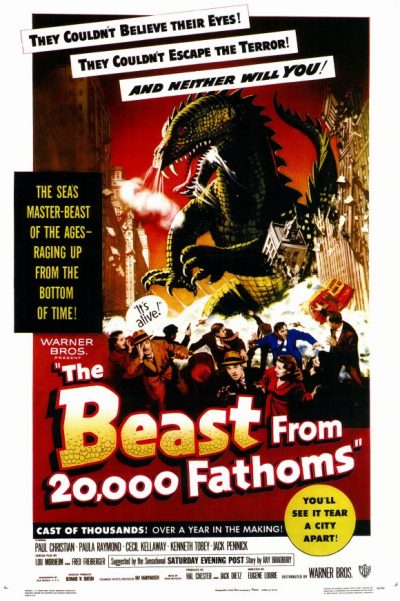

Rating: C+

Dir: Eugène Lourié

Star: Paul Christian, Paula Raymond, Cecil Kellaway, Kenneth Tobey

I was a bit surprised when I saw the creature in this one, because it was a) a giant lizard, and b) attacking New York. Wasn’t the beast actually a giant octopus, attacking San Francisco? Turns out, no: I was confusing it with the one out of It Came From Beneath the Sea, released two years later – though some confusion is understandable, since both feature stop-motion work by Ray Harryhausen. Beast is actually among the very first of the post-war, atomic, “giant monster” films, pre-dating both the first Godzilla film and Them! But even at this early stage in the genre, the basis principles are well-established.

A nuclear test in the Arctic unleashes a deep-frozen creature from the Cretaceous era, the Rhedosaurus. The only person who sees it and lives to tell the tale, is physicist Thomas Nesbitt (Christian), and no-one will believe his story of a 100-foot long monster. After ships begin to vanish between the site of the test and New York, he finds another witness, and succeeds in convincing paleontologist Thurgood Elson (Kellaway) and his attractive assistant, Lee Hunter (Raymond), of the truth. A diving-bell expedition goes horribly wrong, and it’s not long before the streets of Manhattan are being pounded by something very large, carnivorous, and which is effectively impervious to conventional weapons, intent on wreaking havoc, before heading to Coney Island to snack down on the rides, for no readily apparent reason.

A nuclear test in the Arctic unleashes a deep-frozen creature from the Cretaceous era, the Rhedosaurus. The only person who sees it and lives to tell the tale, is physicist Thomas Nesbitt (Christian), and no-one will believe his story of a 100-foot long monster. After ships begin to vanish between the site of the test and New York, he finds another witness, and succeeds in convincing paleontologist Thurgood Elson (Kellaway) and his attractive assistant, Lee Hunter (Raymond), of the truth. A diving-bell expedition goes horribly wrong, and it’s not long before the streets of Manhattan are being pounded by something very large, carnivorous, and which is effectively impervious to conventional weapons, intent on wreaking havoc, before heading to Coney Island to snack down on the rides, for no readily apparent reason.

The credits state it was “suggested” by a Ray Bradbury short story, though the title and a sequence where the monster attacks a lighthouse appear to be be about the only overlaps. [And the title is wholly inaccurate, in any case] Reports say the creators had that scene in their draft, and when Bradbury’s story was brought to their attention, they bought the film rights, both to avoid potential litigation, and to use the author’s popularity to boost the film’s profile. But the main strength is less the plot than Harryhausen’s work, which has aged a good deal better than the gender portrayals. Admittedly, some moments of the mayhem are less than convincing; however, the bulk of it is as good as anything you’ll find, pre-Jurassic Park.

There are elements that are perhaps now more inclined to provoke derisive snorts or confusion for modern viewers. The Arctic “chasm” from which Nesbitt has to rescue a stricken colleague is maybe eight feet deep. The diving-bell scene is inexplicably punctuated by some disturbingly mondo footage of a shark attacking and eating an octopus. We were amused by the cop who unloads his revolver at the beast, using the weapon in that typically 50’s way, which involving jerking your arm forward when firing it. The authorities are curiously unable to locate a 30-yard lizard in Manhattan. And, of course, only in New York would a blind man be knocked down and trampled by the stampeding masses, as they try to get out of the way of the beast. I almost expected someone to yell at him, “I’m walkin’ here!”

It must also be said, viewers will need to be patient to get to the good stuff. The creature appears only intermittently for the first hour or more, popping up to over-turn a ship, say, before turning things back over to the humans. In another element that would become standard for the field (remaining true all the way through to the recent Hollywood remake of Godzilla), the people are far less interesting than the monster, with the supposed romantic relationship between Thomas and Lee failing to convince. Matters are not helped by an ending which doesn’t bother to do anything at all, except end. It goes from mayhem to final title about ten seconds after the beast is slain, without so much as a reaction shot of our hero with his arm wrapped protectively around the heroine.

The method of dispatch does offer an interesting twist, in that it’s not so much the creature cannot be killed by conventional weapons, more that doing so would make matters worse. For its blood turns out to be highly toxic, which put me in mind of the line from Alien: “It’s got a wonderful defense mechanism. You don’t dare kill it.” The result demonstrates the ambivalent approach to nuclear materials at the time: they both release the monster, and turn out to be humanity’s salvation, proving to be the means by which the creature can be taken down. [Look up Operation Plowshare if you want more of this duality, a fifties research program which proposed using atomic blasts for peaceful construction purposes.]

Bonus points if, like Chris, you noticed the presence of Lee Van Cleef as the sharpshooter who eventually takes down the creature, firing a radioactive isotope into a wound to slay it. Although there’s something weird about him and his spotter colleague, riding the roller-coaster up to get a clean shot in their protective clothing – it looks more as if the KKK went on a day-trip to Coney Island. [On the topic of eventually famous people in small roles here, the radar operator, Charlie, is played by James Best, who, a quarter-century later, would achieve fame as Sheriff Rosco P. Coltrane in The Dukes of Hazzard.]

There are cases where ground-breaking films have not stood the test of time particularly well: originality doesn’t necessarily mean you get it right first time. That isn’t the case here, at least, not to any enormous extent. Yes, other films would improve on this film’s weaknesses e.g. Them! does an awful lot better at creating an incredibly creepy atmosphere when the monsters aren’t on screen. However, it’s remarkable to realize how much of what it does, in both characters and plot, is still almost de rigeur for monster movie-makers more than 60 years later.