Rating: C

Dir: Andrew Niccol

Star: Clive Owen, Amanda Seyfried, Colm Feore, Sonya Walger

Niccol got his career started as a feature director with Gattaca, which was a cautionary bit of science-fiction about the potential implications of genetic engineering. 20 years later, he has circled back around, to give us a cautionary bit of science-fiction about the potential implications of privacy loss. And, much like Gattaca, this will provoke not much more than a somewhat-interested “Hmm” – probably before going back to surfing Facebook, and having your personal data syphoned off for sale to some Russian troll-farm. For at the risk of using a comparison roughly 72% of previous reviews have made, the movie plays like a Black Mirror script: just one Charlie Brooker would have rejected as being under-developed.

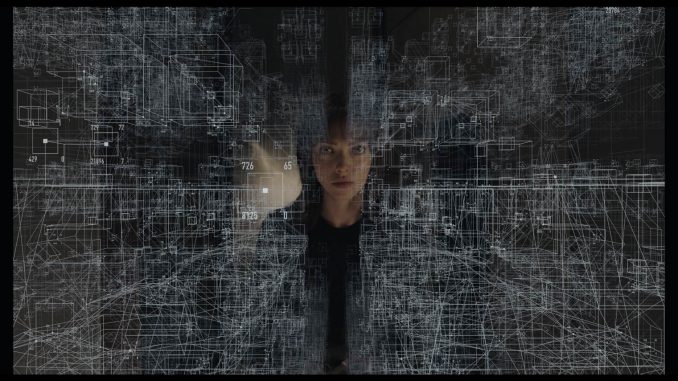

Sal Frieland (Owen) is a cop in a near future where everyone’s experiences become part of their permanent record, which makes policing just this side of piss-easy. You can’t exactly claim you weren’t there, not least because there’s no right to privacy. But a problem has arisen. People are being murdered, and their record shows only the murderer’s perspective, because someone has discovered a way to hack memories. The trail leads to an anonymous girl (Seyfried), who has also wiped herself off the grid entirely. In this universe, when you see someone, you get an immediate overlay with their details, and there’s also a torrent of advertising (very reminiscent of Minority Report) and other information on everyone’s heads-up displays. The girl? “Unknown,” which is what first alerts Sal to her existence.

Sal Frieland (Owen) is a cop in a near future where everyone’s experiences become part of their permanent record, which makes policing just this side of piss-easy. You can’t exactly claim you weren’t there, not least because there’s no right to privacy. But a problem has arisen. People are being murdered, and their record shows only the murderer’s perspective, because someone has discovered a way to hack memories. The trail leads to an anonymous girl (Seyfried), who has also wiped herself off the grid entirely. In this universe, when you see someone, you get an immediate overlay with their details, and there’s also a torrent of advertising (very reminiscent of Minority Report) and other information on everyone’s heads-up displays. The girl? “Unknown,” which is what first alerts Sal to her existence.

This is part of the problem. No real high-level hacker would be so breathtakingly naive as to waive a gigantic red flag like this at the authorities: they’d want to remain as unnoticed as possible. And there’s another major plot-hole. When Sal gets the memories of his dead son wiped as punishment… they’re gone for ever. Has no-one in this universe ever heard of backups? Despite these techno-misfires, there are some occasional moments where it does work, capturing the destabilizing paranoia of a world where, as Sal notes, you literally cannot believe your own eyes. An empty street becomes full of traffic; the train onto which you’re about to step may not be there; enemies become friends and vice-versa.

A full-blown dive down that rabbit-hole could have turned this into a mind-fuck classic. However, Niccol merely makes Sal peer into the abyss, before we get back to the much more pedestrian, and considerably less interesting, topic of finding the murderer. In the end, the “who” of this whodunnit proves forgettable: I would have preferred to learn more about the “how” and the “why”. And perhaps not so much concerning the crime, more the society depicted. As someone who would quite happily trade a large swathe of liberty for security, this didn’t all seem quite as dystopian to me as Niccol perhaps imagines.

Owens is decent value for money as usual, playing a grubbily wrinkled, noir-esque cop, even if it is perhaps a little creepy seeing him make the double-backed aardvark with Seyfried. There just isn’t enough of an emotional connection for this to make its mark, and the potential social ramifications of the technology are almost entirely unexplored.