Rating: C+

Dir: Danila Kozlovskiy

Star: Danila Kozlovskiy, Oksana Akinshina, Filipp Avdeev, Nikolay Kozak

a.k.a. Chernobyl 1986

“This film is inspired by real events,” begins this Russian movie – in all honesty, it probably should have continued, “…and by those bastards at HBO who made the Chernobyl disaster into a series first.” I’ve read a lot of reviews slating this for being not so good as the HBO show. If I can’t argue with you there, we should remember these are two independent animals, made for different audiences and purposes, about the same historic event. Oh, this version has its issues, to be sure. However, it admits “the characters and their life stories are fictional.” Any direct comparison is like pitting a documentary about the Titanic against James Cameron’s movie, and complaining that Rose DeWitt Bukater wasn’t on the ship’s manifest.

For example, this doesn’t care at all about the cause. We barely see Chernobyl before it blows up, and the movie’s apathy is explicitly addressed in this exchange between two of the “Liquidators”. They’re the people who worked in perilous conditions to stop the plant from suffering a catastrophic meltdown, which would have imperilled not only Russia, but much of Western Europe:

For example, this doesn’t care at all about the cause. We barely see Chernobyl before it blows up, and the movie’s apathy is explicitly addressed in this exchange between two of the “Liquidators”. They’re the people who worked in perilous conditions to stop the plant from suffering a catastrophic meltdown, which would have imperilled not only Russia, but much of Western Europe:

– Why did this thing really blow up?

– Because of people.

– Which people exactly?

– Does it matter?

That’s the approach this takes. Similarly, the government cover-up is merely hinted at: relatives kept away from the facility handling radiation victims, or cheerful television footage of Kiev festivals, instead of coverage of the incident. This is just one guy’s story: firefighter Alexey Karpushin (Kozlovskiy), who was on the edge of leaving for Kiev, when hell, literally, breaks loose, and he sticks around to fight the catastrophe.

The weakest aspect of this is likely the attempt to shoehorn in a romance with old flame, Olga Savostina (Akinshina) and her son, whom he suddenly discovers is hers. This is clichéd stuff, an obvious attempt to give the story emotional heart which doesn’t work, even when the kid looses his hair and looks mournful. It’s on much more solid footing when pitting Alexey and his colleagues against the reactor. A first trip to the roof is bad enough (if short of the one in HBO), sending him to the hospital. After his release, he goes back to help, his knowledge of the plant proving critical in releasing the water beneath, which will otherwise become irradiated steam.

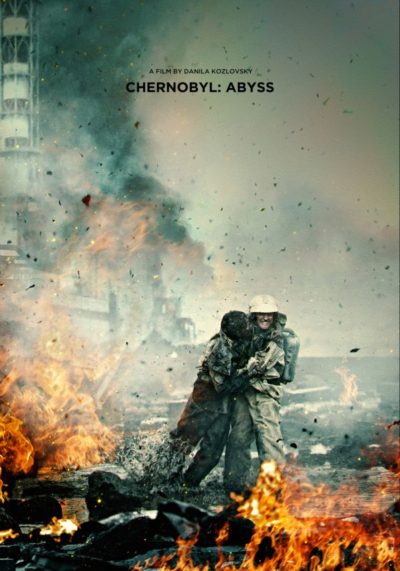

Their exploration of the corridors – not once, but twice – is truly a descent into the inferno, as they plough through near-boiling water and encounter the molten core itself (above). It’s a world of unimaginable lethality, into which no-one should ever have to go. You may not come away from this knowing about the political shenanigans, that both led to, and concealed, the disaster. Yet, again: they’re not the point here. This is s simpler story, one which admittedly may border on Soviet-era propaganda in its portrayal of a rugged hero, prepared to sacrifice everything for the mother state. I can’t find it in myself to discard it purely for that, given its reasonable effectiveness on those terms.