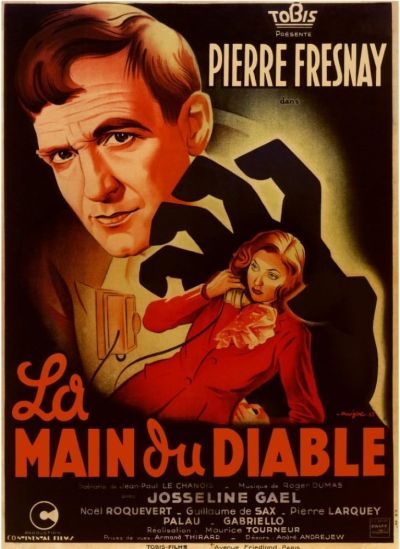

Rating: B

Dir: Maurice Tourneur

Star: Pierre Fresnay, Josseline Gaël, Palau, Noël Roquevert

a.k.a. La main du diable

Plenty of options here, with nineteen films classified as horror and reaching the thousand vote cut-off from the year. However, an executive decision was made to exclude the highest-rated among them. That was French film, Le Corbeau, partly because it seemed a little too fringey, particularly when there were other options. The synopsis there was, “A French village doctor becomes the target of poison-pen letters sent to village leaders, accusing him of affairs and practicing abortion.” It did sound interesting though, so I may opt to review it elsewhere. In addition, it was directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot; he already had an entry in the series, having made Les Diaboliques. Let’s share the love a bit instead.

The second-ranked film was also from France, and I was tempted to do a double-bill of this and the next-highest entry, because they were directed by a father and son duo. For third place went to I Walked With a Zombie, made by Maurice’s son Jacques. However, he’ll be getting his own moment in the sun very shortly, so we’ll stick with just the father. Maurice had enjoyed a successful career in silent-era America, and indeed, had become a US citizen in 1922. His Hollywood period came to a sharp end after his removal from Jules Verne adaptation The Mysterious Island in 1928 – the second of three directors to work on the big-budget production – a movie which eventually proved a costly flop for MGM. Tourneur returned to France, continuing his film-making career there.

This is, on one level, your typical “pact with the Devil” film, and it’s no spoiler to say, this goes as well for the pactee, as these things usually do. However, it’s worth remembering that at the time this was made, France had been conquered by the Nazis. Vichy France was basically a pact with the Devil in political form, and you can certainly read this film, with its range of characters, as an allegory for the contemporary state of the nation. For example, the framing device takes place in an Alpine hotel cut off by an avalanche, a metaphor for France’s isolated state. To this end, the man in charge of the inn is called Denis, the name of one of the country’s (many – Wikipedia lists eleven!) patron saints.

This is, on one level, your typical “pact with the Devil” film, and it’s no spoiler to say, this goes as well for the pactee, as these things usually do. However, it’s worth remembering that at the time this was made, France had been conquered by the Nazis. Vichy France was basically a pact with the Devil in political form, and you can certainly read this film, with its range of characters, as an allegory for the contemporary state of the nation. For example, the framing device takes place in an Alpine hotel cut off by an avalanche, a metaphor for France’s isolated state. To this end, the man in charge of the inn is called Denis, the name of one of the country’s (many – Wikipedia lists eleven!) patron saints.

Unexpectedly arriving there is artist Roland Brissot (Fresnay), who shows up with a small casket, and without his left hand. The curiosity of the other guests is piqued, and Roland tells his story, in a flashback which occupies the bulk of the movie. He was a struggling artist in Paris until buying a talisman from successful chef Mélisse (Roquevert): a severed hand. Roland is warned that he needs to sell the talisman before he dies, for less than he paid for it, or he will spend eternity in hell. It’s not long until Brissot is the talk of the town – albeit painting with his left hand, and signing the paintings ‘Maximus Leo’. The puzzle of who that is, and Roland’s problems in getting rid of the talisman before its curse comes into effect, are central to the rest of the movie.

It takes a little while to find its stride, in part because his girlfriend and eventual wife, Irene (Gaël) is a bit of a bitch. Her interest in him is strictly proportional to his fame and wealth. Interestingly, the actress was having an affair at the time with a Gestapo officer, Antonin Saunier. She was tried for her collaboration after the war, and found guilty of l’indignité nationale. Pact with the Devil, again. Things perk up considerably after the man himself (Palau) shows up, scrutinizing the soul he’s going to get on Roland’s death. This incarnation of Satan is a little old man in a suit and bowler hat, with Palau all the more memorable for his everyday appearance and charming nature, belying his malicious scheming and manipulation.

He offers to let Brissot sell the talisman back to him – but the price will double every day. By the time the artist has made a decision, the cost is at his limit, and the Devil ensures it keeps increasing. Roland loses his wealth and his wife, while his sanity is on increasingly thin ice, after a last, futile, casino-based effort to get the necessary funds ends in failure on the French Riviera. There, he meets all the previous owners – or their ghosts, anyway – of the talisman, all masked and missing a hand (below). He discovers who Maximus Leo was, and finds a loophole that might just allow him to escape perpetual damnation. Which is how Brissot ends up in the mountain inn.

On the one hand, it’s a fairly straightforward telling of the Faustian legend. In its morality, this is not dissimilar to The Picture of Dorian Gray. Someone makes a deal with dark forces, and coming to regret their choice, after initially reaping the rewards. However, I think moving this into a contemporary setting (it was based on a short story by Gérard de Nerval, written over a century prior to the film) works very well. That’s especially true against the wartime background, which gives this considerably more wallop, for the reasons noted above. I’m quite surprised the occupation forces didn’t notice the sentiment; the film seems to have been released without trouble from Nazi censors.

On the one hand, it’s a fairly straightforward telling of the Faustian legend. In its morality, this is not dissimilar to The Picture of Dorian Gray. Someone makes a deal with dark forces, and coming to regret their choice, after initially reaping the rewards. However, I think moving this into a contemporary setting (it was based on a short story by Gérard de Nerval, written over a century prior to the film) works very well. That’s especially true against the wartime background, which gives this considerably more wallop, for the reasons noted above. I’m quite surprised the occupation forces didn’t notice the sentiment; the film seems to have been released without trouble from Nazi censors.

Obviously, the horror is going to be of the implied kind, but Mélisse commanding the severed hand to do tricks, certainly caused mild to moderate goosebumps. Another plus is Palau’s depiction, which is one of the best I’ve seen of the Prince of Lies, precisely because the evil in completely underplayed. He’s a very plausible Satan, with everything he says making sense, especially to the increasingly desperate Brissot. The backdrop may have changed, yet the central narrative is still very much relevant, and this one doesn’t feel over eighty years old at all.

This article is part of our October 2025 feature, 31 Days of Vintage Horror.