During the course of this year’s 31 Days of Vintage Horror, we bumped into various films which, for one reason or another, did not get included in the body of the main feature. However, they were deemed of enough interest to become an appendix to that feature. Therefore, reviews of these five films can be found below. They haven’t received quite the same length of reviews as the main feature, but there’s something to be said for all of them. Even if that something is “not as good as I hoped”!

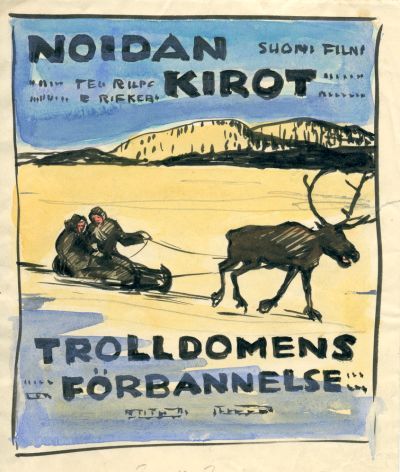

Curses of the Witch (1927)

Rating: C+

Dir: Teuvo Puro

Star: Einar Rinne, Heidi Blåfield, Irmeli Viherjuuri, Kaisa Leppänen

This is believed to be Finland’s first locally produced horror movie, though some say that honour deserves to go to The Old Baron of Rautakylä, made four years earlier, qualifying as Gothic horror. Like most of these proto-genre efforts, you would need to squint a bit to see any connection to what we now know as horror. The witch in question is actually male, going by the name of Jantukka, and when he was captured and killed by a mob of angry villagers for practicing his craft, he laid down a curse of blindness on whoever occupied his lands. Generations later, that still seems to be in effect, with Elsa (Leppänen) afflicted by it. Though its impact thereafter is arguable: the ill events are very human.

Elsa is joined in the remote farmstead where she lives, by her brother, Simo (Rinne) and his new bride Selma (Blåfield), though he soon has to leave them to work. While he is gone, Selma goes out onto the lake to check their fishing nets, and is attacked by a leering lumberjack (the charmingly-named Fat Sakari) and, apparently, raped. Though this being the twenties, we just see her being chased ashore and off into the woods before the screen fades to black, and her husband’s sleep is tormented by a bizarre, demon-like visitor (top). I will say, the use of tinting in this movie is on point, going from almost blood red during the attack on Selma, to chilly blue for Simo’s dream. For a black-and-white film, it’s all surprisingly colourful.

As well as Simo’s night terror and the witch’s curse, there are certainly dark elements, of revenge and familial loss in particular. He blames the curse for Selma’s post-traumatic stress, and she suspects him of involvement in the drowning death of their child, the product of the assault. Though Simo does not suspect it, until the similarity of “his” son to Fat Sakari are brought to his attention. Yeah, even at this early stage, Finnish cinema was living up to its contemporary reputation for gloom ‘n’ doom. However, it is all quite languid. If you’re hoping for a satisfactory helping of Scandinavian payback, you’ll be particularly disappointed, with Simo deciding to be the better man, and let legal justice prevail over vengeance.

As well as Simo’s night terror and the witch’s curse, there are certainly dark elements, of revenge and familial loss in particular. He blames the curse for Selma’s post-traumatic stress, and she suspects him of involvement in the drowning death of their child, the product of the assault. Though Simo does not suspect it, until the similarity of “his” son to Fat Sakari are brought to his attention. Yeah, even at this early stage, Finnish cinema was living up to its contemporary reputation for gloom ‘n’ doom. However, it is all quite languid. If you’re hoping for a satisfactory helping of Scandinavian payback, you’ll be particularly disappointed, with Simo deciding to be the better man, and let legal justice prevail over vengeance.

On the other hand, there is the lovely line: “Well, he’s been stabbed almost every year, but he hasn’t been done away with yet.” Could anything be more Finnish than that? You will see a good deal of lovely Scandinavian scenery, and it helps that the print I watched was in excellent shape, for a film almost one hundred years old. Although, oddly, it has no soundtrack at all – as with most silent films, I feel the accompanying music is a crucial element, to a greater degree than for movies with dialogue. It remains a solid film: while “horror” is a stretch, no more so than for many genre-adjacent entries coming out of other countries, and this is never less than a pleasure to look at.

