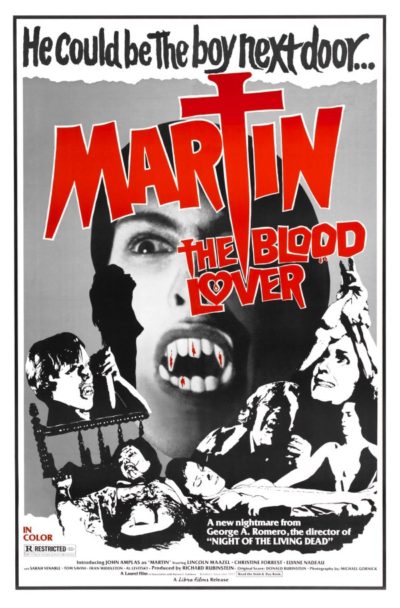

Rating: B

Dir: George A. Romero

Star: John Amplas, Lincoln Maazel, Christine Forrest, Tom Savini

There’s some argument over the year for this. I’ve gone with the IMDb’s opinion of 1976, but the Wikipedia is titled “Martin (1978 film)”. Adding to the confusion, the article there begins by calling it, “a 1977 American psychological horror film.” Not that it matters. I just want to stave off the inevitable emails from Romero fans, since I know how… enthusiastic they can be. I don’t always agree. Romero is like Tobe Hooper to me: someone who lucked into a genre classic early on, and spent the rest of his career trying to live up to it – largely unsuccessfully. Here, though, I can see their point, with a uniquely grubby contemporary vampire film which stands the test of time.

It feels like it’d be a good double-bill with (or counterpoint to) another seventies entry in that genre, Daughters of Darkness. Both are understated in nature, yet could hardly be more different in settings or protagonists. Instead of a five-star hotel in an off-season Belgian seaside resort, we get the urban blight of Pittsburgh. At the time the city was dying as its long-term lifeblood, the steel industry, went elsewhere, sucking the city dry, making it an apt location for a film of this kind. And, instead of an urbane, genteel member of the nobility, we get Martin Matthias (Amplas), a twenty-something young man who might, or might not, be a Romanian vampire in his eighties. This film, quite deliberately, never comes to a conclusion regarding this.

What matters is that Martin believes himself to be one – he identifies as a vampire, if you will. Had there been Twitter in those days, his bio pronouns would probably have been “Count” and “Drac.” Indeed, the former is what Martin is called by a local night-shift DJ, whom he calls to unburden himself, becoming a bit of a local media sensation as a result. Not everybody who indulges Martin’s world-view is as sympathetic. In particular, his cousin Tateh Cuda (Maazel), with whom Martin is staying, fully buys into the superstition, calling Martin a “nosferatu”, and festooning the house with garlic and crosses. Martin is unimpressed, pointedly stating, “Things only seem to be magic. There is no real magic. There’s no real magic ever.”

What matters is that Martin believes himself to be one – he identifies as a vampire, if you will. Had there been Twitter in those days, his bio pronouns would probably have been “Count” and “Drac.” Indeed, the former is what Martin is called by a local night-shift DJ, whom he calls to unburden himself, becoming a bit of a local media sensation as a result. Not everybody who indulges Martin’s world-view is as sympathetic. In particular, his cousin Tateh Cuda (Maazel), with whom Martin is staying, fully buys into the superstition, calling Martin a “nosferatu”, and festooning the house with garlic and crosses. Martin is unimpressed, pointedly stating, “Things only seem to be magic. There is no real magic. There’s no real magic ever.”

