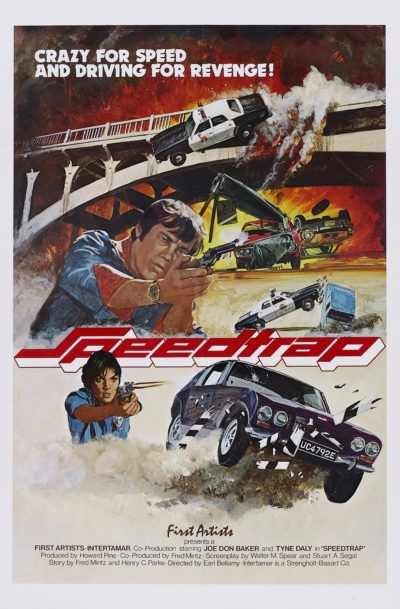

Rating: B-

Dir: Earl Bellamy

Star: Joe Don Baker, Tyne Daly, Richard Jaeckel, Robert Loggia

To be honest, this grade is dependent on being a Phoenix resident. Because a significant part of why I enjoyed this was because it’s a time capsule of the city in the mid-seventies. Arizona was a very different place at that point, the population of Phoenix being just a quarter of what it is now. There have been feature films shot here for over a century (1916’s The Yaqui, now lost, perhaps being the first), but not many contain so much exterior footage as this. Kinda of a necessity, because you can’t really shoot a car-chase film in a studio. And it’s perhaps the other main appeal of the movie: seeing now-vintage cars, whizzing through the local streets.

That said, the cast is solid. We start with Baker, playing private eye Pete Novick. He’s brought in by insurance companies because the police are unable to stop a rash of car thefts. The perpetrator, nicknamed the Roadrunner, has been leading Arizona cops a merry dance, helped by a high-tech gadget that lets them unlock doors and start the engine remotely [real stuff of the future in 1976!]. Novick gets help from policewoman ‘Nifty’ Nolan (Daly, playing a cop four years before Cagney & Lacey), but comes under extra pressure from local crime boss Spillano (Loggia), after the Roadrunner swipes a vehicle with a million dollars of Spillano’s heroin in it. Novick, however, doesn’t have a lot of time for organized criminals.

This is one of the films to follow in the wake of the success enjoyed by Gone in 60 Seconds, which had earned over 200 times its budget at the box-office in 1974. Indeed, in Japan, Speedtrap was released as “New Gone in 60 Seconds”. The movie was not so fortunate in the United Kingdom, where it became the bottom half of a double-bill, paired with… Carry on Emmannuelle. This starts as it means to go on, beginning with a well-staged sequence where the Roadrunner is chased by a police car [the thief’s gadget can also block police radios, preventing them from calling for backup]. This ends in the cop car careering off the Ash Avenue Bridge in Tempe (below), and plummeting to the dry bed of the Salt River beneath.

This is one of the films to follow in the wake of the success enjoyed by Gone in 60 Seconds, which had earned over 200 times its budget at the box-office in 1974. Indeed, in Japan, Speedtrap was released as “New Gone in 60 Seconds”. The movie was not so fortunate in the United Kingdom, where it became the bottom half of a double-bill, paired with… Carry on Emmannuelle. This starts as it means to go on, beginning with a well-staged sequence where the Roadrunner is chased by a police car [the thief’s gadget can also block police radios, preventing them from calling for backup]. This ends in the cop car careering off the Ash Avenue Bridge in Tempe (below), and plummeting to the dry bed of the Salt River beneath.

The bridge, originally built in 1913 by convict labour, had been abandoned for 45 years by that point, being unsuitable for vehicular traffic. It was largely demolished in 1991, though a fragment on the South side still stands. But that does illustrate what I mean about this being a time-capsule. Watching this scene felt like viewing Lumiere Brothers street footage from the turn of the twentieth century, offering a glimpse to a bygone era which has gone forever. There’s also scenes shot in and around Sky Harbor Airport, at Terminal 1. Like the bridge, the terminal was torn down in the early nineties as Phoenix’s population exploded, the location being turned into an economy parking lot. While therefore not recognizable to me, since I first visited the city in 1998, this was still fascinating to see.

It largely stands as a testament to how much the city has changed, with some locations completely unrecognizable. One which hasn’t changed much is Veteran’s Memorial Coliseum, called the fairgrounds here, and through which Novick drives in pursuit of the Roadrunner. Its distinctive, saddle-shaped building is still in use today: just a couple of years ago, I walked along the space beneath the grandstands, through which the cars race, when I went to the Arizona State Fair. But for every scene like that, there are several which have changed so radically, I’ve no sure idea where they were shot. The lack of traffic on the streets is another sharp reminder of the era – though given the film’s high-octane nature, this is perhaps an artificial construct.

Just as in 60 Seconds, the action here is remarkably physical. While there may not be as many vehicles destroyed, the sheer solidity of the vehicles involved undeniably packs a wallop. When seventies cars hit things, they stayed hit. Nowadays, tap a bollard and your front end folds like cheap sheets, but this was very clearly made in the days before crumple zones. They’re a good thing for road fatalities (the per capita death rate in the US is now barely half that of 1977); less so for car chase films. While the content of things like Fast X may be more spectacular, I’d argue it has less of a visceral impact, mostly because of its obviously unreal nature.

Unfortunately, another element Speedtrap shares with 60 Seconds is that it has not much to offer in plot and characters. Although Baker is his usual, affable self, the rest of a good cast are mostly wasted. As well as those mentioned above, there’s also Timothy Carey and B-movie queen Roberta Collins, the latter playing a student driver who keeps crossing paths with the Roadrunner’s chases. Lana Wood plays psychic New Blossom, though only in the American cut. For contractual reasons, the European version had the same character, except called Mira, played by Diane Marchal, who also sings the film’s theme song. Like most of the plot elements, this doesn’t serve much real purpose, and you should be able to figure out the Roadrunner’s identity well before it gets revealed.

Unfortunately, another element Speedtrap shares with 60 Seconds is that it has not much to offer in plot and characters. Although Baker is his usual, affable self, the rest of a good cast are mostly wasted. As well as those mentioned above, there’s also Timothy Carey and B-movie queen Roberta Collins, the latter playing a student driver who keeps crossing paths with the Roadrunner’s chases. Lana Wood plays psychic New Blossom, though only in the American cut. For contractual reasons, the European version had the same character, except called Mira, played by Diane Marchal, who also sings the film’s theme song. Like most of the plot elements, this doesn’t serve much real purpose, and you should be able to figure out the Roadrunner’s identity well before it gets revealed.

If you have no interest in the local scenery, this probably drops a whole grade. Although you’ll still be able to appreciate the action, the story has aged poorly, if it ever seemed good to begin with. For supposed former flames, Baker and Daly have zero romantic chemistry, feeling closer to brother and sister than ex-lovers. None of the faffing around with packages of drugs holds your attention, though the notion of high-level police involvement is an interesting one, albeit under-explored. Despite the presence of some impressive horsepower (from a 1967 Jensen Interceptor Mk1 through a 1973 Chevrolet Corvette Stingray, plus a 1955 Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud), this is the kind of seventies obscurity where you’ll probably watch it, and come away with a better appreciation of why it has largely been forgotten, and never released past VHS.