The franchise has been a staple of horror since the days of the Universal monsters. But to a certain extent, they’re largely a Hollywood creation. While other countries have made horror films, the concept of five, six or more films in a series isn’t something which you see often. The Japanese do go there, with items like the Tomie franchise, which consisted of nine films (not even including an OAV series) between 1998 and 2011. The Mr. Vampire series from Hong Kong has already been covered. But I’m hard pushed to think of many other genuine cases from overseas that go past a trilogy. Even in Italy, though La Casa has reached #7, these are mostly cash-in renamings of entries in the Evil Dead and House franchises, rather than original titles.

There is one exception, and it’s an unexpected one: Turkey. Which is interesting, because prior to the 21st century, there was not really a significant horror genre there. While there had been occasional entries, beginning with the now lost Çiglik (Scream) in 1949, these were more likely to be the subject of derision rather than acclaim. The most well-known is likely 1974’s Şeytan, a wholesale rip-off referred to in the West as “Turkish Exorcist“. Otherwise, pickings are sparse, for reasons ranging from a lack of source material in Turkish literature, to a feeling local audiences would not want to see horror movies.

‘The basis of fear lies not in demons but the wrath of God’ — Alper Mestçi

Around 2004, however, things began to change. That year saw the release of horror-comedy Okul (The School), and also more straightforward horror Büyü (Magic). These helped open the door to horror, and 2006’s Dabbe was the first to use the topic of djinn, and also brought in a Japanese influence, that being where director Hasan Karacadag had worked prior to making his low-budget feature (Dabbe‘s budget was around $160,000). Its success led to five sequels over the next decade, and made Karacadag one of the leading names in the new wave of Turkish horror, alongside Özgür Bakar and Alper Mestçi. But just as Blair Witch spawned a hundred inferior copycats, so the success of Dabbe led to others trying to reproduce it.

By 2022, it was estimated that 60 Turkish horror films were released to theatres there, but many of these were super cheap, and this is reflected in their production values. one critic saying “They are shot in a few days, the equipment is poor, and the film can come out blurry.” But at the other end, if you are only familiar with nonsense like Turkish Exorcist, you will be surprised by how decent the Siccin series from Alper Mestçi looks, being every bit a match for mainstream horror out of Hollywood. But it also strongly reflects local culture. In the West, religious horror doesn’t do well these days – The Last Omen‘s lacklustre performance the most recent example. But in Turkey, it’s almost the only kind of horror made.

‘Turkey has an audience problem, not a horror movie problem.’ — Alper Mestçi

This is something of which Mestçi is aware, saying, “If 20 horror movies are released in a year, we see similar stories in 19 of them… people who love the horror genre know every movie. That’s why you can’t take a scene from any movie and put it in your own movie.” But he is also aware of the need to operate within what the local audience wants: “Turkish people do not like to watch things they do not believe in.” However, that restricts the available subjects, the director lamenting, “Turkey has an audience problem, not a horror movie problem. We have very few topics we can cover for the horror genre. Killer, vampire, zombie, alien – none of these work in Turkey.”

There is one benefit, in that belief in the subject matter is largely “baked in” to the audience. In the West, the crowd who see horror movies will typically be a secular one, who first need to be brought on board with the premise. While the Turkish state is officially secular, the population are almost entirely Muslim, with faith a much more significant part of society than in Western Europe or America. Here, anyone proclaiming their woes are caused by demonic entities would be on a fast track to a padded room. But in Turkey – or, at least, the version of the country depicted in its horror movies – everyone seems to have the friendly neigbourhood exorcist on speed-dial.

Let’s open the door by taking a look at the six entries in Mestçi’s Siccin (sometimes called Sijjin) franchise, and see what lurks on the other side. We’ll follow up with the Dabbe (a.k.a. D@bbe) series by Hasan Karacadag in June.