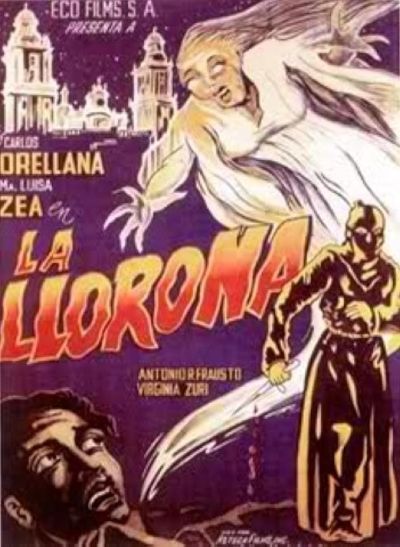

La Llorona (1933)

Rating: D

Dir: Ramón Peón

Star: Ramón Pereda, Virginia Zurí, Carlos Orellana, Adriana Lamar

The first sound horror film to come out of Mexico, and… Yeah, to be honest, I feel we’d have been better off if this one had been lost in the mists of time. By this time, Hollywood had already made the likes of Frankenstein and Freaks. Heck, this came out a couple of months after King Kong had terrorized American audiences. The difference compared to this is palpable; it very much feels like a plodding, amateur production, with some occasionally decent technical elements, but absolutely terrible pacing. For a film which runs a mere seventy minutes to drag as badly as this, takes some effort. There’s only so much children’s birthday party footage I can stand, y’know.

We have covered movies based on the popular Hispanic legend of La Llorona before, so I won’t rehash the basics there. This takes the basic concept – pissed-off woman kills herself and her child, then is doomed to haunt other families – and moves its origins from an indigenous setting to the conqusitadors in the sixteenth century. Viceroy Rodrigo de Cortés spurns his mistress Ana Xiconténcatl (Lamar) who has born his child, and in a fit of righteous anger, she stabs the child dead and then herself. If only the film was as tersely efficient as that sentence. Instead, it’s a meandering story involving another man, Captain Diego de Acuña (Pereda), a wedding which seems to take place in real time, and far too many thoroughly unconvincing sword-fights.

This is all told in an extended flashback, as a story read from a book to Diego’s descendant, Dr. Ricardo de Acuña (also Pereda) by his grandfather. Ricardo’s son Juanito has just celebrated – at greatly unnecessary length – his fourth birthday, and he learns that there’s a family curse, with kids of that age getting stabbed to death. There’s a hooded figure listening as the saga is told, and to my complete lack of surprise, the figure then starts trying to kidnap Juanito. However, it turns out there is a second book, which tells a completely different version of events, in another extended flashback. It turns out the hooded figure is… Well, someone who might have got away with it, if it hadn’t been for you meddling kids.

This is all told in an extended flashback, as a story read from a book to Diego’s descendant, Dr. Ricardo de Acuña (also Pereda) by his grandfather. Ricardo’s son Juanito has just celebrated – at greatly unnecessary length – his fourth birthday, and he learns that there’s a family curse, with kids of that age getting stabbed to death. There’s a hooded figure listening as the saga is told, and to my complete lack of surprise, the figure then starts trying to kidnap Juanito. However, it turns out there is a second book, which tells a completely different version of events, in another extended flashback. It turns out the hooded figure is… Well, someone who might have got away with it, if it hadn’t been for you meddling kids.

Yeah, that’s about the level of plotting we get here, and it’s painfully clear that we are back in the days of “Keep banging the rocks together, guys” era of sound cinema. Outside of the screeching of the ghost, this could well have been a silent film, and certainly does nothing to take advantage of the newfangled technology. The only moment I felt made any real impression was the ghost separating from the body and flying off, which is done fairly well for the time. But the performances don’t bring any urgency to the perilous situations in which the de Acuña family find themselves, and I found myself increasingly unable to care much. If you’re not a fan of the era, this certainly won’t convert you.

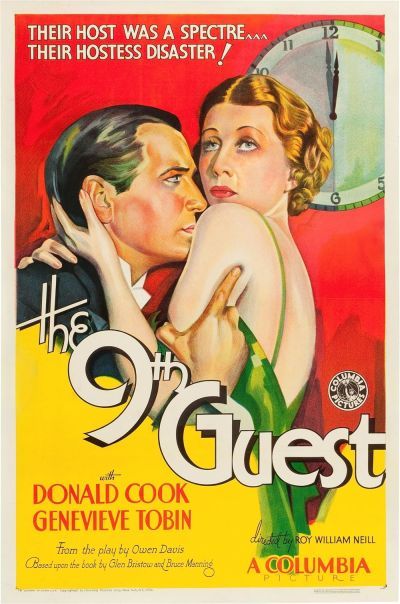

The 9th Guest (1934)

Rating: C+

Dir: Roy William Neill

Star: Donald Cook, Genevieve Tobin, Hardie Albright, Edward Ellis

The concept of a group of people in a confined location, being picked off one by one, by persons unknown, is not a new one. Many people would trace its origins to a certain, unfortunately named Agatha Christie novel of 1939, subsequently published with a less incendiary title, And Then There Were None. But this movie indicates that Christie certainly didn’t invent the idea wholesale. Indeed, one wonders whether she lifted the core idea for her book from this movie. The film was itself based on a Broadway play of the same name, from the start of the decade, which was an adaptation of a 1930 novel, The Invisible Host by husband and wife authors, Bruce Manning and Gwen Bristow.

