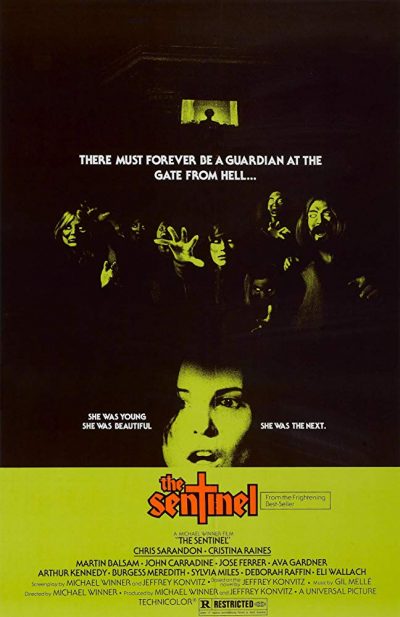

Rating: B-

Dir: Michael Winner

Star: Cristina Raines, Chris Sarandon, Martin Balsam, Burgess Meredith

More or less the last dog-end of the religious horror craze of the seventies, this came out even after To the Devil a Daughter, which helped kill off Hammer Studios. Winner had hit pay dirt three years earlier with Death Wish, though his follow-up, nostalgic cameo-fest Won Ton Ton, the Dog Who Saved Hollywood, was not a success. He sought redemption by adapting Jeffrey Konvitz’s potboiler of the same name, co-writing the screenplay with Konvitz. It’s about as subtle and understated as you would expect from a Rosemary’s Baby knock-off by the director of Death Wish, i.e. operates at the “may contain traces of subtlety” level.

Yet it’s not without its charms, not least a rather stellar cast – or “would go on to become stellar”, at least. For this was a time where Raines would be billed far ahead of Christopher Walken (listed 12th in the end credits, with barely two lines to say), Tom Berenger (18th, in one scene) and Jeff Goldblum (30th, apparently dubbed). Raines plays emotionally fragile fashion model, Alison Parker. She moves into a suspiciously affordable New York apartment, and soon finds herself the subject of increasingly bizarre incidents, such as visits from apartment neighbours who turn out not to exist, being reincarnations of executed murderers. The exception is a creepy blind priest (John Carradine, above) in the attic, who spends his days gazing out of the window.

Yet it’s not without its charms, not least a rather stellar cast – or “would go on to become stellar”, at least. For this was a time where Raines would be billed far ahead of Christopher Walken (listed 12th in the end credits, with barely two lines to say), Tom Berenger (18th, in one scene) and Jeff Goldblum (30th, apparently dubbed). Raines plays emotionally fragile fashion model, Alison Parker. She moves into a suspiciously affordable New York apartment, and soon finds herself the subject of increasingly bizarre incidents, such as visits from apartment neighbours who turn out not to exist, being reincarnations of executed murderers. The exception is a creepy blind priest (John Carradine, above) in the attic, who spends his days gazing out of the window.

I would likely be packing my bags after slicing the nose off the ghost of my dead father, but Alison is apparently made of stronger stuff, despite already having a couple of suicide attempts to her name. I guess, when you get a cheap apartment in the Big Apple, it takes a bit more than hallucinations to make you move out. Give me rent control, or give me… Well, apparently it’s “give me living next to a pair of weird lesbians, one of whom masturbates enthusiastically in lieu of polite conversation.” Turns out, this is an indication the apartment building sits on a gateway to hell, which the priest is guarding, as the latest in a line of ecclesiastical door-men and -women. Alison is next up, something the forces of darkness are keep to prevent, so the gate will be left ajar. Driving her to kill herself would do the trick.

We end up with a finale that sees Alison being chased by a parade of demonic entities. Normally, this would be a chance for a film’s special effects department to shine. Not on a Michael Winner production. “I decided to use real freaks to save hours and hours of prosthetic make up work,” he relates. And that’s how we get the biggest collection of the genuinely deformed, brought together for cinematic purposes since Tod Browning. Winner assures us, “They were all very lovely people and greatly enjoyed being in the film.” Well, that’s alright then. It’s a fitting climax to a movie which is considerably closer to enjoyable than good, yet delivers more than enough warped content across the unholy exploitation trinity of sex, violence and religion.

This article is part of 31 Days of Horror.

Original review: Michael Winner comes in for a lot of flak, but I kinda like the films of his I’ve seen. This is another example, a horror movie with an all-star cast (even the unknowns are all-star: Christopher Walken, Jeff Goldblum and Tom Berenger all get barely-speaking roles. Goldblum, amusingly, even gets dubbed!) which mushes together genuine sideshow mutants, cannibalistic lesbians in leotards and nose violence on zombie fathers, all in an apartment block which just happens to be a gateway to hell. All this and John Carradine as a blind priest – who could want more?

Well, Cristina Raines makes a fine fashion model but her character is way too dumb to be a heroine, staying in her flat long after any sensible person would have run, screaming. Hey, I guess cheap accommodation is hard to find in New York. Sarandon, as her boyfriend, is more pro-active, trying to find out what the hell (hohoho!) is going on, and Meredith is good as a creepily fey neighbour. It swings wildly between understated and excessive, with Albert Whitlock’s effects more than up to the latter. You’re never quite sure whether all the weirdness is just in the heroine’s mind, at least, up until a finale, reminiscent of Tod Browning’s classic horror film, where out come the Freaks. A surprisingly effective mix of schlock and horror. B-