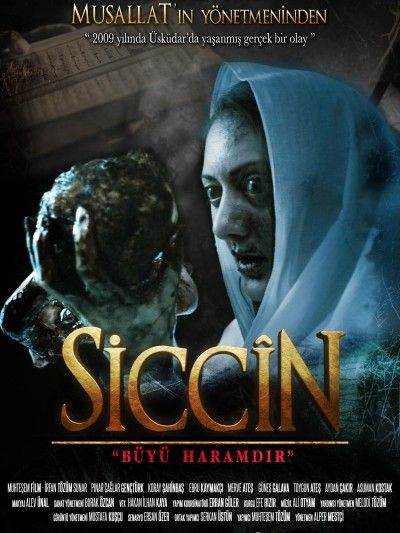

Siccîn (2014)

Rating: C+

Dir: Alper Mestçi

Star: Ebru Kaymakci, Pinar Caglar Genctürk, Koray Sahinbas, Merve Ates

“To be involved with sorcery is one of the biggest sins that mankind could commit, according to Islam.” So proclaims a caption at the end of this, which seems rather disingenuous. Yes, the previous ninety minutes have certainly shown you the downside of meddling with occult forces. But considering this is basically exploiting the topic for movie purposes, it definitely feels like the makers want to have their demonic cake, and eating it too. We begin with Öznur (Kavmakci) visiting a medium and being warned off pursuing a relationship with her cousin, Kudret (Sahinbas). Naturally, she doesn’t listen. 12 years later, Kudret is married to Nisa (Genctürk), but had a brief fling with Öznur – who is now pregnant as a result.

After a fight with the father, Öznur loses the baby, and vows vengeance as a result. This involves more occult shenanigans, which will summon an evil spirit or djinn, to take up residence in Kudret’s household, and wipe out Nisa’s entire bloodline. This does seem a little callous. Sure, Kudret was a bit of a dick, to put it mildly. But why target Nisa, who has no clue about her husband’s infidelity, and worse still, Ceyda (Ates), their blind daughter? I guess the “you cost me my child, so I’m going to take yours” argument applies, but still seems harsh punishment. However, the twisted visions and malevolent results are not limited to them. Öznur is also hallucinating, and it appears the scope of the djinn‘s malevolence is not strictly limited.

First time I’ve seen a film on YouTube which requires you to accept a “The following content may contain suicide or self-harm topics” warning before it’ll play. This presumably refers to the sequence where Nisa tries to hang herself – though I guess it could be where her bedridden mother takes an impromptu shower of scalding soup. I wouldn’t say these were the most disturbing sequences. Pretty much the entire second half consists of a series of djinn-provoked visions experienced by the various characters, in lieu of plot progression. On their own, they are fine, it’s just they demonstrate a diminishing return. Eventually, Kudret finds an imam willing to do the necessary ritual, and we basically go full Exorcist.

First time I’ve seen a film on YouTube which requires you to accept a “The following content may contain suicide or self-harm topics” warning before it’ll play. This presumably refers to the sequence where Nisa tries to hang herself – though I guess it could be where her bedridden mother takes an impromptu shower of scalding soup. I wouldn’t say these were the most disturbing sequences. Pretty much the entire second half consists of a series of djinn-provoked visions experienced by the various characters, in lieu of plot progression. On their own, they are fine, it’s just they demonstrate a diminishing return. Eventually, Kudret finds an imam willing to do the necessary ritual, and we basically go full Exorcist.

If the story runs out of ideas in the middle, I was more impressed by the technical aspects. In particular, the audio work is excellent, with a soundtrack which dials the unsettling sounds up to 11. The components of the actual curse are a bit disturbing too, requiring the sorcerer – apparently accompanied by his aged mother – to dig up a corpse, carve verses from the Koran on its bones, then wrap them in the intestines of a freshly-slaughtered pig (an element not exactly limited to “noises off”). The results prove highly resistant to Muslim anti-magic, leading to a rather abrupt ending, albeit one which definitely acts as a health warning against this kind of thing. And, I imagine, having extra-marital affairs too.

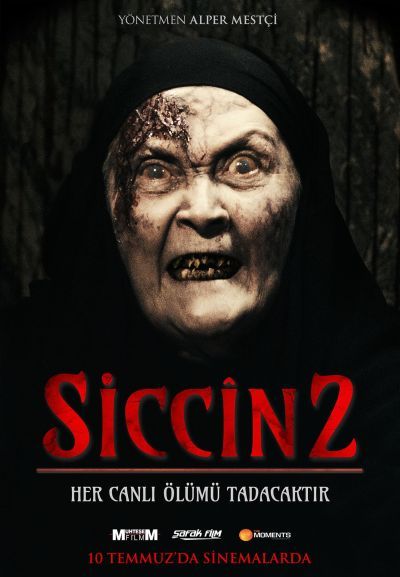

Siccin 2 (2015)