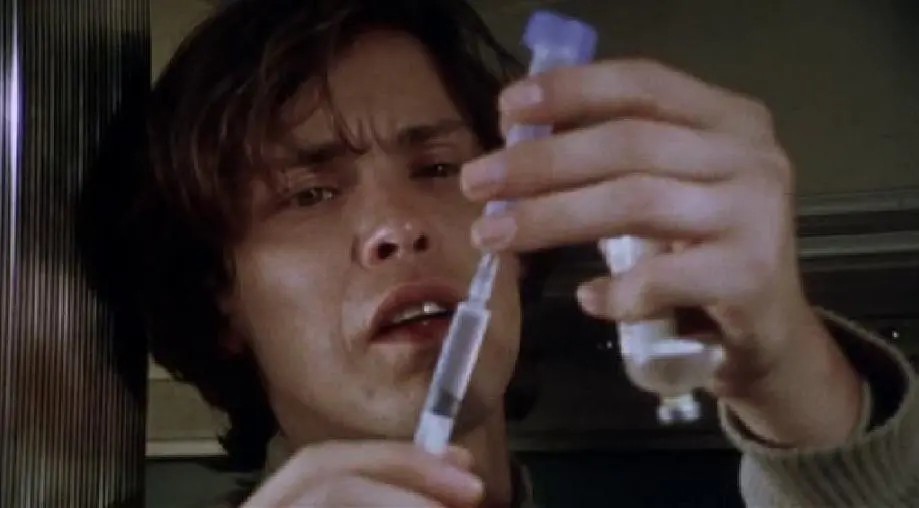

He’s not wrong. Martin possesses no mystical strengths or weaknesses at all. He can’t hypnotize victims with his gaze; he has to inject them with a sedative, then wait for them to fall asleep. No transforming into a bat and flying up to their balcony. Instead, Martin buys a remote control gadget to open their garage doors. This is vampirism as a prosaic undertaking, robbed of all spiritual overtones. Though he has visions – possibly memories, possibly not – which are of a more classical form, all EuroTotty in Gothic nightgowns, holding candelabras and beckoning winsomely. It helps conceal the sordid reality, in which Martin is breaking into a suburban Pittsburgh carport, to feed on a bored housewife. Who is actually having some afternoon delight with her bit on the side.

Hard to say who is more surprised by the resulting encounter. What follows has the air of farce, as Martin runs around the house, trying to subdue not one, but two victims. Again, it’s a far cry from the act of vampirism as seduction. This is ugly, messy and nor pleasant for vampire, victim or viewer. To that end, it appears Martin is actually a virgin, until seduced by another bored housewife, Abbie Santini, whom he meets delivering groceries for his cousin’s shop. [Dammit, when I was a teen, I delivered newspapers and prescriptions in my hometown for four years. Number of seduction attempts by bored housewives: 0] This may be evidence against the vampire theory: any genuine 84-year-old would probably have got lucky at some point during the previous decades.

Somewhat related is Martin’s relationship with Christina (Forrest), Cuda’s orphaned granddaughter. She had no truck with her grandfather’s old-fashioned ways – whether related to vampirism or not, such as his refusal to get a phone in the house. She eventually leaves town with her boyfriend (Savini), even though she freely admits he is simply her escape route. Meanwhile, Martin struggles to come to terms with his emotional imprinting on Abbie, and after Christina leaves, goes on a killing spree. It is in direct violation of Cuda’s firm order not to eat local, and leads to the confrontation with his cousin which ends the film. Very abruptly, it must be said.

At least in this, standard version. Romero wanted to release his cut of the film, running 150 minutes, in black-and-white. The distributors disagreed, and the Romero cut was considered lost. Until last year, when it turned up on three 16mm reels. Those sold at auction in July for $51,200, though copyright remains with the usual parties. Whether it will eventually be made publicly available, remains to be seen. I would be interested, though can’t say I reached the end of the regular edition and thought, “There’s a movie which needs to be 60 minutes longer.” On the other hand, it’s a delicious, palate cleanser to young adult vampire nonsense like the Twilight franchise. Martin does not sparkle, to put it mildly, and is among the most realistic depictions of vampirism in cinema, at least as a psychological condition.

At least in this, standard version. Romero wanted to release his cut of the film, running 150 minutes, in black-and-white. The distributors disagreed, and the Romero cut was considered lost. Until last year, when it turned up on three 16mm reels. Those sold at auction in July for $51,200, though copyright remains with the usual parties. Whether it will eventually be made publicly available, remains to be seen. I would be interested, though can’t say I reached the end of the regular edition and thought, “There’s a movie which needs to be 60 minutes longer.” On the other hand, it’s a delicious, palate cleanser to young adult vampire nonsense like the Twilight franchise. Martin does not sparkle, to put it mildly, and is among the most realistic depictions of vampirism in cinema, at least as a psychological condition.

The performances are all good, and on the basis of what he delivers here, it’s a bit of a shame that Amplas in particular did not have more of a career. His depiction of Martin balances nicely between sympathetic and scary. In a world where it is now demanded we accept without question, whatever people proclaim to be their identity, Martin perhaps shows the potential dangers which can result from such an all-embracing and tolerant approach. Sometimes mental illness is simply a sickness, and needs to be called out as such, rather than being indulged. Just because you think you’re Napoleon, does not mean society owes you a three-cornered hat…

This article is part of our October 2022 feature, 31 Days of Classic Horror.