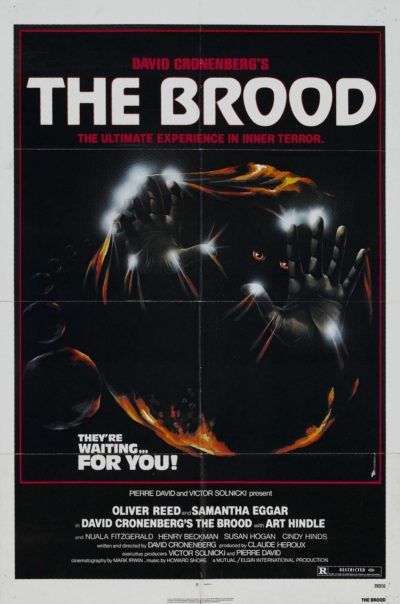

Rating: B-

Dir: David Cronenberg

Star: Oliver Reed, Samantha Eggar, Art Hindle, Cindy Hinds

Just as Roman Polanski dominated the late sixties section of this feature, so Cronenberg dominates this period. There’d be more from him, if I wasn’t such a fanboy and so had covered things like The Fly and Videodrome before. He had already found his feet in the body-horror genre, with Shivers and Rabid, but then made an deviation back to more normal fare. March 1979 also saw the release of auto-racing movie, Fast Company, starring William Smith, Claudia Jennings (in her final role, before being killed, ironically in a car accident) and John Saxon, It was the first feature directed by Cronenberg for which he did not write the screenplay, though his love of cars make this less of an aberration than it might initially appear.

Two and a half months later, normal service was resumed in no uncertain terms with The Brood, which Cronenberg famously described as “My version of Kramer vs. Kramer – but more realistic.” The director was going through a nasty divorce from his first wife, Margaret, leading to a custody battle over their daughter, Cassandra, and if you read the film in this light, it takes on a different, considerably more personal, tone. Eggar’s character, Nola Carveth, was based on Cronenberg’s wife, and it’s not much of a stretch to see the man himself in the combined roles of her husband, Frank (Hindle) – perhaps representing Cronenberg’s emotional side – and psychotherapist Dr. Hal Raglan (Reed) as the more dispassionate, analytical part of his character.

The problem is, I now want to read every other film in the Cronenberg filmography similarly, as a metaphor for some traumatic incident or other in his personal life. Videodrome was about an appointment with an optometrist where David was displeased with the service. Shivers followed a disappointing stay in a B&B. And Scanners was inspired by a really bad headache. Hey, I’m not going to complain. From 1975 through 1988, we had arguably the greatest period of output by a single horror director in the history of cinema. Some might argue for Dario Argento’s or George A. Romero’s production, over a roughly similar period (damn, the early eighties were a totally golden age for the genre). But to me, Cronenberg’s was near-perfect, showing that horror could be smart, without giving up its extreme edge.

The problem is, I now want to read every other film in the Cronenberg filmography similarly, as a metaphor for some traumatic incident or other in his personal life. Videodrome was about an appointment with an optometrist where David was displeased with the service. Shivers followed a disappointing stay in a B&B. And Scanners was inspired by a really bad headache. Hey, I’m not going to complain. From 1975 through 1988, we had arguably the greatest period of output by a single horror director in the history of cinema. Some might argue for Dario Argento’s or George A. Romero’s production, over a roughly similar period (damn, the early eighties were a totally golden age for the genre). But to me, Cronenberg’s was near-perfect, showing that horror could be smart, without giving up its extreme edge.

That said, I feel this may be the least effective of Cronenberg’s early work, albeit only relatively. It’s the dispiriting family drama which drags the overall movie down. There is a reason, after all, he did not direct Kramer vs. Kramer. It centres on Dr. Raglan’s therapeutic practice of “psychoplasmics,” carried out at the Somafree Institute. This gets patients to exercise their past traumas in ways that manifest themselves in physical ways like weals on their skin. His leading subject is Nola, who has been living at the Institute for a while. Her husband, Frank, is concerned to discover marks on the body of their six-year-old daughter, Candace (Hinds, seeming like a predecessor to Heather O’Rourke), after she visited her mother. Worse is to follow, as those around the Carveth family are subject to murderous attacks by what can only be described as mutant children of unknown origin – the influence of Don’t Look Now on these, cannot be denied.

When two such creatures kidnap Candace from her school, and Raglan sends every patient bar Nola home, Frank decides to pay the Institute a visit. That’s when things really get weird. Even by Cronenberg standards. For it turns out Nola’s abused past has been turning into the mutants. Raglan has been housing them in a dorm, but they have been sliding out to punish those who maltreated their “mother”, or are perceived by her as a threat. I’m not sure what Raglan’s goal is, since – regardless of ethical considerations – turning patients into brood mares for psycho dwarves does not seem like a sustainable business model. It’s not as if Nola appears greatly helped by the treatment, and that’s discounting the multiple deaths of others which are a consequence. “May cause the spontaneous parthenogenesis of mad, hammer-wielding midgets with no navels” is one hell of a side-effect for any therapy.

It does have a serious point to make, about the cycle of trauma, psychological damage and abuse. Nola was broken by her mother’s callous treatment, and the film’s final shot shows that Candace is now likely going down the same route. I actually was concerned about the young actress, who has to go through her share of cinematic hell, such as watching her grandma get blunt instrumented to death. Indeed, her primary 1 classmates see the same fate befalling their teacher: years of therapy beckon. I’m pleased to report Hinds seems to have survived and is now a realtor. Though from a contemporary view, the most shocking thing is Frank taking Polaroid pics of his topless little daughter. These days, if word of that kind of parental activity got out, you’d be lucky if you only lost custody, rather than your freedom.

It does have a serious point to make, about the cycle of trauma, psychological damage and abuse. Nola was broken by her mother’s callous treatment, and the film’s final shot shows that Candace is now likely going down the same route. I actually was concerned about the young actress, who has to go through her share of cinematic hell, such as watching her grandma get blunt instrumented to death. Indeed, her primary 1 classmates see the same fate befalling their teacher: years of therapy beckon. I’m pleased to report Hinds seems to have survived and is now a realtor. Though from a contemporary view, the most shocking thing is Frank taking Polaroid pics of his topless little daughter. These days, if word of that kind of parental activity got out, you’d be lucky if you only lost custody, rather than your freedom.

The other theme is the self-inflicted – at least, for the parents – wounds of an ugly, acrimonious divorce. We never get to see Mr. and Mrs. Carveth in happy times: from the start, it’s a dysfunctional relationship, grinding its way towards an inevitable dissolution. The score, the first for Cronenberg by long-time collaborator Howard Shore, only deepens the abyss of domestic hell. It’s almost as horrific as Nola giving birth to one of her offspring, then licking the new-born clean, like a mother cat – a scene which was among the cuts required for an R-rating. Critics like Derek Malcolm (“Goodness knows how I got through the movie without being sick”) and Roger Ebert (“an el sleazo exploitation film, guaranteed to nauseate you, after it bores you first”) were thoroughly unimpressed by the mix of family drama and body horror. “Are there really people who want to see reprehensible trash like this?” asked Ebert, I guess rhetorically. Not one of Roger’s more well-considered opinions. Safe to say Cronenberg had the last laugh.

This article is part of our October 2022 feature, 31 Days of Classic Horror.