Rating: B

Dir: Alper Mestçi

Star: Seyda Terzioglu, Bulut Akkale, Ece Edibe Baykal, Yavuz Cetin

While the opening credits here play out over a montage of moments from the first film, there’s no other connection. It’s a new scenario, with new characters, though the message remains the same. “Every day, thousands of people in Turkey either cast a spell on someone, or are exposed to a spell,” warns the caption at the end of this one. Remember, folks: only you can prevent occult curses. While that remains at the heart of the story, the structure here is basically reversed. In the first film, we knew from the start who had kicked things off, and for what purpose. Here, that is only explained, almost at the very end, and I think it sustains interest better.

Certainly can’t argue about the start making an impression. Adnan (Terzioglu) and Hicran (Akkale) are a happily married couple, until we see a wardrobe mysteriously topple over and crush their toddler son to death. Yeah, read that sentence twice: Turkish horror movies do not fuck around. This screws both parents up badly, for obvious reasons,. Mother Adnan’s pain in particular, is palpable to an almost awkward degree, and watching her feels voyeuristic. But as things unfold, it becomes clear that this was no accident, and is related to a family feud dating back before her birth, between her mother and her aunt. A lot of blood was spilled, and the ramifications of the dark magic used at the time, still echo down the generations.

It’s mostly Adnan’s story, as she visits her mother and grandmother, and picks away at the scab of some pretty sordid family history. This affects her personally in a huge way, and the way the film finishes reflects this. Without giving too much away, the ending feels very much a “swing for the fences” one, and it may or may not knock it out of the park. That’s likely a subjective assessment, but it worked for me, fitting in with the generally grim tone of proceedings generally. Nothing illustrates that better than Hicran’s fate. He initially seems a bit of a dick, blaming his wife for their son’s death. But it clearly has affected him every bit as much. Again: hard to watch.

It’s mostly Adnan’s story, as she visits her mother and grandmother, and picks away at the scab of some pretty sordid family history. This affects her personally in a huge way, and the way the film finishes reflects this. Without giving too much away, the ending feels very much a “swing for the fences” one, and it may or may not knock it out of the park. That’s likely a subjective assessment, but it worked for me, fitting in with the generally grim tone of proceedings generally. Nothing illustrates that better than Hicran’s fate. He initially seems a bit of a dick, blaming his wife for their son’s death. But it clearly has affected him every bit as much. Again: hard to watch.

If the audio department deserved praise for their work in the first film, here it’s the set dressers I want to single out. The old, abandoned house where all the shit went down, back in the day, is one of the creepiest looking dwellings (top) I’ve seen since The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. It’s a real… fixer-upper, shall we say. Meanwhile, Mestçi loves him a good jump-scare or twenty. Normally, it would be the kind of thing I’d hate, but the director just keeps banging away with them, and it becomes almost endearing. After a somewhat ho-hum opening entry, this certainly delivers its quota of moments you will remember, and I find myself with greater expectations for future chapters from the Book of Sins.

Siccin 3: Forbidden Love (2016)

Rating: B-

Dir: Alper Mestçi

Star: Adnan Koç, Büsra Apaydin, Cem Uslu

The moral is, as usual, made clear by a caption at the end which tells us scholars of Islamic jurisprudence have concluded “It’s inappropriate for jinn and people to marry.” No shit. On the evidence this provides, the conclusion is about as blatantly self-evident, as a Papal edict declaring it’s not recommended for priests to diddle kids. There are a trio of characters at the core here: brother and sister Sedat (Uslu) and Kader (Apaydin), and their friend Orhan (Koç), who ends up marrying Kader. He’s the boss at a factory where Sedat also works, and things go awry after Orhan has to fire an employee for smoking in the flammable work environment.

The smoker, who has a lot of debt, takes poorly to this, committing suicide, and his widow unleashes a curse on Orhan: “I hope you have a dark end.” It doesn’t take long for things to go wrong, with a car accident leading to the death of Kader, and leaving Sedat’s son severely disabled. Orhan is understandably devastated by the loss of his one true love, and resorts to the dark arts to bring Kader back – or, at least, a fairly convincing simulacrum of his late wife. If you have read the first paragraph, you will probably be able to work out how well this works. The ripples of his dabbling in the occult affect Sedat and Kader’s family, over the week which follows.

