Rating: C

Dir: Seth Holt

Star: Susan Strasberg, Ronald Lewis, Ann Todd, Christopher Lee

a.k.a. Scream of Fear

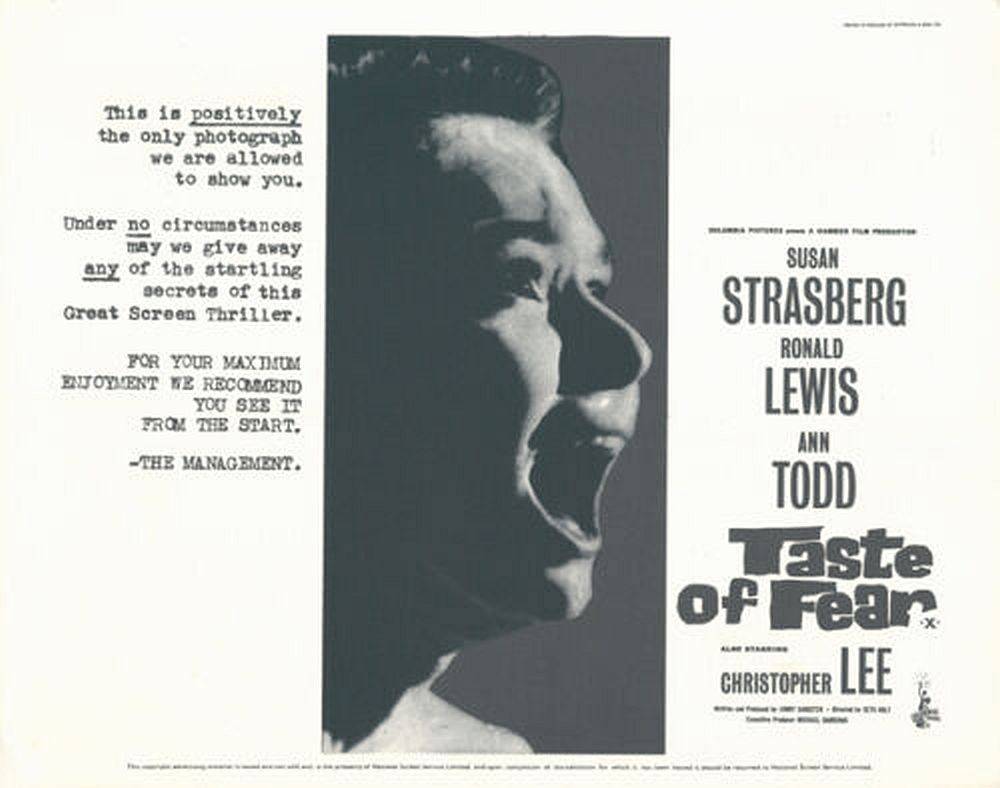

Despite Lee calling this, “The best film that I was in that Hammer ever made,” and writer Jimmy Sangster saying it “has always been his favorite,” I found this rather underwhelming for the first 70 minutes. Perhaps it’s that I’ve seem too many entries in the (rather niche, admittedly) genre of psychological thrillers about plots to drive people mad to claim an inheritance. While the poster (below) is clearly looking to ride on the coat-tails of the previous year’s Psycho, a more direct inspiration here is Les Diaboliques, in which a dead body also won’t stay dead.

This was not originally intended to be a Hammer film, having been first sold by Sangster to Rank, where it was almost produced by Peter Rogers, most famous for his work on the Carry On franchise. Let’s pause for a moment to imagine an alternate version of this, starring Babs Windsor, Sid James, Joan Sims and Bernard Bresslaw in place of the above cast. And moving rapidly on… After it got stuck in development hell, Sangster bought his script back, and Hammer took it on instead. They assigned relatively inexperienced director Seth Holt, then better known as an editor, but paired Holt with experienced cinematographer Douglas Slocombe. He had shot films for Ealing, including Kind Hearts and Coronets and The Lavender Hill Mob, and would go on to be cinematographer on the first three Indiana Jones movies for Stephen Spielberg.

