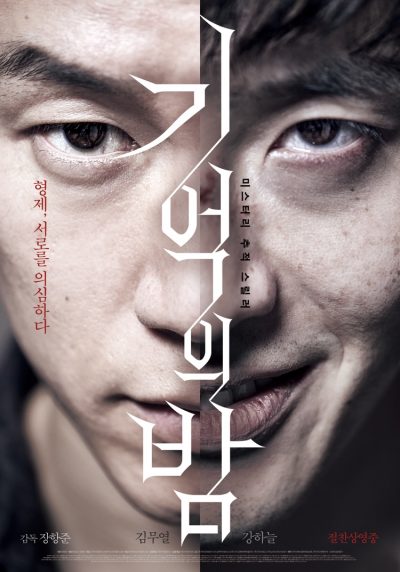

Rating: B

Dir: Jang Hang-jun

Star: Kang Ha-neul, Kim Mu-yeol, Moon Sung-keun, Na Young-hee

It’s 1987 and Jin-Seok (Kang) has just moved into a new house with his parents and older, much more successful brother, Yoo-seok (Kim). One night, Yoo-seok is dragged into a van and abducted; 19 days later, he returns, claiming no memory of what happened. But Jin-Seok becomes increasingly convinced Yoo-seok is no longer his brother: a limp, the supposed result of a car accident, provides an early clue, and when he follows Yoo-seok one night, his brother seems to be a gangster. Yet, no-one will believe Jin-Seok, who does have a history of mental issues. Is he being paranoid? Or is there something dark afoot? And what of the room in the house, which everyone is strictly forbidden to enter?

So many questions. And while I’m kinda bursting to talk about the answers, this is definitely one of those cases where the less you know about a movie, the better. Even the trailer doesn’t give away the massive swerve which takes place in the middle, after Jin-Seok finally seeks the help of the authorities. Suffice it to say, everything you know, think you knew, or at which you hazarded a wild stab in the dark, is wrong. Like so many Korean films – or, at least, so many of the ones which make it to the West – revenge is at the core of events, and once more, it’s a nation who appear to prefer their revenge chilled, with a side-plate of maliciousness.

So many questions. And while I’m kinda bursting to talk about the answers, this is definitely one of those cases where the less you know about a movie, the better. Even the trailer doesn’t give away the massive swerve which takes place in the middle, after Jin-Seok finally seeks the help of the authorities. Suffice it to say, everything you know, think you knew, or at which you hazarded a wild stab in the dark, is wrong. Like so many Korean films – or, at least, so many of the ones which make it to the West – revenge is at the core of events, and once more, it’s a nation who appear to prefer their revenge chilled, with a side-plate of maliciousness.

The resulting explanation is lengthy, and although probably necessary, does bring the film to a bit of a halt, while it crosses the t’s and dots the i’s, painstakingly explaining all the elements we’ve seen before. Hard to argue it doesn’t make sense, even if it’s several orders of magnitude more complex than I would ever be arsed to go in any quest for vengeance. The other problem which results, is your sympathies inevitably shift: again, I’m forced to tiptoe around the edges of spoilerdom, yet it’s undeniable, you won’t look at Jin-Seok the same way, once you realize the truth about the situation. None of the other characters step forward to engage the audience in his place.

Though since the film succeeds considerably more on its plot than performances, this isn’t a fatal flaw. The old saw of cinematic amnesia is frequently used as a convenient story device by lazy writers, who can have the character miraculously recover their memory at the point necessary to the script. It tends to be a painfully obvious move: while the same criticism could be made here, so much effort is put into it, there’s no way it could be considered as a cop-out. The film is told 100% from Jin-Seok’s perspective: if he doesn’t know something, the audience don’t know it either. This approach makes for a double-edged sword, yet the deliciously destabilizing sequence when the carpet is pulled out from under you, not just once but twice in a matter of minutes, is one I’ll treasure.