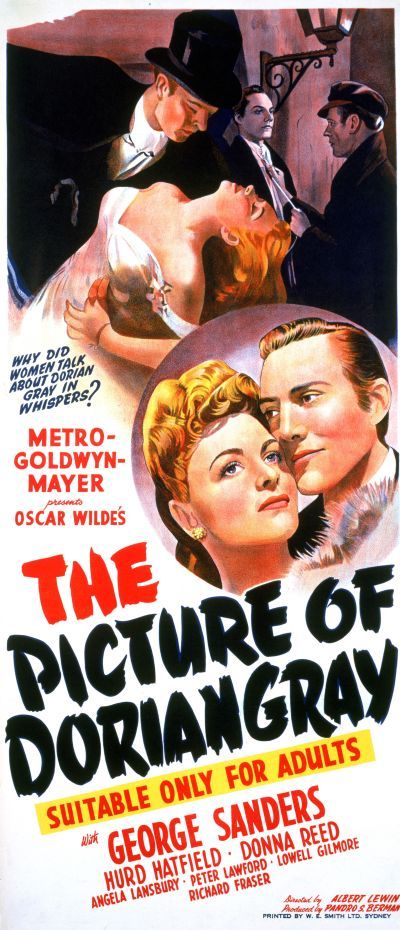

Rating: C+

Dir: Albert Lewin

Star: Hurd Hatfield, George Sanders, Donna Reed, Angela Lansbury

First off, I was prepared to swear blind the title of both this film, and the Oscar Wilde novel on which it is based, was The Portrait of Dorian Gray. Chris felt the same way, but a Google search emphatically confirmed we were wrong. Is this a widespread thing? Or is the apparent Mandela Effect about the title limited purely to Film Blitz Towers? Anyway, the horror genre continues to get a little stronger, year by year, as we head back in time. There were a number of credible candidates for 1945, with decent ratings and a good sample size. This and Dead of Night both received the same IMDb score of 7.5, with Picture coming out on top due to its higher number of votes received.

There were some further down the list that had appeal too. It was difficult to resist titles like Zombies on Broadway, Strangler of the Swamp, or in particular, Pillow of Death. Sadly, the last turned out not to be about a cushion inhabited by the vengeful spirit of a serial killer, and far less interesting: “An unfaithful attorney suspected of murdering his wife.” But there was no credible reason than to go with the one at the top, based on Wilde’s somewhat notorious book, his only novel, published in 1891 (after a shorter version the year before). It was fairly controversial at the time for its homoerotic themes, and passages were read in court during his subsequent trials.

Needless to say, not much trace of that remains in this adaptation. Indeed, it adds a second heterosexual romance, between Dorian and Gladys Hallward (Reed), not present in the book – just so there’s no doubt. It was the first sound movie based on the novel, though there had been a number of silent versions, going back as far as 1910. The plot probably doesn’t need a great deal of description. Dorian Gray (Hatfield), after having his portrait painted, realizes that it will remain forever unchanging, while he will grow old and lose the bloom of youth. So he sells his soul – in this case to a statue of an Egyptian cat deity – to remain eternally young, with the picture reflecting the moral and physical decline as a result of his sinful life.

Needless to say, not much trace of that remains in this adaptation. Indeed, it adds a second heterosexual romance, between Dorian and Gladys Hallward (Reed), not present in the book – just so there’s no doubt. It was the first sound movie based on the novel, though there had been a number of silent versions, going back as far as 1910. The plot probably doesn’t need a great deal of description. Dorian Gray (Hatfield), after having his portrait painted, realizes that it will remain forever unchanging, while he will grow old and lose the bloom of youth. So he sells his soul – in this case to a statue of an Egyptian cat deity – to remain eternally young, with the picture reflecting the moral and physical decline as a result of his sinful life.

Well, allegedly sinful life, anyway. Don’t expect any details here, beyond vague reports that “Curious stories were current about him,” and that he hung around the East End a lot. Responsibility for his actions, to some extent, must belong to his friend, Lord Henry Wotton (Sanders). He has a cynical nature to life, and encourages Gray to enjoy all its pleasures, telling him, “There’s only one way to get rid of a temptation, and that’s to yield to it.” That cynicism applies in particular towards women, in a way that reminded us of Professor Higgins in My Fair Lady. “Women treat us just as humanity treats its gods,” he says. “They worship us and keep bothering us to do something for them.” It’s very easy to hear his lines in Wilde’s voice.

His impact on Gray starts by destroying his relationship with East End songbird, Sibyl Vane (Lansbury), by insisting Dorian test her morality. When she fails, he cuts her off brutally, causing her to commit suicide. It’s this that leads to the first changes in the portrait. When Gray notices, he stashes the picture away and decides to embrace fully the hedonistic lifestyle. Fast forward 18 years: he still looks the same, but the picture does not. The painting probably offers the film’s most memorable moments, because in a highly effective tweak, there are sections where the black-and-white movie bursts into full Technicolor for both the original painting, and the macabre, twisted version into which it turns (below).

Credit Ivan Le Lorraine Albright for the latter, and it’s truly a striking creation, the stuff of nightmares – the painting now hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago. Its sudden appearance, particularly in its full, Technicolour glory, is in sharp contrast to the obtuse understatement which has previously informed the film. You don’t really need to know the specifics: whatever Gray did, was clearly very, very bad. The piece of art makes the point more effectively than all the dark hinting, and insinuations about Dorian slumming it in Whitechapel. It is true to say, it feels as if the film peaks dramatically too early, with Sibyl’s death. Gladys never makes quite the same impression. I certainly understand why Lansbury was nominated for an Oscar (losing the Best Supporting Actress category to Anne Revere in National Velvet), and Reed was not.

I also suspect the way the story skips over close to a generation may weaken things, meaning there’s no sense of gradual decay. Hatfield might be a little too bland for the role as well. The top-billed Sanders would have been more effective. After all, a fear of mortality is hardly the exclusive provenance of the twenty-something. Personally, the more I feel my body beginning to crack, the more my mind wants to cling onto its youth. I certainly wasn’t raging against the dying of the light when I was 22. I’m not going to lie: at 110 minutes, this becomes subject to the law of diminishing returns in the second half, and I might have been looking up the whole Picture/Portrait thing on my phone at times.

I also suspect the way the story skips over close to a generation may weaken things, meaning there’s no sense of gradual decay. Hatfield might be a little too bland for the role as well. The top-billed Sanders would have been more effective. After all, a fear of mortality is hardly the exclusive provenance of the twenty-something. Personally, the more I feel my body beginning to crack, the more my mind wants to cling onto its youth. I certainly wasn’t raging against the dying of the light when I was 22. I’m not going to lie: at 110 minutes, this becomes subject to the law of diminishing returns in the second half, and I might have been looking up the whole Picture/Portrait thing on my phone at times.

It’s a shame, as the early going is highly effective, particularly in showing the way Dorian becomes influenced by Lord Henry – more by accident than deliberate design. The narration, voiced by an uncredited Cedric Hardwicke, often comes straight from the original text, and both fills in emotional gaps, and is entertaining in its own right – not often you can say that about a cinematic voice-over. However, Hatfield was not strong enough to hold my attention, when on screen without Sanders or Lansbury. I feel this would have been better (and, certainly, more fun) had it gone down the Edge of Sanity route. Needs more wallowing in depravity.

This article is part of our October 2025 feature, 31 Days of Vintage Horror.