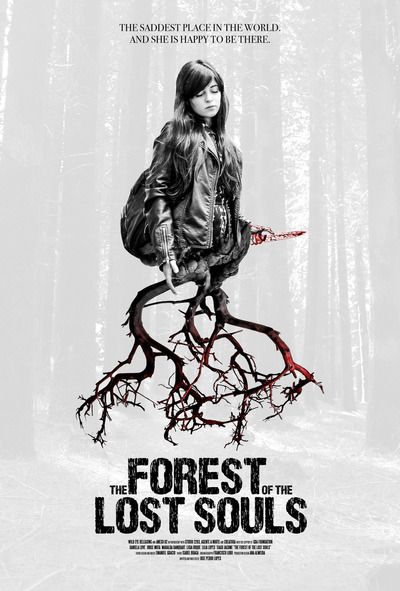

Rating: C+

Dir: José Pedro Lopes

Star: Daniela Love, Jorge Mota, Mafalda Banquart, Lígia Roque

a.k.a. A Floresta das Almas Perdidas

I’ve never been to Portugal. Even in my college days, when I Inter-railed my way around almost every country in Europe, this side of the Iron Curtain, Portugal was one of the few reasonably sized ones I missed. That and Finland. Both for much the same reason, being stuck on the edge, and kinda difficult to reach. You can’t pass through Portugal on your way somewhere else. You pretty much have to go there, and at the time it felt like the “Is Pepsi alright?” version of Spain. I’d been to Spain and didn’t feel the need to go all the way through it, simply to visit a smaller version with crinkly edges.

Forty years later, I am older, wiser… and still Googling, “differences between Spain and Portugal”. Being Scottish, I wonder if the relationship between the two countries is like that between Scotland and its only land pal, England, which is also larger and had a bit more geopolitical clout. Do the Portuguese have the same kind of reflex, adversarial reaction to their neighbour? Spain and Portugal did spend twenty-seven years at war with each other in the seventeenth century. The difference to Scotland being, Portugal ended up winning its independence back. How might history be different had Bonnie Prince Charlie not stopped at Derby in 1745, and subsequently been beaten at the Battle of Culloden. Probably fewer depressing folk ballads, I imagine, and less of an inferiority complex.

Anyway. Back in Portugal, it has a long history of cinema, dating back to 1896’s Saída do Pessoal Operário da Fábrica Confiança. Horror, though? Nowhere near as much, and that’s a little surprising when you compare the country’s output to that of its former colony, Brazil. Of course, the latter has the advantage of scale, possessing twenty times the population of Portugal. But it feels that its cinema went in a different direction from the motherland. The most famous Portuhorror is likely 1971 Spanish-Portuguese co-production, Tombs of the Blind Dead. Though we had to wait until 2006 for Blood Curse (Coisa Ruim), often regarded as the first purely Portuguese entry in the genre. It’s the story of Xavier, who moves to a small village, only to discover it has a dark secret, and isn’t very good.

Anyway. Back in Portugal, it has a long history of cinema, dating back to 1896’s Saída do Pessoal Operário da Fábrica Confiança. Horror, though? Nowhere near as much, and that’s a little surprising when you compare the country’s output to that of its former colony, Brazil. Of course, the latter has the advantage of scale, possessing twenty times the population of Portugal. But it feels that its cinema went in a different direction from the motherland. The most famous Portuhorror is likely 1971 Spanish-Portuguese co-production, Tombs of the Blind Dead. Though we had to wait until 2006 for Blood Curse (Coisa Ruim), often regarded as the first purely Portuguese entry in the genre. It’s the story of Xavier, who moves to a small village, only to discover it has a dark secret, and isn’t very good.

Horror films since then have been sporadic, though Amelia’s Children made something of a splash outside of Portugal earlier this year. There is a big horror festival, Motel/X, which has taken place in Lisbon for a week every September since 2007, and there’s Fantasporto as well. Scanning their programs, local features are heavily outnumbered by screenings of overseas films, and it took several stabs before I found something appropriate for this feature. The first, Adrift, was so terrible I apparently refused even to write a review of it. I think it was more of a thriller? Then there was Inner Ghosts, which came closer, but was entirely in English with a British lead actress, and felt a bit of a cop-out. Reading reviews of Amelia’s Children, it seemed almost parody. So here we are instead.

There are things to admire, yet also obvious flaws. It begins in the (fictional) Portuguese version of Japan’s notorious Aokigahara Forest, a place where people go to kill themselves. Two prospective suicides meet. One is Ricardo (Mota), a middle-aged man who feels he has failed his wife and daughter. The other is Carolina (Love), a young Goth woman who may or may not be serious about taking her own life. She might just enjoy hanging out in the creepy place, and talking to (more or less) like-minded individuals. Carolina provides Ricardo with helpful tips, since he is singularly ill-prepared. He has not written a suicide note, and has no backup plan, in case he can’t steel himself to use the knife he brought.

However, we eventually discover that Carolina may not be quite the live-action suicide helpline she appears. Leaving the forest, she starts to take a suspicious interest in Ricardo’s family: his daughter Filipa (Banquart) and wife Joana (Roque). They have no idea where he has gone or what his intentions were. This is where the film struggles hardest, mostly because Filipa (below) is a vapid teenage Barbie, whose apparent lack of personality stands in sharp contrast to Carolina’s hidden, to the point of labyrinthine, depths. Despite the film running a crisp 71 minutes, the section depicting Filipa’s home life may have you making “hurry up” gestures in the direction of the screen. Then Carolina shows up, and things get pretty damn dark. Which is saying something, considering we started out in a suicide forest.

It’s all a little too loosely structured to be utterly compelling, with some elements which feel undercooked, or never go anywhere much. The significance of Ricardo’s other, dead daughter is unclear, and Filipa’s boyfriend might as well not have been present. Despite the brief duration, it feels padded and we’d have been better off with more background on Carolina. How did she get to where she is? What makes her tick? It feels as if Lopes is deliberately being enigmatic about his lead, and it’s a waste, because she is the best thing in this. Carolina is the one person here who’d be fun to hang out with. Just put away all pointed objects first.

It’s all a little too loosely structured to be utterly compelling, with some elements which feel undercooked, or never go anywhere much. The significance of Ricardo’s other, dead daughter is unclear, and Filipa’s boyfriend might as well not have been present. Despite the brief duration, it feels padded and we’d have been better off with more background on Carolina. How did she get to where she is? What makes her tick? It feels as if Lopes is deliberately being enigmatic about his lead, and it’s a waste, because she is the best thing in this. Carolina is the one person here who’d be fun to hang out with. Just put away all pointed objects first.

The film is shot in crisp monochrome, which certainly enhances the atmosphere. The same goes for Emanuel Grácio’s effective score. I was just left with a sense of unfulfilled potential. This could have been a deep dive into genuinely unexplored territory: instead, it only skims the surface. While this is done in an interesting manner, I doubt many viewers will leave fully satisfied. There aren’t many times I feel a film being too short is a flaw. Twenty well-executed, additional minutes here could have paid significant dividends, elevating this beyond the achieved level of a cinematic amuse-bouche.

This review is part of our October 2024 feature, 31 More Countries of Horror.