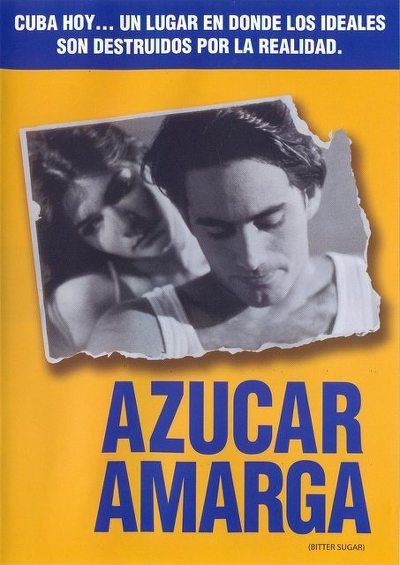

Rating: C+.

Dir: Leon Ichaso.

Star: René Lavan, Mayte Vilan, Larry Villaneuva, Miguel Gutiérrez.

a.k.a. Azúcar Amarga

I’m not sure I’d be too bothered living in a dictatorship. It’s not as I’ve been able to vote for the past 15 years as is, and fuck you, Benjamin Franklin: I will trade a little liberty for security. If it helps stop me being blown up by terrorists, go ahead. Anyone tapping my phone-calls and reading my emails is going to get really bored, very quickly. On the other hand, I have a strong aversion to censorship, which dates back to the “video nasties” days. The more the BBFC told me I shouldn’t get to see something, the more I wanted to. What they should have said was, “Knock yourself out, see how crappy they are. Then you’ll be sorry…” A few viewings of shit like Revenge of the Bogeyman, and I’d have lost all interest.

That isn’t unrelated to this movie, which could easily be filed under “protesting too much”. While set in Cuba, this slice of agitprop was made by disgruntled expats in the Dominican Republic, with the aid of some guerrilla shooting and archive footage from Cuba. It’s about as unsubtle an anti-Communist polemic as has been committed to film since the end of the McCarthy era. I’d perhaps have a different opinion if my relations had been kicked out of Cuba and had all their property seized by the state [thanks to Chris and her family, I do know all about that. She still mutters occasionally about returning to Havana with a jackhammer, and digging up a certain back-patio…]. But instead, the obvious propaganda we get here, tends to push me in the other direction.

That isn’t unrelated to this movie, which could easily be filed under “protesting too much”. While set in Cuba, this slice of agitprop was made by disgruntled expats in the Dominican Republic, with the aid of some guerrilla shooting and archive footage from Cuba. It’s about as unsubtle an anti-Communist polemic as has been committed to film since the end of the McCarthy era. I’d perhaps have a different opinion if my relations had been kicked out of Cuba and had all their property seized by the state [thanks to Chris and her family, I do know all about that. She still mutters occasionally about returning to Havana with a jackhammer, and digging up a certain back-patio…]. But instead, the obvious propaganda we get here, tends to push me in the other direction.

Young engineering student Gustavo (Lavan) is still a true believer in the revolution and Castro, and is excited to have won a scholarship to study in Prague. At an illegal concert where the band of his brother, Bobby (Villaneuva), is performing, he meets the very lovely Yolanda (Vilan). The two begin their relationship, but various incidents cause Gustavo to lose his rose-tinted sunglasses and see the regime for the corrupt failure it is. Indeed, Fidel Castro personally comes round to his house to destroy every single thing that is good, including Bobby and Gustavo’s father (Gutiérrez), and takes from Gustavo all he holds dear. Or maybe it just feels like that.

This is certainly a case where less would have been more. Perhaps concentrate entirely on the Gustavo-Yolanda thread, which is drawn out and developed in a nicely credible way, with a couple of good lead performances. Or even just reining in some of the more eyebrow-raising elements, such as how Bobby and his fellow band-members decide to protest their suppression. Their protest, involving AIDS-infected blood, is certainly memorable, yet you don’t get enough sense of why – what would drive someone to such an extreme response? This inexplicably flamboyant grandstanding takes away from the generally relatable nature of the other characters.

It is much more effective when not doing the cinematic equivalent of yelling in your face, and simply depicting the struggles of everyday life. For example, at the graduation party for Gustavo, his father brings out a cake, and dryly calls it “a monument to Socialism,” because the ingredients were obtained through barter and exchange: “Pepe traded a used light bulb for a little flour. Jaime donated a little can of American Quik which his brother brought him from Miami when he visited. I found hidden on a kitchen shelf, a little bottle of vanilla extract dated 1960. So, if you get a stomach ache, it’s not my fault!” Shame there’s not more of this, for in 20 seconds, the scene does a better job of showing the problems with the current regime than the overblown finale eventually reached.