It begins with a body being hauled from the water. I’d recommend humming some Elvis Costello loudly – “She’s filing her nails as they’re dragging the lake” – to distract you from the thoroughly unconvincing matte Swiss mountains in the background. Action then shifts to the south of France, where wheelchair-bound heiress Penny Appleby (Strasberg) arrives at Nice airport, to be met by family chauffeur, Robert. Her parents had split up a decade ago, when she went to be with her mother. But after a series of tragedies – the horse-riding accident that left her crippled, then the death of first her mother, and most recently her companion/nurse – she has come to stay with her father and meet his new wife, Jane (Todd), for the first time. Dad was called away on urgent business, so will not be back for a few days.

It begins with a body being hauled from the water. I’d recommend humming some Elvis Costello loudly – “She’s filing her nails as they’re dragging the lake” – to distract you from the thoroughly unconvincing matte Swiss mountains in the background. Action then shifts to the south of France, where wheelchair-bound heiress Penny Appleby (Strasberg) arrives at Nice airport, to be met by family chauffeur, Robert. Her parents had split up a decade ago, when she went to be with her mother. But after a series of tragedies – the horse-riding accident that left her crippled, then the death of first her mother, and most recently her companion/nurse – she has come to stay with her father and meet his new wife, Jane (Todd), for the first time. Dad was called away on urgent business, so will not be back for a few days.

However, on the first night, Penny is woken in the middle of the night and sees a light on in the nearby summerhouse. Going to investigate, she finds the corpse of her father sitting there. She flees, falling into the pool, from where Robert rescues her. But when the summerhouse is checked, the corpse has vanished and there’s no sign of anything wrong. This is just the first of a series of escalating experiences, such as ghostly piano-playing, which she goes through. Eventually, Penny becomes convinced her step-mother is having an affair with local physician Doctor Gerrard (Lee), and they’re trying to drive her insane. This would let them have her committed and claim an inheritance she’s due to get through a trust fund set up by her grandfather. Together with Robert, she tries to find evidence – such as the dead body – that will let them go to the police. It turns out not to be as simple as that, with virtually no-one being quite who they are pretending to be.

It’s definitely well short of an impeccable plot. For example, when Penny and Robert finally discover what they look for, they opt to load her up into the car and go for a midnight drive to the police station. As Chris immediately pointed out, why didn’t they just call the cops? We know there’s a perfectly good working phone, because Penny spoke to her father on it earlier. And Penny has seen on multiple occasions how things vanish as soon as she turns her back. Of course the reason is, because the rest of the story can only work if the characters don’t do the obvious, logical and sensible thing. Similarly, the ending requires someone to sit in a very particular place in a very particular way, so that a very particular action can occur. We also have a person who continues to pretend to be who they aren’t, even when there’s no-one around to see them do so. [Yeah, I’m manfully struggling to avoid spoilers]

The performances are a bit of a mixed bag. Lee is almost entirely wasted, in a role that could have been played by virtually anyone, and Lewis is forgettable. But I did like Strasberg’s heroine who, despite her initial tendency to bolt (as fast as her wheels can carry her), turns out to be rather plucky and persistent in her investigation. As she tells the doctor at one point, “You say my mind is affecting my legs. You’re wrong. It’s my legs that are affecting my mind.” It’s certainly a little different from the normal disabled character, being someone who is not defined by her predicament – though it is, again, an affliction required by the plot. She’s even capable of joking darkly about it, correcting Robert when he asks, “You were on a horse, weren’t you?”, by replying “The horse was on me.”

All told, it probably waits too long for the moments which have real impact, such as Robert’s dive into the swimming pool, or the revelation of identity through which the ending turns an abrupt 180. By those points, my interest was certainly waning. The film was a moderate success in the United Kingdom, with an intriguingly undersold campaign (above) almost entirely based around Penny’s S-face. But it appears to have done very well on the continent, and its success spurred Hammer and Sangster towards a further slew of paranoid psychological thrillers along similar lines, as the decade progressed. It became one of the rare Hammer films to have a remake proposed, Sony announcing a plan in 2013 to have Juan Antonio Bayona (The Orphanage) direct a new version. However, nothing seems to have come of this. For now, our summerhouses are safe.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.