Matters come to a head after Sedat consults with a hodja. These show up quite often in the franchise, and seem to be somewhere between a psychic and a spiritual adviser. In the series, they’re basically a good way to do exposition dumps, and explain what’s going on. Though here, we don’t really get much of an explanation until the end, despite the fact Sedat is telling the story as a flashback. Interesting that Orhan never explicitly suffers any punishment for his actions. There’s a vague suggestion he might have killed himself at the end to be with Kader again, but it’s definitely not delivering on any sense of moral justice. It does, however, sustain the generally grim, downbeat approach. Happiness is fleeting, if ever experienced.

Matters come to a head after Sedat consults with a hodja. These show up quite often in the franchise, and seem to be somewhere between a psychic and a spiritual adviser. In the series, they’re basically a good way to do exposition dumps, and explain what’s going on. Though here, we don’t really get much of an explanation until the end, despite the fact Sedat is telling the story as a flashback. Interesting that Orhan never explicitly suffers any punishment for his actions. There’s a vague suggestion he might have killed himself at the end to be with Kader again, but it’s definitely not delivering on any sense of moral justice. It does, however, sustain the generally grim, downbeat approach. Happiness is fleeting, if ever experienced.

This runs 20-25 minutes longer than previous installments, and does result in somewhat languid pacing. Nowhere is this chill more obviously demonstrated that when Kader’s mom goes to the bathroom, where she sees the mirror shaking violently, and finds a magic spell placed by Orhan, taped to the back of it. Rather than freaking out, as I probably would, she simply cuts it up with scissors and flushes it down the toilet. This everyday approach to dealing with black magic is something you just don’t see in American or British horror movies. It may not have the same emotional wallop as part two, and I would have welcomed more explanation of Orhan’s actions. Yet it may be the darkest and most oppressive yet, in terms of overall atmosphere.

Siccin 4 (2017)

Rating: B-

Dir: Alper Mestçi

Star: Mirza Metin, Yasemin Kurttekin, Sebahat Adalar, Merve Ates

The fourth entry drops any subtitle, and also takes a slightly different approach. There’s no direct concept of a “curse” here; the lesson to be learned here is simply not meddling in occult practices. The Yilmaz family are almost entirely innocent victims here. The business belonging to its father Halil (Metin) is struggling, forcing them to move into his mother’s house. [Can’t say I’m surprised by its problems, since we never see him doing any actual work at it] His mother became bedridden and almost catatonic after the death of his father, who is buried in the backyard because that is apparently a thing in Turkey. Her needs are tended to by housekeeper Rahime (Adalar).

Meanwhile, son Omer hardly speaks either, after a traumatic incident, while daughter Hilal (Ates) keeps a diary, recording the increasingly unsettling events. Interestingly, Ates also played a role in the first franchise entry, though her character here is a different one. I’m wondering if Mestçi is going for an American Horror Story troupe, or if there are just a limited number of candidates. Other elements here feel almost Fulci-esque, such as the mysteriously locked boiler-room, or the charms and wards Omer finds behind an electrical socket. For it turns out, the house had become a gateway, through which otherworldly creatures can pass. Rahime knows rather more about the situation than she’s initially willing to admit, waving away the charms with, “I know what they are. I’ll tell you later.” I’d have been, “No. Now…”, but that’s just me apparently.

Turns out Omer is particularly susceptible to these entities: “Some little children have their doors open. They can hear darkness and the other realm without any effort. Yet the danger is, they are weak in that realm of darkness.” Though we have already discovered, everyone in the family starts having their own, very realistic and convincing nightmares, in which Grandpa returns from the his grave in the garden, for example. These give Mestçi the opportunity for his beloved jump scares, which remain fun, even if the audience does realize quite quickly that what’s happening is very likely the stuff of dreams. They’re unquestionably well-executed, and the effects here are effective in generating a sense of rotting decay, pushing its way into our world.

Turns out Omer is particularly susceptible to these entities: “Some little children have their doors open. They can hear darkness and the other realm without any effort. Yet the danger is, they are weak in that realm of darkness.” Though we have already discovered, everyone in the family starts having their own, very realistic and convincing nightmares, in which Grandpa returns from the his grave in the garden, for example. These give Mestçi the opportunity for his beloved jump scares, which remain fun, even if the audience does realize quite quickly that what’s happening is very likely the stuff of dreams. They’re unquestionably well-executed, and the effects here are effective in generating a sense of rotting decay, pushing its way into our world.

