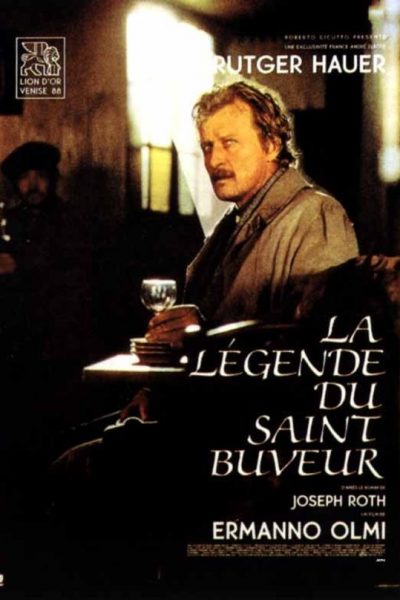

Rating: B-

Dir: Ermanno Olmi

Star: Rutger Hauer, Sandrine Dumas, Dominique Pinon, Anthony Quayle

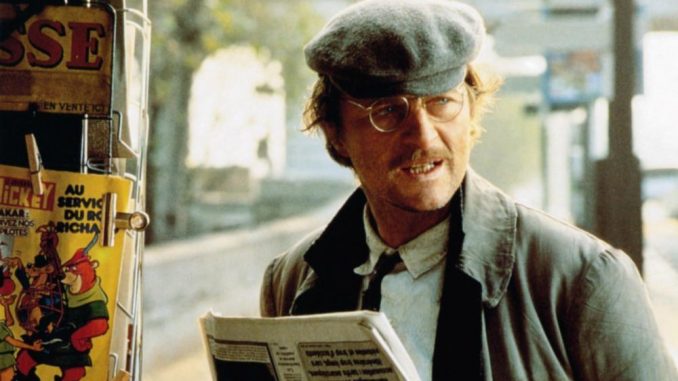

If ever there were a case of magically creating something from nothing, this would be it. Because despite containing very little actual content – it could easily have been a short film, hardly more than a tenth of its actual running-time of 127 minutes – this has an almost hypnotic appeal, due entirely to Hauer’s performance. He plays Andreas, a homeless man living under the bridges of Paris in some vague earlier age . One day, he is given 200 francs by an elderly man (Quayle), who wants Andreas, when he can, to pay back the donation at a nearby church. However, life keeps interfering: more than once, Andreas is literally on the doorstep of the church when he is diverted. Yet life also keeps giving him further opportunities to fulfill his promise. That’s something he wants do, for he is nothing if not honourable, despite having fallen on hard times.

It’s all very laid-back, Andreas drifting through life’s stream, and enduring the snakes and ladders on which he lands with stoicism. We gradually learn about his past, in a series of flashbacks, though even these are more like jigsaw pieces, which a viewer needs to assemble. Best as I can figure: He was a miner in Silesia, who had an affair and accidentally killed her husband, necessitating a quick exit. That’s how ended up in Paris, but a fondness for drink and loose women helped cause his downfall. That’s where we join him, and it’s the gentlest of roller-coaster rides. He gets a temporary job. He meets his old lover (Pinon). He finds money in a wallet. He encounters old friends. He falls for a cabaret dancer (Pinon). He gets given someone else’s wallet. And he drinks. A lot. If you’re looking for thrills of even the mildest kind, you’re definitely in the wrong place. It doesn’t help that the soundtrack is largely Stravinsky, and appears to have been plugged in from another movie.

Yet it’s all rather more affecting than it seems, even if some scenes appear to serve little or no point (or, more likely, their point is so obtuse as to be entirely impenetrable). Olmi knows Hauer is the focus, and often just points the camera at his face, letting his actor’s expression put over the necessary emotions, rather than using words. It’s easy to understand why Rutger felt this was one of his favourite performances; he wasn’t usually given so much room, purely to act. It also helps that the film takes place in a dreamlike, largely uninhabited version of Paris, beautifully captured by Dante Spinotti, who enhances the atmosphere significantly. It’s probably the kind of movie that lingers, rather than making an immediate impression; one you’re more likely to find popping into your thoughts over the days to come. I still wouldn’t say the two-plus hours exactly flew past, yet I remained awake and interested; that’s more than can be said for some, conventionally “exciting” films.

Yet it’s all rather more affecting than it seems, even if some scenes appear to serve little or no point (or, more likely, their point is so obtuse as to be entirely impenetrable). Olmi knows Hauer is the focus, and often just points the camera at his face, letting his actor’s expression put over the necessary emotions, rather than using words. It’s easy to understand why Rutger felt this was one of his favourite performances; he wasn’t usually given so much room, purely to act. It also helps that the film takes place in a dreamlike, largely uninhabited version of Paris, beautifully captured by Dante Spinotti, who enhances the atmosphere significantly. It’s probably the kind of movie that lingers, rather than making an immediate impression; one you’re more likely to find popping into your thoughts over the days to come. I still wouldn’t say the two-plus hours exactly flew past, yet I remained awake and interested; that’s more than can be said for some, conventionally “exciting” films.

Original review [from TC 3]. Hauer should be well known to readers, for his performances as a psychopath in The Hitcher, a barely-controlled psychopath in Wanted: Dead or Alive and a psychopath (medieval variety) in Flesh and Blood. Although always near-perfect, he never seemed to be out of second gear which made the prospect of him playing a down-and-out an intriguing one. Set in Paris, he is given 200 francs by a mysterious stranger (Quayle) with the request to pay it back to a church when he can. Unfortunately, he keeps meeting figures from his past who distract him from this goal and gradually tell us about his earlier life.

With no ‘action’ and almost no plot, the film relies heavily on Hauer, with him rarely being off the screen, so it’s a good job he’s up to the task. He seems very aware of the risk of over-acting, especially in a character of few words as he has here indeed, if anything he’s too subtle, making the viewer concentrate to avoid missing the gestures and looks without which some scenes are meaningless. Olmi shows us a different side to Paris from that normally filmed. Overall, perhaps the best tribute is to say that from now on, when I see Rutger Hauer, I’ll no longer automatically expect him to pull out a shot-gun and start blasting!