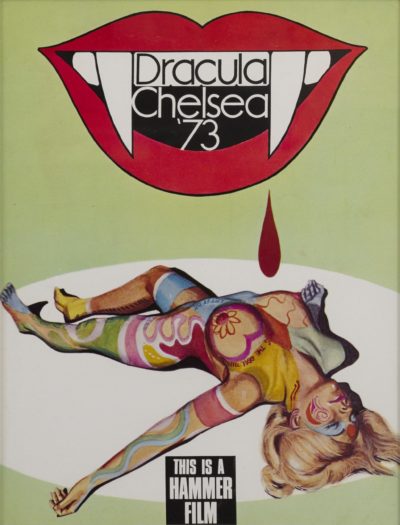

Rating: C+

Dir: Alan Gibson

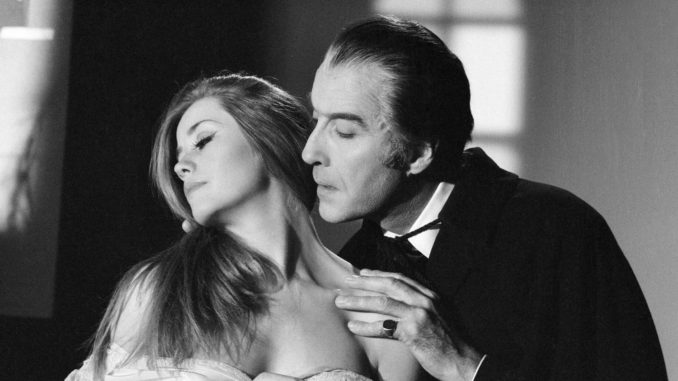

Star: Stephanie Beacham, Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, Christopher Neame

I’d forgotten how schizophrenic this is. It feels like someone slapped together two very different films into a single entity; enhancing the difference, one is great and the other is really shitty. The latter involves Neame and his pals, poncing about the King’s Road – not far from Bram Stoker’s house on St. Leonard’s Terrace – in a selection of garish fashions. Neame is the acting equivalent of nails on a chalkboard, not helped by his wannabe Satanist, Johnny, being little more than a petulant child. Witness the scene where he whines and throws a tantrum at the resurrected Dracula (Lee), about not getting powers. And who knew a Black Mass could be so tedious? It is, in the hands of Johnny Alucard. Yes, they went there. Noted vampire expert Lorrimer Van Helsing (Cushing) writes the name out, along with DRACULA, and draws lines between the letters, for the benefit of any feeble-minded audience members who took more than two seconds to figure it out.

The almost unwatchable garbage is at least moderately salvaged by the other half. It’s an “occult procedural” which sees London copper Inspector Murray (Michael Coles) team up with Van Helsing. This is because the latter’s grand-daughter, Jessica (Beacham), is part of Alucard’s crowd and so a material witness as corpses start turning up. These scenes are great, like a proto-X Files, with the sceptical Murray slowly being convinced Van Helsing knows what he’s talking about. This gives Cushing several of his brilliant exposition speeches, which nobody does better. Lee is as good as ever, too, even if after the prologue, it’s almost 40 minutes before Dracula shows up again. He and contemporary Van Helsing only share the screen in the last five minutes. That final battle is a little anti-climactic, the Count being dispatched surprisingly easily – barely an inconvenience.

This is also about the only gay (not, of course, to be confused with lesbian) tinged entry in the series, Dracula apparently transforming Johnny into a vampire, which I think is the only case of man-on-man vampirism by Hammer. Though the actual act happens off-screen, given the vast gobbets of sexual energy ascribed to the act in previous depictions, it’s not difficult to read between the lines there. Director Gibson does a good job of shifting things from the past to the present, particularly with an opening transition, which sweeps up from the Victorian Van Helsing’s gravestone, to a jet crossing the sky above London. Unfortunately, a lot of the trappings of the era, in particular the music, fashions and dialogue, have not stood the test of time. Chris, who saw this in the cinema when it originally came out, and is my go-to expert on seventies culture, seemed a little dumbfounded by some of the threads on view. She said, “I think people dressed like that more in London than New York…”

Speaking of America, for its release in the US, the feature was preceded by a short in which viewers chanted “Dracula! Dracula!” and were sworn in as honorary members of the Count Dracula society. This was by a rather embarrassing Drac wannabe, Barry Atwater, who played vampire Janos Skorzeny in the Night Stalker TV movie the same year. You got a membership card. That such a silly gimmick was deemed necessary, tells you all you need to know about this production. If you don’t have to look hard to find obvious flaws, there are elements of merit, once you peer around the hot-pants and “groovy” dialogue. They make this less than the disaster it might have seemed from the early stages.

[July 2010] I didn’t hate this nearly as much as I remembered, though the post-prologue sequence, featuring a hideously 70’s party and “introducing” a beat combo called Stoneground, made me fear otherwise. Why haven’t we heard anything of Stoneground outside this film? Turns out they’re still available for corporate functions and weddings! [2020 update: Their site appears stuck in 2006…] It has some similarities to Taste the Blood with, once again, a bunch of people carrying out a black mass for kicks, at the behest of a disciple – here, the crappily named Johnny Alucard (Neame). When Dracula (Lee) is resurrected, turns out he wants revenge on the family of Van Helsing, whose ancestor staked him in the prologue – curiously, named “Lawrence” there, rather than Abraham?

The descendants are Lorrimer (Cushing) and his grand-daughter Jessica (Beacham), the latter of whom was one of the group involved in the satanic ritual. When the bodies of the other women who took part start turning up, mutilated and drained, and the police have problems grasping what’s going on, it’s up to Lorrimer to stop his family’s enemy himself, after Dracula arranges for the kidnap of Jessica. It’s Cushing who really holds this together. Like most attempts at creating something hip ‘n’ happening, when viewed forty years later, it looks incredibly dated, with the fashions, hair, cars, etc. presented here, no more than a sniggerworthy distraction. However, when the film is not irrevocably located in 1972, it’s much better, with Beacham a decent damsel in distress, and Neame enjoyably loopy as the Renfield character – we can only presume Malcolm McDowell was unable for the part.

The descendants are Lorrimer (Cushing) and his grand-daughter Jessica (Beacham), the latter of whom was one of the group involved in the satanic ritual. When the bodies of the other women who took part start turning up, mutilated and drained, and the police have problems grasping what’s going on, it’s up to Lorrimer to stop his family’s enemy himself, after Dracula arranges for the kidnap of Jessica. It’s Cushing who really holds this together. Like most attempts at creating something hip ‘n’ happening, when viewed forty years later, it looks incredibly dated, with the fashions, hair, cars, etc. presented here, no more than a sniggerworthy distraction. However, when the film is not irrevocably located in 1972, it’s much better, with Beacham a decent damsel in distress, and Neame enjoyably loopy as the Renfield character – we can only presume Malcolm McDowell was unable for the part.

Credit also to Michael Coles’ Inspector Murray: he’s the main target of disbelief for Cushing’s explanations, and once again, Cushing sells it so absolutely, you wonder why the entire police force of London is not out there with torches and pitchforks. It’s this seriousness that yanks the film up by the bootstraps and by the end, you’ve forgotten the silliness with which the film arrives in the present-day. It would have been nice to have more of Cushing and Lee facing off, for the first time in the series since the original, but I’ll take what we get here, and am happy enough to do so. B-

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.