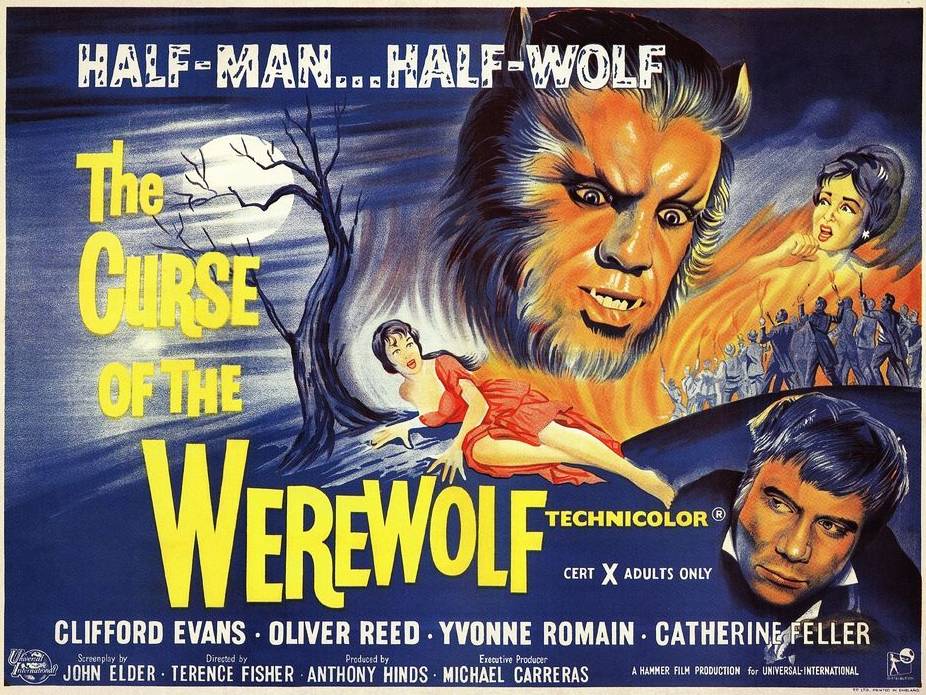

Rating: B-

Dir: Terence Fisher

Star: Clifford Evans, Oliver Reed, Catherine Feller, Warren Mitchell

Probably inevitable that Hammer would eventually go down the road of lycanthropy, though it doesn’t appear this was a commercial success. I imagine they were hoping to launch another horror franchise, but instead, it was one and done: Hammer would never make another werewolf film. Perhaps the cost of licensing put them off, for rather than going the public domain route, as with Dracula and Frankenstein, the studio actually paid for the rights to Guy Endore’s 1933 novel, The Werewolf of Paris. Producer Anthony Hinds wrote the adaptation under his John Elder pseudonym, though there were some hefty changes from the source material.

The most obvious of these is a wholesale shift in time and place, from 1870’s Paris, to the Spain of about a century earlier. This was a business decision by Hammer. They had been working on sets for The Rape of Sabena, a film set during the Spanish Inquisition which was intended to become a double-feature partner for Curse. However, the plug was yanked on that production: reports blame various entities for this, including the British censors, their American distribution partners Columbia, or even the Catholic League of Decency. Regardless, the sets were there, and rather than just tear them down, it was decided by Hammer to relocate their hirsute hero to the southern side of the Pyrenees and make use of the work already carried out.

Much of the political content from the novel also went; the book was set in the Paris Commune, the radical socialist government which briefly ruled France’s capital. However, it has to be said, the portrayal of the ruling classes in Hinds’s adaptation is almost universally harsh, as we’ll see. What also survives from the novel to the movie, is that both protagonist are the product of rape, and as they grow up, experience increasingly violent dreams, which are actually memories of experiences and crimes committed while in their lupine form. Love – whether in the form of a family or a good woman – can repress the blood-lust. However, neither book nor film have this leading to a happy ending; the former has the hero commit suicide, while the movie has an equally tragic conclusion.

Much of the political content from the novel also went; the book was set in the Paris Commune, the radical socialist government which briefly ruled France’s capital. However, it has to be said, the portrayal of the ruling classes in Hinds’s adaptation is almost universally harsh, as we’ll see. What also survives from the novel to the movie, is that both protagonist are the product of rape, and as they grow up, experience increasingly violent dreams, which are actually memories of experiences and crimes committed while in their lupine form. Love – whether in the form of a family or a good woman – can repress the blood-lust. However, neither book nor film have this leading to a happy ending; the former has the hero commit suicide, while the movie has an equally tragic conclusion.