Things get more complicated after Halil discovers that the spirits are capable of imitating perfectly the inhabitants of the house, though like Omer’s sensitivity, this is an angle which doesn’t receive the exploration it deserves. The ending feels a little confusing and stretched credibility somewhat too, with Halil suddenly turning into Father Merrin and carrying out an exorcism. I dunno, maybe that business of his was countering demonic possessions? Turns out all you need to do to vanquish evil is yell faith-based epithets at the ifrits, along the line of “Nothing will happen but God’s will!”, which leaves the spirits feeling kinda weedy in the final analysis. But up until that point, this has been another creepy and worthwhile entry in the series.

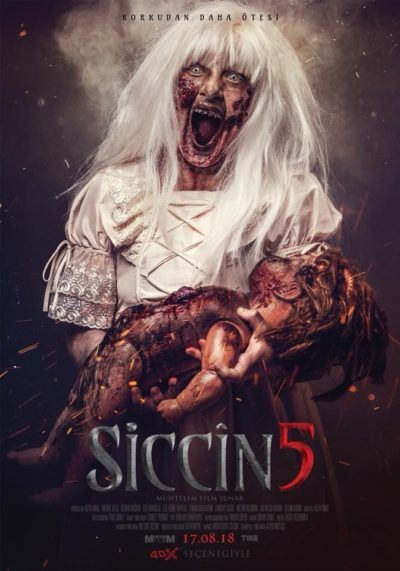

Siccin 5 (2018)

Rating: C

Dir: Alper Mestçi

Star: Rüya Önal, Merve Ates, Özgür Hacier, Ece Koroglu

Is it possible to make a horror film without a plot, consisting entirely of nightmares and jump scares? That appears to be the challenge Mestçi set for himself in making this entry. But it seems like the film-makers were so preoccupied with whether they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should. The previous films in the series, which certainly having their share of hallucinations and shocks, typically did so against the background of a decent story, which held things together. This works something like the first, where you only discover the truth of the situation right at the end, and here, it feels rushed, to the point of coming across as little more than an afterthought.

It does have an interesting set-up. An opening caption tells us, “The Karain village of Nevþehir is known as Cancer Village. Research has shown that the biggest reason the villagers of Karain get cancer is the soil in the region… This film was shot in the Karain village where those cancer cases were seen.” This is more or less true. It’s actually Tuzköy, a town near Nevþehir plagued by early deaths, which was initially thought by locals to be some kind of curse. It was eventually found to be due to erionite, a naturally occurring asbestos-like mineral that, similarly, can cause mesothelioma (there are deposits of it here in Arizona). The entire village was relocated as a result, leaving behind a potentially eerie location. Except it never feels Mestçi takes much advantage of this.

Cynically, this could be described as the story of a house full of hysterical women. There are three generations, all of whom seem to have major mental issues, beginning with the youngest, Hale played by Ates in her third franchise appearance. Though here, she is sporting a platinum blonde wig, which is as unconvincing as it is distracting. She seems to be possessed, holding lengthy, Gollum-like conversations with herself, while torturing a doll. In the house are her mother, aunt Azra (Önal), and grandmother, but her father vanished from the picture years ago. Azra is the only semi-stable one, holding down a job in a shop and a relationship with its owner, Selim (Hacier). Let’s see how long that sanity lasts under pressure, shall we?

Cynically, this could be described as the story of a house full of hysterical women. There are three generations, all of whom seem to have major mental issues, beginning with the youngest, Hale played by Ates in her third franchise appearance. Though here, she is sporting a platinum blonde wig, which is as unconvincing as it is distracting. She seems to be possessed, holding lengthy, Gollum-like conversations with herself, while torturing a doll. In the house are her mother, aunt Azra (Önal), and grandmother, but her father vanished from the picture years ago. Azra is the only semi-stable one, holding down a job in a shop and a relationship with its owner, Selim (Hacier). Let’s see how long that sanity lasts under pressure, shall we?