In this, eight members of New Orleans society are invited by telegram to a party in the penthouse of a building. They generally know each other, or at least of each other, and are not on good terms. The guests include recently fired campus teacher Henry Abbott (Albright), his girlfriend Jean Trent (Tobin), writer James Daley (Cook) and District Attorney Tim Cronin (Ellis), as well as mob boss Jason Osgood and socialite Margaret Chisholm. A voice on the radio introduces himself as the unknown host, and tells them there will be a ninth guest: “His name is death.” Naturally, it’s not long before the attendees are being thinned out – beginning with Osgood who is poisoned after cutting himself on a bottle of cyanide.

It’s all reasonably nicely constructed, and of course, this kind of thing was a lot easier to do in the thirties. Now, someone would whip out their cellphone and that’d be it. Here, cutting the sole phone-line is enough. Well, along with electrifying the exit, which leads to one of the deaths: it’s rather nasty for the time, the victim’s scream in particular quite chilling the blood as the current courses through their body in a shower of sparks. Sadly, there’s nothing in the rest of the film which has as much impact. Part of the problem is that the characters are largely not very likeable, being mostly upper-class types, from a time when class was a sharp divider in American society.

It’s all reasonably nicely constructed, and of course, this kind of thing was a lot easier to do in the thirties. Now, someone would whip out their cellphone and that’d be it. Here, cutting the sole phone-line is enough. Well, along with electrifying the exit, which leads to one of the deaths: it’s rather nasty for the time, the victim’s scream in particular quite chilling the blood as the current courses through their body in a shower of sparks. Sadly, there’s nothing in the rest of the film which has as much impact. Part of the problem is that the characters are largely not very likeable, being mostly upper-class types, from a time when class was a sharp divider in American society.

The eventual solution is moderately interesting exercise, involving advanced technology such as an auto-changing phonograph. This aspect would certainly be easier for any budding psychopath to manage these days, with an iPhone and Bluetooth-enabled speakers, so perhaps a remake could be arranged. There is scope for improvement in a number of ways, with the killer’s motive feeling a little light, in terms of the mass murder which results. Trying to introduce the eight characters also takes up too much time, in a film lasting only seventy minutes. I’d have started in the penthouse, brought them in from there, and let their interactions reveal their connections and personas. It’s notable more for its influence, as an early example of the whodunnit in cinema.

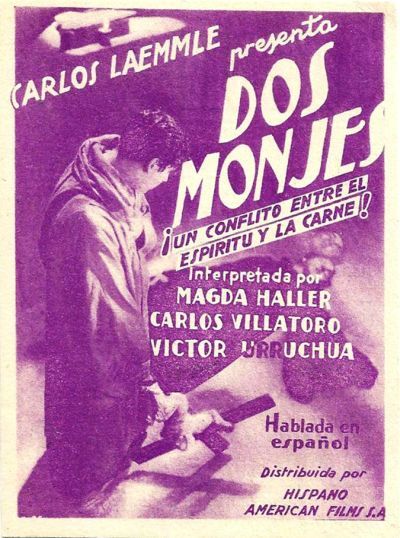

Two Monks (1934)

Rating: C+

Dir: Juan Bustillo Oro

Star: Víctor Urruchúa, Carlos Villatoro, Magda Haller, Beltrán de Heredia

a.k.a. Dos monjes

This has strong bookend sections and a film that is certainly ahead of its time in a number of ways. However, this isn’t able to conceal the basically banal nature of the central plot, a boring and tepid love triangle. We begin in a monastery where new monk Juan (Urruchúa) is asked to tend to the troubled Javier (Villatoro), only to be knocked unconscious with a crucifix for his pains. The prior (de Heredia) quizzes both men separately, to get to the bottom of things, and discovers there was previous history between them. Specifically, they were rivals for the love of Ana (Haller), before an incident in which she was shot dead.

