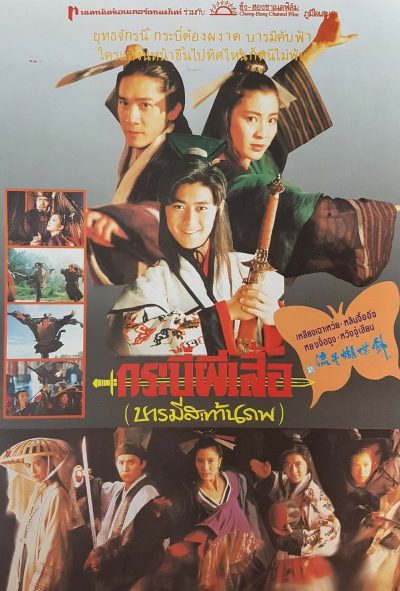

Rating: C+

Dir: Michael Mak

Star: Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, Michelle Yeoh, Joey Wong, Donnie Yen

I’m not sure how it took me twenty-five years to get round to seeing a film starring both Yeoh and Yen, two of my favourite Hong Kong action stars. It certainly has everything I love about the wuxia genre of flying fantasy. In just the first five minutes, we get shurikens outfitted with gyroscopic stabilizers, bodies that explode on contact, and Meng Sing Wan (Leung) using his bow to fire both his sword and himself at the enemy. The former, from behind his back, because… Reasons. Unfortunately, it also has everything I hate about the wuxia genre of flying fantasy, in particular a plot which is nonsense when it isn’t busy being entirely incomprehensible. Maybe the opening narration, which they apparently couldn’t be bothered to subtitled, explained things. Or perhaps the book on which this is based?

As best as I can tell. Meng is part of the awkwardly-named assassins’ guild Happy Forest, led by Sister Ko (Yeoh), but keeps his day job hidden from his girlfriend, Butterfly (Wang). Ko gets a mission to steal a letter from rival guild Elites Villa, and Meng is dispatched to go undercover there, after faking his own death. But off on the side, there’s a love polygon going on. Ko has a whole unrequited affection thing going on for the oblivious Meng, in shades of Crouching Tiger. But she in turn is loved by another Happy Forest member, Yip Cheung (Yen). And while on his mission, Meng stumbles across the spitting image of his first love, who vanished a decade ago. Cue much wistful gazing.

As best as I can tell. Meng is part of the awkwardly-named assassins’ guild Happy Forest, led by Sister Ko (Yeoh), but keeps his day job hidden from his girlfriend, Butterfly (Wang). Ko gets a mission to steal a letter from rival guild Elites Villa, and Meng is dispatched to go undercover there, after faking his own death. But off on the side, there’s a love polygon going on. Ko has a whole unrequited affection thing going on for the oblivious Meng, in shades of Crouching Tiger. But she in turn is loved by another Happy Forest member, Yip Cheung (Yen). And while on his mission, Meng stumbles across the spitting image of his first love, who vanished a decade ago. Cue much wistful gazing.

Wuxia is a weird genre, where the line between genius and insanity is a thin one. Why does this stumble, when something like the same year’s Flying Dagger succeeds? How much is too much? Hard to say – though like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, I know it when I see it. Outside of the OTT action, what works here are mostly the little things. There’s a delightful sequence flashing back to Ko and Meng as kids, depicting the origins of the Happy Forest, which could have become a fun movie on its own. Or there’s the letter Meng leaves for Butterfly before one of his departures, whose quirkiness is exceeded only by its length.

These moments succeed, when the bigger plot threads seem to be rushed past so quickly, they make no impression. It’s all just too hyper to have an impact on more than a subliminal level. For large parts, you can’t really see what’s happening, it just enters your brain in a fire-hose of imagery: before you have time to process it, the film has already galloped on, and is hurling something else at you, typically in even greater defiance of the laws of physics. That prevents the action from creating any kind of connection on an emotional level, and leaves you with an experience which you may remember, yet is none the less empty for it.