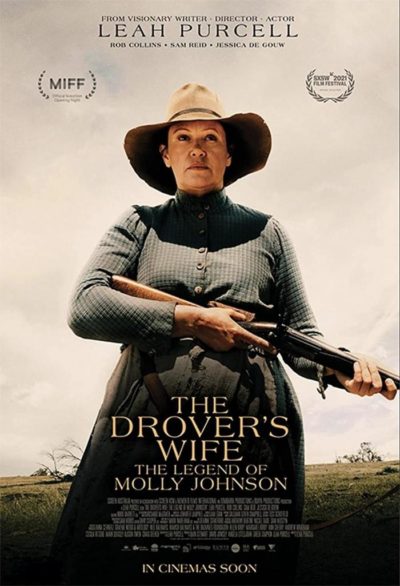

Rating: C-

Dir: Leah Purcell

Star: Leah Purcell, Rob Collins, Sam Reid, Jessica De Gouw

The Drover’s Wife was originally a short story written by Australian author Henry Lawson in 1892. But it seems to be a bit of an obsession for Purcell. She turned it into a play in 2014, a novel in 2019, and now this movie, which she wrote, directed and starred in. Though based on this, she is definitely not interested in a straightforward adaptation. The original story was a trifle at only 3,200 words, and a fairly straightforward “woman against nature” tale. Purcell has used it as a foundation on which to bolt issues of racism and sexism – the 19th century outback not exactly being a time and place where woman and the Aboriginal natives were treated as equals.

In particular, it’s the story of Molly Johnson (Purcell), a mother of three, with a fourth about to arrive, any day. She’s left to care for the family with her husband absent, gone off on a sheep-herding job that will take months to complete. She crosses path with the new town constable, Sergeant Klintoff (Reid), and his wife, Laura (De Gouw), recently arrived from England. But more dramatically, an escaped Aboriginal prisoner, Yadaka (Collins) shows up, and helps Molly with the birth. She gives him food and shelter in exchange, but this leads to a series of awkward truths being revealed, their topics including both Molly’s own history, and the real reason for her husband’s absence. Neither of which fit well with the local settlers and their opinions on race and gender.

It all feels rather worthy, in that it’s clear Purcell has an agenda, and this occasionally gets in the way of the story she wants to tell. The story relies too much on coincidence, e.g. what are the odds of Laura being a vigorous campaigner for the rights of battered women? It also feels as if Molly is the only person in the entire community who is not aware of her ancestry. These occasionally clunky moments do leave the narrative teetering on the edge of derailment, and it’s better when it avoids the obvious lecturing. Molly stating up front, on encountering Yadaka, “Cross me and I’ll kill you. I’ll shoot you where you stand, and I’ll bury you where you fall,” tells us much more about her character than all of Purcell’s transplanted 21st-century idealism.

It all feels rather worthy, in that it’s clear Purcell has an agenda, and this occasionally gets in the way of the story she wants to tell. The story relies too much on coincidence, e.g. what are the odds of Laura being a vigorous campaigner for the rights of battered women? It also feels as if Molly is the only person in the entire community who is not aware of her ancestry. These occasionally clunky moments do leave the narrative teetering on the edge of derailment, and it’s better when it avoids the obvious lecturing. Molly stating up front, on encountering Yadaka, “Cross me and I’ll kill you. I’ll shoot you where you stand, and I’ll bury you where you fall,” tells us much more about her character than all of Purcell’s transplanted 21st-century idealism.

It is a little odd though, since this suggests a character who takes no shit from anyone. Yet for the narrative to unfold as it does, Molly has to be a perpetual victim, and these two aspects seem increasingly to contradict each other, the deeper into the movie we go. You will likely be able to tell where this going with a good thirty minutes left, and you’re then left waiting for events to play out. I suspect Purcell was left wanting us to feel righteous indignation at a miscarriage of justice, along the lines of Dancer in the Dark. I felt more like I had been delivered a committed lecture than told a story.