Element ahead of its time, #1. We get to experience that story, first from Javier’s perspective, then Juan’s. This was sixteen years before Kurosawa’s Rashomon became the go-to example of an incident told from more than one perspective. Here, the approach is relatively rough in approach, yet Oro has some good flourishes. For example, when Juan tells his story, he is dressed in white as the hero, with the villainous Javier clad in black. When Javier describes his version, the costume tones are reversed. Unfortunately, it’s not enough to sustain a story which had difficulty keeping my attention once, never mind twice. It’s also surprisingly… gay for thirties Mexico. While I usually notice little and care less, at times I wondered if this love triangle should be tinted pink, shall we say.

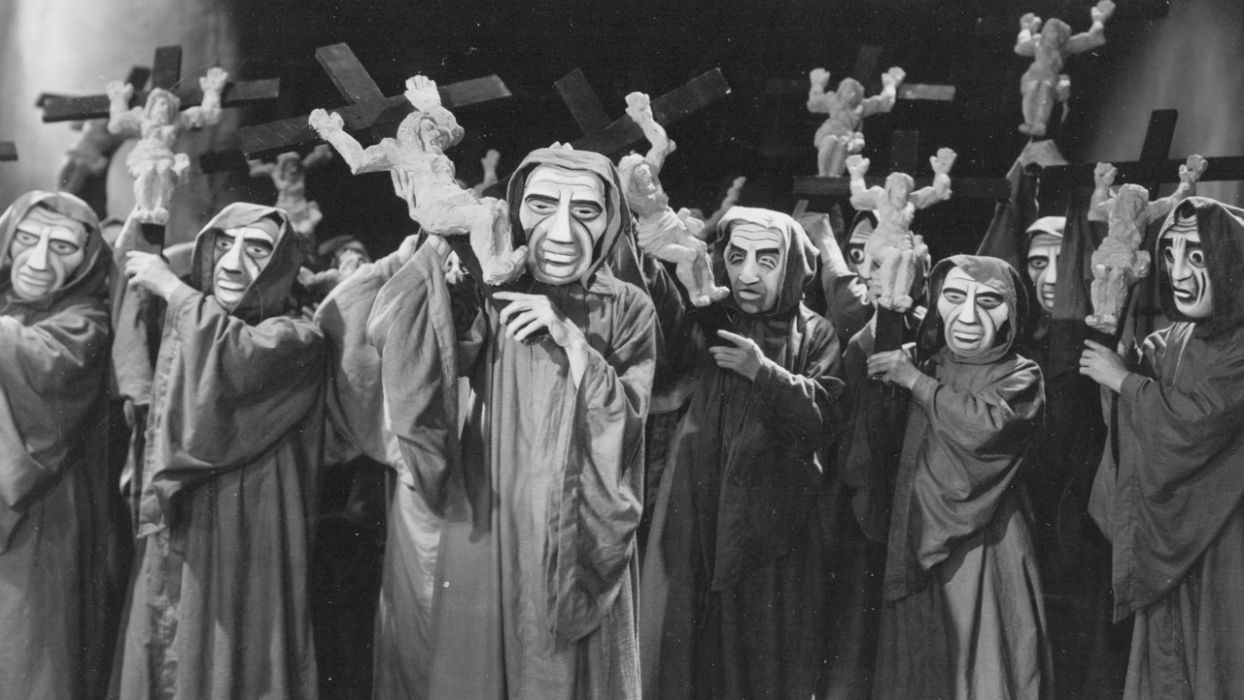

Element ahead of its time, #2. The visual style – especially, though not uniquely, around the monastery. Though it may not be ahead of its time so much as radically different. For if you showed me a still and told me this came out of Germany in the twenties, I’d have believed you, for this is, I guess, Mexican Expressionist cinema. Oro has a fine eye for it, especially towards the end when one of our protagonists goes a bit nuts, engaging in rampant, uncontrolled organ-playing, before hallucinating his fellow friars are monsters out to kill him (top). I’d have like to have seen more of this weirdness, along with the “possession in a monastery” angle, and less romantic melodrama.

Element ahead of its time, #2. The visual style – especially, though not uniquely, around the monastery. Though it may not be ahead of its time so much as radically different. For if you showed me a still and told me this came out of Germany in the twenties, I’d have believed you, for this is, I guess, Mexican Expressionist cinema. Oro has a fine eye for it, especially towards the end when one of our protagonists goes a bit nuts, engaging in rampant, uncontrolled organ-playing, before hallucinating his fellow friars are monsters out to kill him (top). I’d have like to have seen more of this weirdness, along with the “possession in a monastery” angle, and less romantic melodrama.