But that’s getting ahead of ourselves, by quite a long way. Before Olly Reed even shows up, which doesn’t happen until around 48 minutes in, the film features not one but two extended prologues. The first of these depicts the conceptual sexual assault. A beggar shows up at the court of Marques Siniestro on the latter’s wedding day, and an off-colour remark gets him tossed into a dungeon. You may recognize the footman who lets the beggar in. He’s played by Desmond Llewellyn, shortly to achieve fame as Q in the Bond movies. Amusingly, Anthony Dawson, who portrays the Marques, would appear alongside Llewellyn as Blofeld, in From Russia With Love and Thunderball. So here, you basically have Q being Blofeld’s flunky…

A bit of HispanoTotty who subsequently refuses the Marquis’s advances, gets thrown in beside the beggar, and unpleasantness ensues. She escapes and is found by the kindly Don Alfredo Corledo (Evans), but dies in childbirth on Christmas Day – the last makes for a “cursed” child, according to the Don’s helpful housekeeper, Señora Wikipedia. I may have made that name up, though judging by the way the water in the baptismal font boils, she’s not wrong. This takes us to the half-hour mark, and into the second prologue. Something (or someone) is tearing out throats of the local livestock, and it turns out to be the young Leon Corledo (Justin Walters, who does look impressively like a pre-pubescent version of Reed). For an incident on a hunting trip has awakened his inner animal, and given the boy a taste for blood.

Local inn-keeper come huntsman Pepe Valiente (Mitchell. who’d later play Alf Garnett – for American readers, that’s the original, British version of Archie Bunker) is convinced he shot the “wolf”. Eventually, not least due to little Leon’s hairy palms, Don Alfredo puts two and two together. However, the local priest tells him, “Whatever weakens the spirit of the beast – warmth, fellowship, love – raise the human soul,” and give it a chance to exorcise the unwanted elements. And, for a decade or so, a good family environment keeps the wolf from Leon’s door. Though Pepe never forgets, wearing a silver bullet crafted from his wife’s crucifix around his neck.

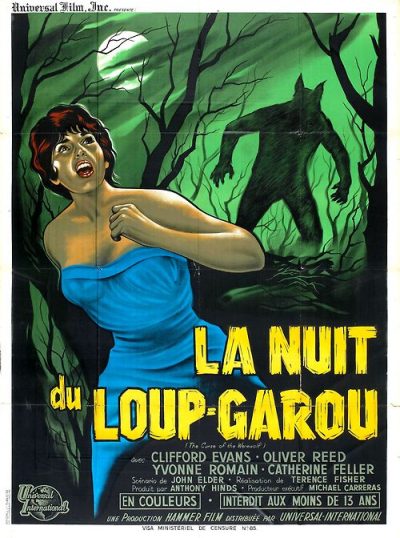

Finally, well into the second half, we reach the main plot. Leon (Reed) has grown up, and is moving out to work in the wine cellar of Don Fernando Gomez. There is quickly a mutual attraction with Don Fernando’s daughter, Christina (Feller), though she is betrothed to another unflattering portrayal of the upper classes, chinless wonder Rico Gomez. After apparently losing her, Leon goes to drown his sorrows with a workmate art a local brothel on the night of the full moon. Again, quoting the priest: “Whatever weakens the human soul – vice, greed, hatred, solitude – these bring the spirit of the wolf to the fore.” Leon, in wolf form, kills his colleague and a prostitute (though the scene depicted in the publicity still, top, never comes to pass), and despite intervention by both Don Alfredo and Christina, is jailed for the murders.

Mere iron bars are not enough to keep him inside, and he breaks out, rampaging up and down the town’s buildings like a parkour lycanthrope, pursued by the traditional mob with torches. With no way out, Don Alfredo uses Pepe’s bullet to slay Leon. It’s a sad ending, the film’s sympathies having been entirely with the werewolf, who is depicted as a victim of circumstance, his fate likely sealed at conception. Reed is excellent in the role, but the structure is a real problem, with things simply taking too long to reach the meat of the situation. What takes more than 45 minutes to tell, could have been done in ten, with the movie expanding instead on Leon’s adult struggles.

In some ways, you can see why Hammer decided not to revisit this particular monster: it’s not one which renders itself to much variation. If you look at cinema history, werewolf films tend largely to be much of a muchness, in contrast to a much broader swathe of vampire movies, covering everything from Nosferatu to The Lost Boys. The transformation scene poses another problem, one to which special effects would not be able to do justice, until the early eighties, after Hammer had ceased to be. But given these constraints, this is by no means bad, and does tragic justice to its protagonist in a way most other entries in the werewolf genre can’t match.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.