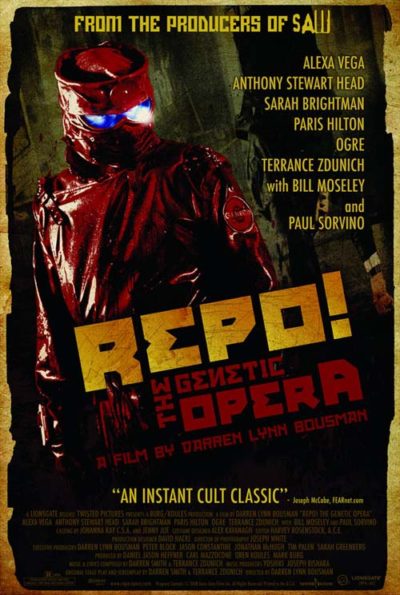

Rating: B-

Dir: Darren Lynn Bousman

Star: Anthony Stewart Head, Alexa Vega, Paul Sorvino, Terrance Zdunich

The year is 2057. The world is dominated by GeneCo, the company under Rotti Largo (Sorvino) that helped defeat a wave of organ failure, by providing transplants – at a cost. And woe betide you, if you feel to keep up with the payments, for they’ll send repo man Nathan Wallace (Head) after you for a friendly chat and the foreclosed organ. However, both Largo nor Wallace have their own issues: the former discovers he is terminally ill and has to decide which of his three dreadful offspring will inherit GeneCo, while his employee has a teenage daughter (Vega) suffering from an incurable blood disease. The two have a connection that goes back a long way; Nathan’s now-dead wife had been engaged to Largo, back before he saved the world. I trust the potential for tragedy, of the Wagnerian kind, needs no emphasis.

I don’t think this is as original as has been claimed in some quarters. While the rock opera [note, not musical: that just contains songs, while this contains almost no spoken dialog] is a genre that’s not exactly been seen much, aspects of this come from – in chronological order of the movie versions – Phantom of the Paradise, The Rocky Horror Show, Hedwig and the Angry Inch and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. The last-named may be the closest, for its mix of arterial spray and show-tunes. Add elements from the likes of Brazil and Blade Runner [while the central notion is close to Python’s Live Organ Donors] and the result is about as original as the average Tarantino film. Still, what emerges is unquestionably its own beast – albeit in much the same way as Frankenstein’s monster.

I don’t think this is as original as has been claimed in some quarters. While the rock opera [note, not musical: that just contains songs, while this contains almost no spoken dialog] is a genre that’s not exactly been seen much, aspects of this come from – in chronological order of the movie versions – Phantom of the Paradise, The Rocky Horror Show, Hedwig and the Angry Inch and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. The last-named may be the closest, for its mix of arterial spray and show-tunes. Add elements from the likes of Brazil and Blade Runner [while the central notion is close to Python’s Live Organ Donors] and the result is about as original as the average Tarantino film. Still, what emerges is unquestionably its own beast – albeit in much the same way as Frankenstein’s monster.

The movie’s strongest suit is its visual style, which is little short of breathtaking: a future world with a dreamlike atmosphere has been created, mostly using sets but with effective use of CGI to add scale. Much credit to cinematographer Joseph White and production designer David Hackl for their sterling work creating a backdrop, into which all the characters fit perfectly. Head is the standout performance, commanding the screen with a combination of pathos, presence and gallows humour; he is no slacker on the singing front either, though having seen him on the London stage as Frank N. Furter, back in the early 90’s, that’s not really a shock. Zdunich appears as a graverobbing drug-dealer, and gets one of the best songs, though his character seems peripheral – it may have served a greater purpose on-stage?

Paul Sorvino is a pleasant surprise [with some research, it seems shouldn’t be]; not so Vega, whose voice comes over as thin and reedy; it’s probably appropriate for her 17-year old character, but lacks anything to make it a pleasure to listen to. Sara Brightman, as an opera singer whose site was restored by GeneCo, also makes an impression, albeit probably as much for her enormous false eyelashes as anything else. Paris Hilton shows up as one of Rotti’s appalling children, and doesn’t suck as much as you might expect, though I’d still have welcomed it if her character’s fate had matched that suffered in House of Wax.

Paul Sorvino is a pleasant surprise [with some research, it seems shouldn’t be]; not so Vega, whose voice comes over as thin and reedy; it’s probably appropriate for her 17-year old character, but lacks anything to make it a pleasure to listen to. Sara Brightman, as an opera singer whose site was restored by GeneCo, also makes an impression, albeit probably as much for her enormous false eyelashes as anything else. Paris Hilton shows up as one of Rotti’s appalling children, and doesn’t suck as much as you might expect, though I’d still have welcomed it if her character’s fate had matched that suffered in House of Wax.

For an opera, it’s a major weakness that the tunes are eminently forgettable: less than 24 hours later, I can’t remember even a couple of notes of any of them. Being charitable, let’s assume they take a few hearings to sink in. Though mostly unremarkable, I liked the neo-industrial feel to most of them [the presence of Ogre from Skinny Puppy, playing another of Largo’s kids, makes a great deal of sense], and there’s enough variety to keep things interesting. Joan Jett shows up at one point, for reasons that escaped me.

Even if the results are wildly uneven, I have nothing but enormous respect for the creators: they clearly went into this with a vision of what they were trying to create, and they refused to compromise it one iota. In a world of increasingly-sterile entertainment, the love that went into this, both in front of and behind the camera, is a pleasure to see. The dedication to and passion for the film shown by Zdunich and Bousman is both obvious and infectious, and is likely a key part of the reason why fans of their work appear to be every bit as enthusiastic.