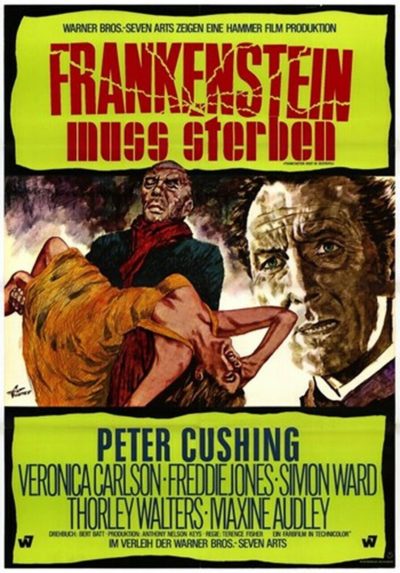

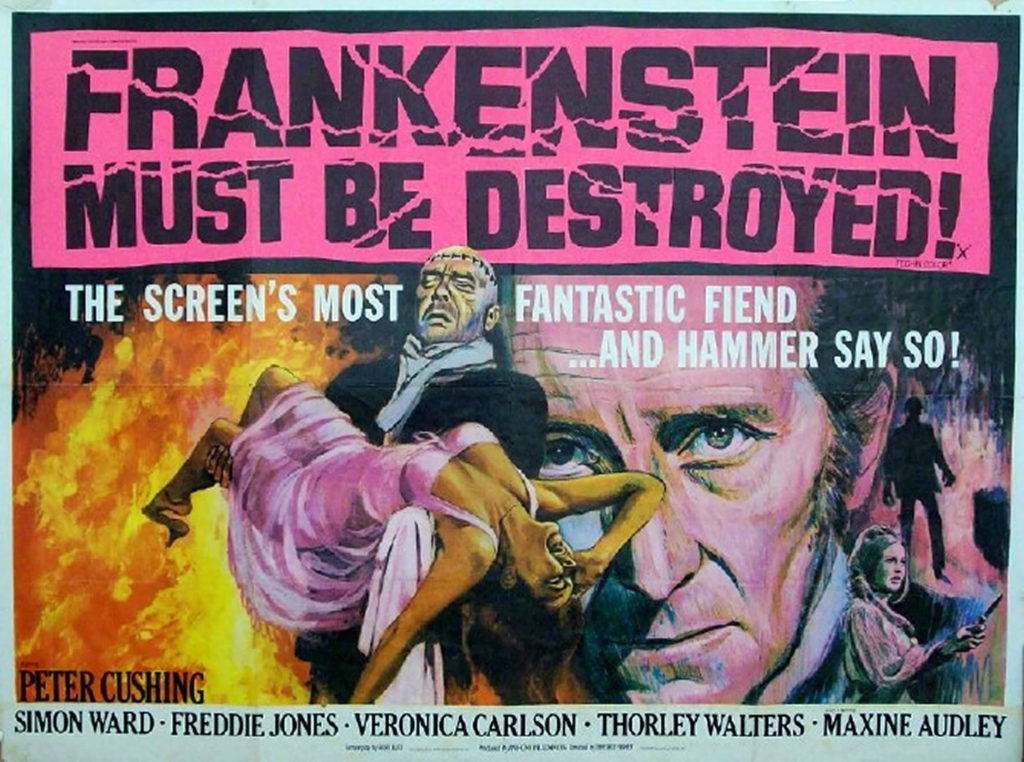

Rating: B-

Dir: Terence Fisher

Star: Peter Cushing, Simon Ward, Veronica Carlson, Thorley Walters

We reach the end of the sixties, and it’s almost as if Hammer took a step back for breath, and to regroup. After releasing five or more films every year over the latter half of the decade, the studio put out just two in 1969 – this and Moon Zero Two. The fallow period, ironically, came on the heels of Hammer being honoured with the Queen’s Award for Industry in May 1968. But I wonder if it also indicates a pause by them, to reflect and adjust. For the previous year had seen a sea-change in genre movies, on both sides of the Atlantic. In the US, Night of the Living Dead redefined horror forever. In the UK, Witchfinder General brought a grim and dark style to its story, with a complete lack of humour. Destroyed feels in part like Hammer’s reaction to the challenge laid down by these iconic competitors.