The latter does have its moments, such as before Javier and Ana are a thing, and he’s watching her interact with a suitor her family has brought in. This takes place entirely in silhouette, and is striking. But, between his song composition and consumption, Javier in particular is such a wuss as to resemble a pre-war, Hispanic version of Morrissey. Dios sabe que ahora soy miserable. So who shot Ana? The film never comes to any particular conclusion, and I suspect the director was considerably more interested in the journey than the destination. Though my money is on the loony one. Even at the time, the love story was considered “over-romantic and flamboyant.” Time has likely not done that aspect many favours.

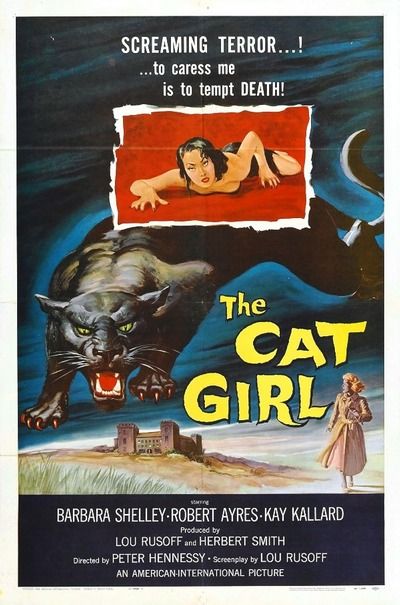

Cat Girl (1957)

Rating: C

Dir: Alfred Shaughnessy

Star: Barbara Shelley, Robert Ayres, Kay Callard, Jack May

This is proof that mockbusters were not invented by The Asylum. Coming out almost fifteen years after Cat People, it can hardly be accused of being a quick cash-in, at the very least. The similarities are undeniable, however. Leonora Johnson (Shelley) gets a summons from her uncle to his remote country estate. She’s supposed to go alone, but brings her husband, Richard (May), and a couple of friends for moral support. While this displeases her uncle, he reveals she’s the next in line for the family curse. This has her being possessed by the spirit of a leopard, which comes out, in a violent fashion, when her passions are inflamed

And that’s a lot. Because at her uncle’s, she meets old flame Brian Marlowe (Ayres), who is now a psychiatrist. He is married to Dorothy (Callard), but it’s okay, because Richard is cheating on Leonora anyway, with her friend. Well, until their tryst gets interrupted by a leopard attack. This is not normal for rural England, to put it mildly. Leonora, having initially dismissed her uncle’s talk of a family curse, begins to think there might be something to it. Brian, on the other hand, thinks her belief is nonsense, and just the symptom of a mental disorder. Despite his scepticism, reports of a roaming leopard persist, and the relationship between Leonora and Dorothy grows steadily chillier. The mental state of the former woman is also deteriorating. I mean, she starts smoking… (top).

The best thing about this, by quite some way, is Shelley. Though she’d appeared in some minor roles before (such as 1953 Hammer production, Mantrap), this was her first after returning from a four-year spell working in Italy. She would deservedly go on to become one of the most prominent British “scream queens” of the sixties, including appearances in The Gorgon and Quatermass and the Pit. Here, she grounds the film and gives it an emotional heart, in a way Simone Simon could not manage. In every other way though, this isn’t as good. Part of the problem is, it can’t decide if the leopard is Leonora, a physical manifestation of her emotions, or what. I still didn’t know after the movie ended.

The best thing about this, by quite some way, is Shelley. Though she’d appeared in some minor roles before (such as 1953 Hammer production, Mantrap), this was her first after returning from a four-year spell working in Italy. She would deservedly go on to become one of the most prominent British “scream queens” of the sixties, including appearances in The Gorgon and Quatermass and the Pit. Here, she grounds the film and gives it an emotional heart, in a way Simone Simon could not manage. In every other way though, this isn’t as good. Part of the problem is, it can’t decide if the leopard is Leonora, a physical manifestation of her emotions, or what. I still didn’t know after the movie ended.

It seems the writer, Lou Rusoff, the director, and co-producers American International Pictures, all had different ideas for the film. Shaughnessy wanted to take a psychological approach, but AIP’s Samuel Z. Arkoff reportedly said, “Where is the cat monster?” on seeing an initial cut, and had a cat mask made in three days to splice into the US print. Rusoff, meanwhile, didn’t care, so long as he got paid for his script. The results suggest he might have had the most reasonable approach. The awkward nature of the US/UK co-production (with Anglo-Amalgamated, who did a lot of the early Carry On films, hence Peter Rogers’ name in the end credits) shows up in things like Ayres’ American accent. My advice? Pick a side of the Atlantic and stick with it.