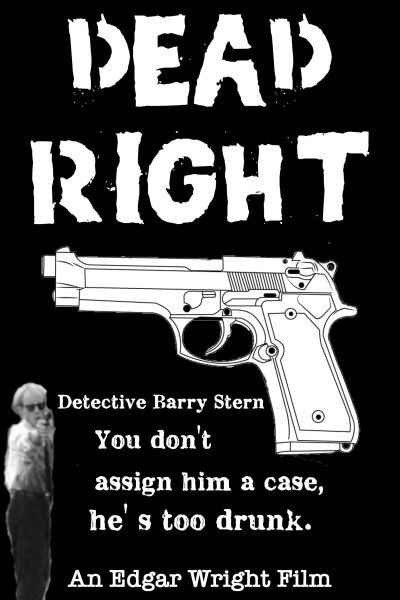

Rating: C+

Dir: Edgar Wright

Star: Edward Scotland, Martin Curtis, Richard Green, Amy Bowles

This 40-minute short is undeniably a precursor to Hot Fuzz, in its lovingly satirical approach to the action genre. However, it likely goes even further, with a frequent breaking of the fourth wall. For example, at one point, the director (Wright in a cameo, above) is taken hostage by the villain, then ends up getting shot and replaced as director by a bit-part actress. So, yeah: it’s like that. Your tolerance will likely closely correlate to that for this kind of meta shenanigans – as well as films that were made on a princely budget of two hundred and seventy-five pounds. Though I’m not sure if the version presented on the Hot Fuzz Blu-Ray might have been fixed at additional cost. The music seems awfully “clean” given the budget, though Wright said, “I actually used some library music and got a friend of mine to do some rock songs for it.”

The plot similarly has a hard-edged cop investigating a series of murders in Wells, and forced to partner up with someone of an opposite personality. The unstoppable (police) force in this case is Barry Stern (Scotland), a.k.a. Dirty Barry. The screenplay for Dirty Harry was originally called Dead Right, and that gives you an idea of where this is going, to the point where the hero recites, word-for-word, Clint Eastwood’s famous speech. The town is plagued by a series of brutal killings, which turn out to be the work of cereal-obsessed supermarket employee Philip Quinn (Curtis); Wright had a Saturday job at the supermarket in question, likely factoring in to its availability as a location for his movie.

It begins with a pre-film sequence spoofing the VHS tapes of the time, which has a similar spot explaining the rating. Here, however, “viewers are warned of poor jokes, bad production values and, frequently, painful acting.” This is not an empty threat. It is, very obviously, written by an 18-year-old who has seen too many films, then made for little more than pocket-money with his mates. However, what really works is the editing. Wright had honed his skills, of all things by splicing footage from a ninth-generation uncut copy of The Evil Dead back into a BBFC-approved tape. The kinetic style, such as the fondness for whip pans, is easily recognizable from his later films. It’s much quicker and flashier than most amateur video productions from the nineties, of which I’ve seen my share.

It begins with a pre-film sequence spoofing the VHS tapes of the time, which has a similar spot explaining the rating. Here, however, “viewers are warned of poor jokes, bad production values and, frequently, painful acting.” This is not an empty threat. It is, very obviously, written by an 18-year-old who has seen too many films, then made for little more than pocket-money with his mates. However, what really works is the editing. Wright had honed his skills, of all things by splicing footage from a ninth-generation uncut copy of The Evil Dead back into a BBFC-approved tape. The kinetic style, such as the fondness for whip pans, is easily recognizable from his later films. It’s much quicker and flashier than most amateur video productions from the nineties, of which I’ve seen my share.

Wright is clearly trying to go for an Airplane!-style approach, shovelling gags at the screen as fast as possible, regardless of narrative coherence, and hoping enough of them land. I’ll admit some do, such as the victim who is utterly oblivious to the intruder in her home. The hit-rate is certainly below that of your typical Zucker production, and the other limitations are often painfully obvious. However, the pace is relentless, and the editing helps keep the energy level high throughout, going a long way to covering those rough patches. It feels less than forty minutes before the end-credits roll, and considering the amateur nature of those involved, that’s no small achievement.