Certainly, Baron Frankenstein (Cushing) is harsh, abrasive and, in the film’s most controversial scene, more than a bit rapey. Yet part of me still wants to like him on occasion. Such as when Frankenstein tells a group of men gossiping about the doings of scientists, “I didn’t know you were doctors.” When informed they aren’t, he smoothly brings the shade: “I beg your pardon. I thought you knew what you were talking about.” If his sanity is clearly more tenuous in this installment, the Baron’s zero-tolerance policy for idiots remains as consistent as ever. But I think it’s the sharp change in tone that is most apparent here, with precious little light in the darkness – most of it coming from Walters’ investigating police officer, and he feels almost as spliced into proceedings and out of place, as the Baron’s rape scene.

Perhaps the film’s best aspect is the contrast between the Baron and his unwilling little helpers, asylum doctor Karl (Ward) and his girlfriend, Anna (Carlson. fresh off last week’s turn in Dracula has Risen From the Grave). They are by no means spotless, dealing drugs stolen from Karl’s workplace – and discovering this is what gives Frankenstein leverage over them. However, they are doing so purely to raise funds for the medical treatment needed by Anna’s mother. This stands in sharp distinction to the Baron’s crimes, which are carried out for purely selfish reasons, simply because they are a necessary means to his ends. Indeed, even the subject of the brain transplant is considerably more sympathetic than Frankenstein – and for much of the movie is certainly much more law-abiding.

Perhaps the film’s best aspect is the contrast between the Baron and his unwilling little helpers, asylum doctor Karl (Ward) and his girlfriend, Anna (Carlson. fresh off last week’s turn in Dracula has Risen From the Grave). They are by no means spotless, dealing drugs stolen from Karl’s workplace – and discovering this is what gives Frankenstein leverage over them. However, they are doing so purely to raise funds for the medical treatment needed by Anna’s mother. This stands in sharp distinction to the Baron’s crimes, which are carried out for purely selfish reasons, simply because they are a necessary means to his ends. Indeed, even the subject of the brain transplant is considerably more sympathetic than Frankenstein – and for much of the movie is certainly much more law-abiding.

While still with many familiar names, both in front of and behind the camera, there’s something about this that feels different from the Hammer films which had gone before. It’s not as if the studio had jumped the shark – they still had some very solid films to come. But Frankenstein Must be Destroyed appears to be a watershed moment, indicating the new, more explicit direction in which the studio was to head in the seventies.

[November 2010] One of the interesting things about the series is seeing how Baron Frankenstein (Cushing) has evolved through the films. It’s clear that, in the Hammer versions, he’s not just about creating life; if it’s on the frontiers of research for medical science, he’s there – regardless of any pesky questions about “morality”. Informed consent? It’s vastly over-rated… From the soul transference in Created Woman, he has moved on to the notion of brain transplants. He was working with Doctor Brandt on the topic; the latter had made a breakthrough in the process, but had gone mad and been consigned to an asylum before he could pass it on to Frankenstein. By good fortune, the Baron’s landlady, Anna Spengler (Carlson), is betrothed to Doctor Karl Holst (Ward), who works at the hospital where Brandt is incarcerated. When the doctor discovers Karl is also supplying drugs to the black-market, he blackmails the couple, and they are left with no option but to assist in his plan to get the doctor out and cure his insanity. However, injuries received in the process mean the Professor’s body can no longer serve as a vessel…

After the almost avuncular Baron we saw in Woman, he is much less sympathetic here: arrogant, egocentric and completely cold to everyone else. When it looks like he is showing compassion, such as to Brandt’s wife, it is purely for show, with his own purposes foremost in Frankenstein’s mind. There’s even a scene where he forces himself on Anna, which is entirely out of character, and is probably the only time where the Baron shows any interest in sex at all. Neither Cushing nor Carlson wanted the scene, which was added by the producers to keep US distributors happy: that explains why it seems out of place, at least in the context of the overall series, if less so in this individual movie, where the Baron is at his most amoral and least appealing. Conversely, the “creature” is the most intelligent and well-spoken of the films, eloquently expressing to his wife the horror he feels, upon discovering that he is, literally, not the man he used to be.

There are some great moments in the film, perhaps most notably when a broken water-main threatens to expose a dead body previously buried in the back-garden, and a hysterical Anna has to drag it away before they are all caught. However, it never quite gels as well as some other entries: while Cushing was quite capable of playing a villain (as in Twins of Evil), you got the sense he had a moral code. That is completely lacking here, right from the opening sequence in which the Baron engages in a spot of casual decapitation. Cushing seems uncomfortable with the results, and that’s a feeling on which the viewer may pick up. Certainly among the darkest of Hammer’s Gothic offerings, the ending is abrupt, even by Hammer standards. Is Frankenstein destroyed? As ever, the box-office decided the answer… B

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.