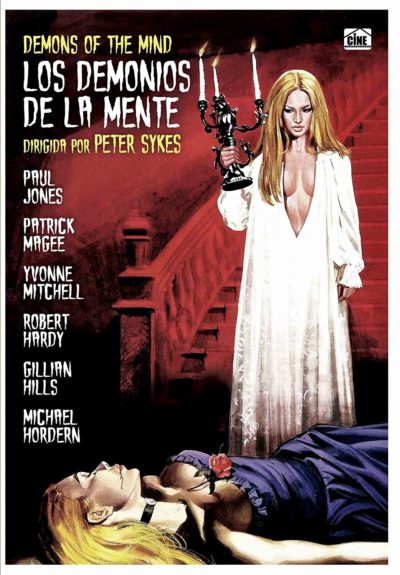

Rating: C-

Dir: Peter Sykes

Star: Robert Hardy, Patrick Magee, Yvonne Mitchell, Michael Hordern

This was originally intended to be Hammer’s second foray into the werewolf genre, coming more than a decade after The Curse of the Werewolf. You can tell, as a number of elements remain, even if the explanation here is more psychological than… hairy. It’s the story of the Zorn family, under Baron Friedrich (Hardy). He is a troubled man, whose wife committed suicide, and he’s concerned that their children, Emil and Elizabeth, have inherited his mental issues. He brings in Doctor Falkenberg (Magee), a physician at the cutting edge of 19th-century medical thinking, to try and cure them. But matters are complicated by a number of factors. A string of murders in the woods. Emil and Elizabeth’s inappropriate feelings for each other. And the arrival of a mendicant priest (Hordern), who is whipping up the village inhabitants into a frenzy over the family’s activities.

Five minutes in, Chris turned to me and said, “This is a very strange film,” and she is not wrong. At times, it feels like everybody in this film is insane. The first time we meet the Baron, he’s quoting the 38th Psalm one of the more sordid passages in the Bible: “My wounds stink and are corrupt. I am brought into so great a trouble and misery, that I go mourning all day long. For my loins are filled with a sore disease and there is no whole part in my body.” That sets the tone for his character admirably. While it’s laudable that he’s so deeply committed to the welfare of his children, the ways in which he shows this are problematic, to put it mildly.

Elizabeth, in particular, is largely reduced to catatonia, even though the question of whether there is anything objectively “wrong” with her, is never answered. Her problems are in part because of the regular bleedings inflicted on her by Aunt Hilda (Mitchell), her effective foster mother, though also an enabler of the Baron’s well intentioned cruelty. Meanwhile, Dr. Falkenberg – based on Anton Mesmer – is as much quack as physician, with some of his ideas being rather questionable, to put it mildly. For example, getting a bit of village totty to pretend to be Elizabeth, in order to fool Emil? What could possibly go wrong? Yeah, I think it’s safe to say, we saw that coming.

Elizabeth, in particular, is largely reduced to catatonia, even though the question of whether there is anything objectively “wrong” with her, is never answered. Her problems are in part because of the regular bleedings inflicted on her by Aunt Hilda (Mitchell), her effective foster mother, though also an enabler of the Baron’s well intentioned cruelty. Meanwhile, Dr. Falkenberg – based on Anton Mesmer – is as much quack as physician, with some of his ideas being rather questionable, to put it mildly. For example, getting a bit of village totty to pretend to be Elizabeth, in order to fool Emil? What could possibly go wrong? Yeah, I think it’s safe to say, we saw that coming.

Even the villagers are a powder-keg of religious fruitcakery, waiting to explode, and the nomadic priest provides the necessary spark. They are first seen collectively, carrying out some kind of bizarre ceremony, which involves burning an effigy which looks like Jack Skellington, while chanting phrases such as “We carry death to the fires of hell!” I’m fairly sure that isn’t something taken from the King James Bible. About the closest the film has to a sympathetic or sane character is Carl Richter, played by Paul Jones, previously the lead singer of Manfred Mann (and almost a member of the Rolling Stones). Carl had become Gillian’s lover after she had escaped from the sanitorium where she had been confined. He follows her back to the Zorn family home, in the hope of being re-united with her. However, he’s very much kept on the sidelines.

This is just a very difficult film to like. You can understand why UK distributors EMI, apparently had no real idea of what to do with it, and sat the movie on the shelf for a while. The character of Emil is credited as “introducing Shane Briant,” even though he had a starring role in Straight on Till Morning (1972), which was released four months earlier in the UK. EMI ended up burying it on a double-bill with a non-Hammer feature, Tower of Evil, where by most accounts, it flopped. Maybe if they’d kept the werewolf theme, original title (Blood Will Have Blood, a quote from Macbeth), or secured their original cast? Elizabeth was intended to be played by Marianne Faithful, and the studio wanted Paul Scofield or Dirk Bogarde to play the baron, before settling on Hardy.

If you are a fan of A Clockwork Orange, released the previous year, you may recognize a number of the actors here. Magee is most obvious, having played Mr. Alexander in Orange. However, Elizabeth is Gillian Hills, one of the girls in the sped-up threesome enjoyed by Alex, while the local girl who imitates Elizabeth for “therapeutic” purposes (top) is Victoria Weatherall, the woman brought on stage to test Alex during the exhibition of his conditioning. Finally, Alex’s mom, Sheila Raynor, plays here what the credits call an “Old Crone”, and Jan Adair had bit parts in both movies. The overlap makes sense when I found out the two films had the same casting director, James Liggat.

However, Magee and Hardy appear to be engaged in some kind of over-acting contest, though there is a degree of justification for both in their characters. The Baron is teetering on the edge of hysteria, regarding both his own mental condition and that of his children. A certain degree of highly-strung nervousness is perhaps to be expected. Falkenberg, meanwhile, is as much showman and medical practitioner, and so delivers his lines with a highly theatrical flair. Regardless of justification, it all does get terribly wearing on the audience. The movie seems to spend all its time amped up to eleven, and I yearned for the understated approach of Peter Cushing.

It perhaps is simply trying to cram too much into its eighty-five minutes, with the results needing to bounce around from thread to thread, never developing many of them satisfactorily. The priest and Carl, in particular, seem to get short shrift, in favour of incestuous canoodlings between Emil and Elizabeth, which I could have survived without. It’s a misfire to be sure; the same cannot be said of the Baron’s rifle at the end. This weapon clearly packs quite a punch, sending its target flying across the air with an enthusiasm which has to be admired. If only the rest of the film possessed anything approach the same focus in its direction.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.