What you basically get is a solid hour of largely unexplained sequences of dreams and visions, inevitably of an unpleasant and/or harrowing nature. I’m certainly not going to knock the technical elements here. Mestçi could knock this kind of thing out in his sleep; the problem here is, it feels like that’s exactly what he did. It’s all by-the-numbers and gradually diminishes in impact, to the point it becomes hardly more than cinematic noise. When you eventually find out the cause, it’s actually solid, and the subsequent finale (top) is genuinely shocking. Shame this didn’t show up much earlier, as it might have given us something to care about.

Cracking poster though.

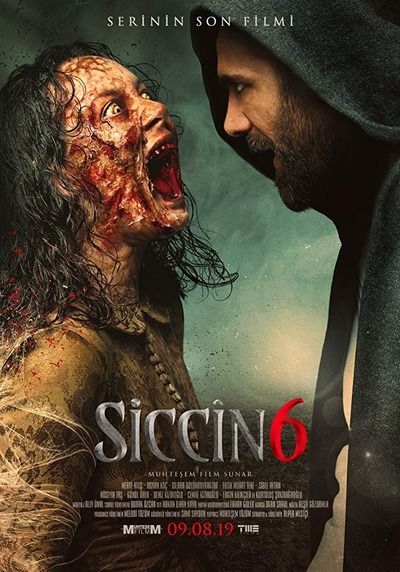

Siccin 6 (2019)

Rating: B

Dir: Alper Mestçi

Star: Merve Ates, Adnan Koç, Fatih Murat Teke, Sibel Aytan

After the disappointing fifth entry, this is a real return to form, breathing fresh life into the franchise. What’s interesting, is that unlike the previous films which were all entirely standalone, this is tied quite closely to Siccin 3: Forbidden Love. There, Orhan (Koç) summoned an ifrit to replace his dead wife. It did not go well. However, he did at least survive, and returns here, sadder, wiser and repentant for his sins. This eventually turns him – after the required amounts of soul-searching and theological discussion – into someone best described as the John Wick of exorcists. The way this ends leaves me quite sorry there have not been any further entries in the franchise since.

To get there, he has to help a family where it seems every member has issues. And when I say “issues”, I mean trauma-based psychological problems, which manifest themselves – you will not be at all surprised to hear – in spectacular nightmares and hallucinations. For instance, Grandpa has guilt over a failed euthanization attempt on his wife, during her painful terminal illness. Auntie Canan (Aytan) is tormented by her inability to have children. Teenage daughter Efsun (Ates, in her fourth entry, and mercifully without the white wig this time) thinks she is possessed by an evil spirit. It’s not just the women. Dad Yasar (Teke) keeps cracking up at work, with old crones gleefully telling him, “I’m haunting your daughter because of your wife.”

Yeah, there are a slew of jump scares and dream sequences, but the execution of these is generally so good, they still work despite being less than subtle. Some of the imagery here is really good, such as where Yasar gets lost in an ever-changing maze of crates. But the finest is where the aunt is menaced by an army of blood-drenched creepy dolls, taunting her in unison as they crawl toward her (top): “You are not going to have children, Canan”. It’s one of the most striking scenes I’ve seen in a horror movie in the past five years. It helps that the performances are all good. I want to highlight Kurtuluş Şakirağaoğlu as Orhan’s spiritual advisor, who delivers difficult dialogue in a compelling fashion.

Yeah, there are a slew of jump scares and dream sequences, but the execution of these is generally so good, they still work despite being less than subtle. Some of the imagery here is really good, such as where Yasar gets lost in an ever-changing maze of crates. But the finest is where the aunt is menaced by an army of blood-drenched creepy dolls, taunting her in unison as they crawl toward her (top): “You are not going to have children, Canan”. It’s one of the most striking scenes I’ve seen in a horror movie in the past five years. It helps that the performances are all good. I want to highlight Kurtuluş Şakirağaoğlu as Orhan’s spiritual advisor, who delivers difficult dialogue in a compelling fashion.

However, the film belongs to Ates, in what might be the best depiction of a conflicted teenager this side of The Exorcist. She manages to be sympathetic: when she sits down beside Yasar and tells him “I don’t want you to die,” it’s entirely convincing. However, she also has the capacity to make Efsun a credible terrifying entity when necessary. It’s rare to see an actor, of any age, able to operate on both ends of the spectrum. By the point Orhan shows up, and the two halves of the plot here finally link up, we are more than ready for a final showdown, pitting good against evil. What we get should prove satisfying to most viewers. If this is the end of the franchise, it’s a solid way to bow out.