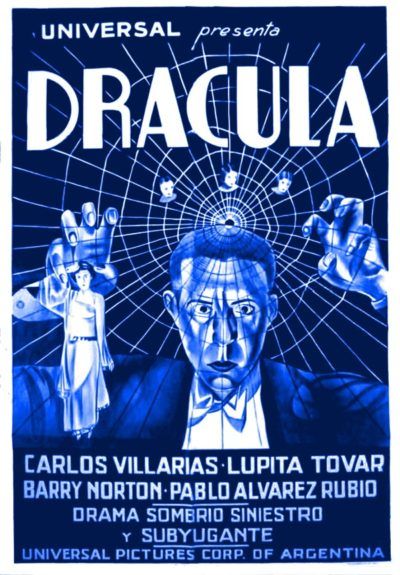

Rating: C+

Dir: George Melford

Star: Carlos Villarías, Lupita Tovar, Barry Norton, Pablo Álvarez Rubio

You may be thinking, “Hang on. Dracula? 1931? Isn’t that the Tod Browning one, with Bela Lugosi?” Yes… and no. Notice the first A in the title has a little slash above it. For this is the Spanish language version, based on the same script, made at the same time and on the same set. OK, not quite the same time: that would have been a bit confusing. But after Browning finished for the day, Melford and his cast and crew would show up to take over, and make their movie at night. Melford actually watched the footage Browning had already shot, and look for ways to improve on it. There’s a good case to be made that he succeeded, despite completing his version in half the time of Browning.

Before we get to that though, we should look at why this was done. Silent films were, for obvious reasons, easy to alter for an international audience. Just edit the intertitles and you’re done. But the arrival of sound in 1927 created a whole new can of worms. Dubbing was an as-yet unknown art, and nobody wanted to go to the cinema and read, so subtitles were out. Studios would instead create as many as six multiple-language versions (MLVs), effectively simultaneous remakes of their own film, with a foreign language cast. Hollywood largely gave up on this approach by the mid-thirties. However, the concept persisted longer in Europe, and it still happens occasionally. For instance, Angelina Jolie’s directorial debut, In the Land of Blood and Honey, was shot in both English and Serbo-Croat versions.

Most of these early MLV prints are now lost, being recycled when the release ended for the silver in them, studios believing the film had no further value. That was considered to have been the fate of the Spanish version of Dracula, though it was still being screened twenty years after coming out. This theatrical longevity may have helped it survive, when so many other MLVs did not. A nitrate original negative was found in a New Jersey warehouse during the seventies, but the third of the movie’s eleven reels was unusable. A complete version couldn’t be restored for a further two decades, until a full copy was found in Havana’s Cinemateca de Cuba.

Most of these early MLV prints are now lost, being recycled when the release ended for the silver in them, studios believing the film had no further value. That was considered to have been the fate of the Spanish version of Dracula, though it was still being screened twenty years after coming out. This theatrical longevity may have helped it survive, when so many other MLVs did not. A nitrate original negative was found in a New Jersey warehouse during the seventies, but the third of the movie’s eleven reels was unusable. A complete version couldn’t be restored for a further two decades, until a full copy was found in Havana’s Cinemateca de Cuba.

Which brings us to the two films. While my review of the original was posted ten months ago, we actually watched them on consecutive evenings. [These October features are a long-term project, research and viewing for each starting more or less on the conclusion of the previous one] This made for a slightly weird experience. There was an obvious sense of déjà vu (or ya visto?), the films sharing footage when appropriate e.g. long shots of Renfield’s carriage going through the Carpathian mountains. Yet, the differences were palpable. This felt less a remake than a remix, stressing different elements – and an extended remix at that, 29 minutes longer than the Browning cut. It’s a surprise, given both movies were working off the same shooting script.

There’s no particular changes to the basic story. What this has, accounting for the greater running-time, is a lot of individual scenes that play out in longer versions. I think this works to its advantage, at least in terms of giving it more chance to establish mood or atmosphere. There are times when the English version feels rushed in comparison, particularly at the end. To be fair, this isn’t necessarily Browning’s fault. His original epilogue was cut, and lost forever, when the film was re-released in 1936 after the Hays Code came into effect. This had Edward Van Sloan, who played Van Helsing, speaking directly to the audience, telling them, “There are such things as vampires,” an unacceptable endorsement of supernatural beliefs in the new era of stricter censorship.

The Spanish Dracula was not troubled by such restrictions, and this is notable in the greater emphasis it places on both religion and sex. The latter is particularly notable in the character of Eva Seward (Tovar), a renamed version of Mina. By contemporary standards, she’s pretty much a slut for Dracula, demonstrating a passion and sensuality that’s surprisingly intense for its time. The costumes she and Lucia Harker wear are more revealing too. Tovar had been appearing in Hollywood silent movies as part of her 7-year contract with Fox, but the talkies proved problematic, until boyfriend Paul Kohner convinced Universal to start making MLVs. Her career was re-galvanized; Tovar continued to act for twenty more years, and lived to the ripe age of 106.

If she is perhaps the movie’s strongest suit, its weakest is Villarías’s portrayal of Dracula, which might cause you to re-evaluate how good Bela Lugosi’s was. Even if the lines are the same (“Yo nunca bebo… vino…”), his delivery is mostly flat and uninteresting, accompanied by the pulling of faces which, frankly, make Villarías look retarded. On the other hand, Rubio does well as Renfield. The character becomes unpredictable, going from apparently sane to near-hysteria in the blink of an eye; likely a more realistic portrayal of insanity, even if less fun to watch than the manic scenery chewing of Dwight Frye. I do have to question the security policies at Dr. Seward’s asylum. These are either particularly ineffectual, or Renfield is a long-lost cousin to Harry Houdini.

If she is perhaps the movie’s strongest suit, its weakest is Villarías’s portrayal of Dracula, which might cause you to re-evaluate how good Bela Lugosi’s was. Even if the lines are the same (“Yo nunca bebo… vino…”), his delivery is mostly flat and uninteresting, accompanied by the pulling of faces which, frankly, make Villarías look retarded. On the other hand, Rubio does well as Renfield. The character becomes unpredictable, going from apparently sane to near-hysteria in the blink of an eye; likely a more realistic portrayal of insanity, even if less fun to watch than the manic scenery chewing of Dwight Frye. I do have to question the security policies at Dr. Seward’s asylum. These are either particularly ineffectual, or Renfield is a long-lost cousin to Harry Houdini.

Overall, I would just give the edge to this version, though it really comes down to a matter of personal taste. The absence of Lugosi is something which can never be overcome: there’s good reason Bauhaus never wrote a song called Carlos Villarías’s Dead. Yet I found enough of the other elements to be better, with a more dynamic approach adopted by Melford, that is probably of greater appeal to a modern viewer. You definitely do not get the sense this is any less of a movie than Browning’s, despite the limited resources and shooting schedule Melford was given.

This review is part of our October 2023 feature, 31 Days of Vampires.