Rating: C-

Dir: David Lynch

Star: Jack Nance, Charlotte Stewart, Judith Anna Roberts, Laurel Near

What is the meaning of life? What happens after we die? And why the hell am I watching Eraserhead? These are the great existential questions of our time. For when I came up with the list of movies picked by our objective criteria, this is the only one where I thought about playing my executive privilege card, and going with Suspiria instead. Chris stoically sat through the other 30 – even Multiple Maniacs – but when I mentioned Eraserhead, I was presented with The Face. Every married man knows The Face: the “do not test me” one. This was therefore watched solo, in our bedroom, with the door closed, a fate normally reserved for Philippino women-in-prison movies.

There was discussion of getting some acid, and seeing if it helped. Sadly, the deadline arrived before the LSD did, and I was on nothing more than coffee for the viewing. Hey, Lynch would no doubt approve. Thirty-odd years had likely passed since my last engagement with the full feature, yet it still resonated as an incredibly tedious ordeal. My recollection was it being the very definition of art-house nonsense: pretentious and pompously “deep”, without being capable of getting any coherent point over. This seemed confirmed by the opening sentence of the Wikipedia synopsis: “The Man in the Planet is moving levers in his home in space, while the head of Henry Spencer floats in the sky. A spermatozoon-like creature emerges from Spencer’s mouth, floating into the void.” Okay: that’s why I hated it, and had considerable trepidation as I hit ‘play’.

However, I didn’t loathe it quite as much now. Oh, I am still some way short of liking the movie, and if I don’t see it for another 30 years, I’ll be perfectly fine with that. Yet perhaps I have a better handle on it being a nightmare about parenthood, having experienced its joys myself. Admittedly, I arrived slightly further into the process, but I’d argue dealing with those pesky teenage years is at least as troublesome as caring for a premature mutant with a skin condition that never stops crying. Yet beyond that, much of it remains too obscurist to work. Lynch said, “No one, to my knowledge, has ever seen the film the way I see it. The interpretation of what it’s all about has never been my interpretation.” That seems like a “you” problem, David. For what we’ve got here, is failure to communicate.

However, I didn’t loathe it quite as much now. Oh, I am still some way short of liking the movie, and if I don’t see it for another 30 years, I’ll be perfectly fine with that. Yet perhaps I have a better handle on it being a nightmare about parenthood, having experienced its joys myself. Admittedly, I arrived slightly further into the process, but I’d argue dealing with those pesky teenage years is at least as troublesome as caring for a premature mutant with a skin condition that never stops crying. Yet beyond that, much of it remains too obscurist to work. Lynch said, “No one, to my knowledge, has ever seen the film the way I see it. The interpretation of what it’s all about has never been my interpretation.” That seems like a “you” problem, David. For what we’ve got here, is failure to communicate.

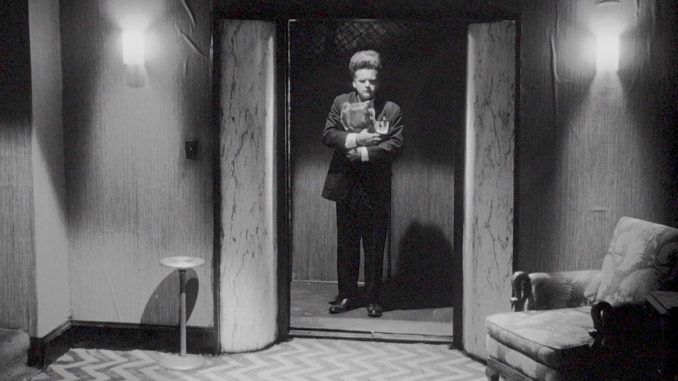

The first half is relatively mundane, as least compared to what’s to come. Henry Spencer (Nance) lives in a post-industrial hellhole of a city, and is on vacation from his job at a printers. His girlfriend, Mary X (Stewart) invites him to meet her parents, in a credible candidate for Most Awkward Dinner Party Ever. It ends with her mother revealing to Henry that Mary had become pregnant, and given birth to…something, though as Mary says, “They’re still not sure it is a baby!” Mom orders the couple to get married and begin caring for the infant, until the incessant sounds it makes help drive Mary to the brink, and she flees, leaving Henry alone to care for it. His sanity begins to crack too, and infanticide begins to seem an appealing proposition. Yeah: worst vacation ever.

The words “His sanity begins to crack” covers a wide range of what-the-fuckness, which I will say has rarely been matched over the 45 years since its release. It’s easy to understand why it became one of the first midnight movies, because some kind of reality altering substance is almost essential here. “Imagine the cinematic equivalent of the third sleepless night after being struck down with the world’s nastiest head cold,” wrote one reviewer, in an attempt to put over the trippy nature of this viewing experience. He’s not wrong: I’d say it was more a criticism than an endorsement though. Sleepless nights and head colds are not something I do for fun, and nor is Eraserhead. I am not David Lynch’s therapist, either.

There are no shortage of bizarre and surreal visuals, most obviously the multiple weird dream sequences. These involve The Lady in the Radiator (Near) stomping on spermatazoa-shaped creatures, like some bizarre crush video, and later warbling, “In heaven, everything is fine. You’ve got your good things, and I’ve got mine,” in an apparent endorsement of child murder. Then Spencer’s head falls off, landing on the street below, and is brought to a factory where it is transformed into pencil erasers. You should repeat that sentence out loud, slowly and savouring each word. My problem with this kind of thing, is that I feel surrealism works better in paintings than in movies: the former don’t need to have a “point”, something which Eraserhead‘s second half conspicuously lacks.

There are no shortage of bizarre and surreal visuals, most obviously the multiple weird dream sequences. These involve The Lady in the Radiator (Near) stomping on spermatazoa-shaped creatures, like some bizarre crush video, and later warbling, “In heaven, everything is fine. You’ve got your good things, and I’ve got mine,” in an apparent endorsement of child murder. Then Spencer’s head falls off, landing on the street below, and is brought to a factory where it is transformed into pencil erasers. You should repeat that sentence out loud, slowly and savouring each word. My problem with this kind of thing, is that I feel surrealism works better in paintings than in movies: the former don’t need to have a “point”, something which Eraserhead‘s second half conspicuously lacks.

I’m glad this film exists, and eventually found its audience despite a premiere in front of an audience of twenty-five, and initial reviews largely along the lines of Variety‘s, “A sickening bad-taste exercise… little substance or subtlety.” If it hadn’t, we likely would not have enjoyed the likes of Blue Velvet, where Lynch’s gift for visual style was paired with a more formal structure, to the benefit of both. Everyone has to start somewhere. Beginning your career by rejecting almost every conventional rule of cinematic storyelling, seems oddly close to arrogance on the film-maker’s part. These rules, by and large, arose for good reason, allowing you to connect with the audience and provoke the intended emotion in them.

Yet as mentioned above, nobody has “got” this movie, according to its own director. The “everyone can interpret it their own way” school of art always seemed like a lazy one to me, the equivalent of throwing a party and expecting the guests to provide all the booze and snacks. I’m especially dubious when the artist hasn’t first proven their credentials, and with Lynch’s film-making experience at this point limited to a handful of shorts, I will continue to regard this one as annoyingly over-rated

This article is part of our October 2022 feature, 31 Days of Classic Horror.