to be London correspondent for the Hollywood Reporter, so knows his way around the trade. The screenplay, written by Guest with Wolf Mankowitz, well deserved the BAFTA it shared with A Taste of Honey. Its dialogue fairly crackles, particularly putting over the fast and frantic nature of life in a newspaper office, when a story breaks late and hard. It’s also a look into a bygone era of carbon paper and manual typewriters, when journalistic research involved more than Googling shit. And, perhaps, one when reporters were more interested in telling the news, rather than spinning it to fit a predetermined agenda. For here, Peter and his colleagues have to break through a tough wall of official secrecy and denial regarding the situation, despite increasingly ominous and alarming events, such as an unscheduled solar eclipse. When they reach the unpalatable truth of impending disaster, should they publish and risk causing panic? Of course they should!

Given the era, the special effects are generally decent. Guest uses a fair amount of stock footage, and some of the model work is a bit shaky. But the matte effects, putting the characters in front of a largely abandoned London (top), or with the dried-up bed of the River Thames in the background, are remarkably powerful. A sepia-tinged opening, with Stenning walking through the deserted streets of the nation’s capital, has to have been an influence on the beginning of 28 Days Later. The slow grind of societal collapse, going from a world where the sun is welcomed, to one where water is available only in centralized facilities, and resulting violence and bacchanalia in the streets, is compelling. And the sudden, intense fog that’s one of the portents must have been especially resonant to an audience which lived through the Great London Smog of 1952, responsible for deaths in the thousands.

Judd gets an “introducing” credit, even though he was almost thirty by the time it came out, and delivers a sympathetic portrayal of a man who eventually realizes what’s important, and wants to be a good father to his estranged son, yet can do little in a couple of hours a week with him. However, for my money, McKern steals just about every scene he’s in, with a mix of unflappable cynicism and take-no-prisoners acid. He gets most of the best lines, such as “No woman’s irreplaceable, no matter how much you love her. There will be somebody else sooner or later. London’s full of somebody else’s,” or his description of the future as “Four months before there’s a delightful smell in the universe of charcoaled mankind.” As things break down later on in proceedings, keep an eye out for a young Sir Michael Caine, in an uncredited role as a policeman at a checkpoint.

Munro does well too, and feels somewhat ahead of her time – at least initially. She literally slaps Stenning down for his insolence, though inevitably succumbs to his rough-hewn charms later in the script, which is a bit disappointing to modern eyes. And I’m not sure the premise here made sense, even at the time. Though is it any worse than giant ants? Like Them!, this shows how, with good writing and performances, a film can sell the audience on just about anything, Once that has been achieved, and the viewer drawn in, where you go is up to the director. Even the lack of a “proper” ending here, seems less a cop-out than in line with the film’s general ambivalence to society in general. It’s perhaps good to be reminded, every now and again, that the destruction of mankind would hardly cause a ripple in the cosmos.