I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.

Time to die.

For most people, Hauer is best-known for his role as the replicant, Roy Batty, in Blade Runner. That’s understandable, with the “Tears in rain” monologue one of the most iconic speeches in the SF genre – a field more noted for visual spectacle than word pictures. Rutger not only delivered it perfectly, he was also heavily involved in its creation, though it wasn’t the improvisation sometimes claimed by the legend which has grown around it. A legend which will likely only increase with the realization Roy Batty and Hauer both died in 2019, that being the year in which Blade Runner was set.

More importantly, it was only a fraction of Hauer’s talents, which spanned the entire spectrum of cinema from big-budget genre blockbusters to independent dramas. It would be a stretch to say every movie he was in was great, or even good. He certainly had his share of clunkers, films which even Hauer’s talents were not able to salvage. But he was no less than good in everything he was in, and often great.

He was one of the few actors who could play both hero and villain, as well as anywhere in the middle, and be equally effective. Good guy? Blind Fury, Ladyhawke or Wedlock. Bad guy? Nighthawks, Surviving the Game or Dracula III [sidenote: Hauer must be one of the few actors to ever play both Dracula and Abraham Van Helsing, portraying the latter in Dario Argento’s Dracula 3-D]. But even his antagonists were more than cardboard caricatures of mustache-twirling evil. They had a wit and a charm which made them appealing, such was his charisma.

His talent and success in Hollywood was all the more remarkable, considering Dutch was his first language, and he didn’t make his English-speaking debut until Rutger was in his thirties. In this way, he felt a bit like this generation’s version of Klaus Kinski – albeit without any of the attached baggage! For even befoire his death, you’d be hard-pushed to find anyone with a bad word to say about Hauer. He was with the same woman, painter Ineke ten Kate, for over fifty years, and worked tireless on behalf of the Starfish Association, the HIV charity he founded.

And finally, he’s the reason Guinness was my drink of choice in the years after I graduated from university in 1987. Chosen partly because of his resemblance to a pint of the stuff (seriously), Hauer was involved in the beer’s advertising for eight years, creating an array of weird, wonderful and surreal adverts we still quote to this day (the “nipples like bullets” line, for example). They were so impressive, I started drinking the product – and, let’s just say, Guinness probably counts as an acquired taste, so there was effort involved! Tonight, I’ll raise a glass of it in honour of Mr. Hauer, and all the pleasure his talents gave me over the decades. It’s not easy being a dolphin…

Below you’ll find reviews of five of his most memorable non-Blade Runner roles, covering Hauer’s career from the early days in Holland, through mainstream success and out the other side. I’ve also included my thoughts at the time they were first reviewed.

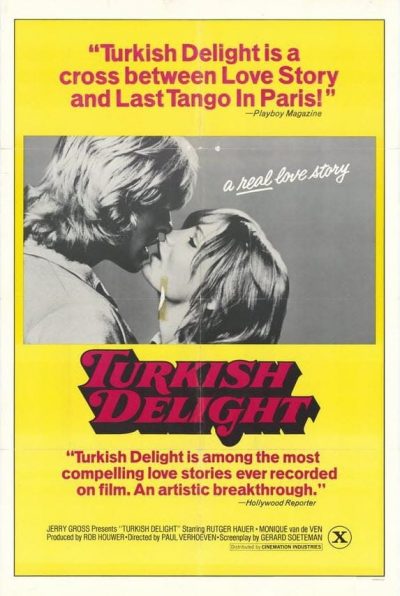

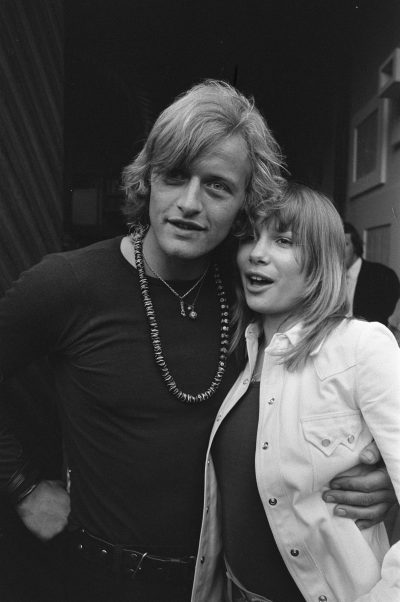

Turkish Delight (1973)

Rating: B

Dir: Paul Verhoeven

Star: Rutger Hauer, Monique van de Ven, Wim van den Brink, Tonny Huurdeman

a.k.a. Turks Fruit

This was very much a breakthrough feature for Verhoeven, who had worked previously with Hauer on the hit TV series, Floris, best described as a Dutch version of Robin Hood. Though originally aimed at children, it was appreciated by adults as well – but could hardly have been more different from this. For what you have is an earthy, to the point of raunchy, love-story between Eric (Hauer), a sculptor, and Olga (van de Ven), the daughter of a well-to-do store owner. Much of it is told in flashback: we initially see Eric in the aftermath of their break-up, when he is engaging in serial promiscuity and vague misogyny as a reaction to his loss, as well as having violent fantasies of revenge [similar to the protagonist in The Fourth Man, a subsequent Verhoeven movie].

We then go back to two years previously, when she picks him up hitch-hiking. Thus begins a passionate affair, which initially draws the disapproval of her mother (Huurdeman), though her more easy-going father (van den Brink) is far less bothered by him. Still, they eventually get married – apparently, in the Netherlands, group weddings involving multiple couples at once are a thing. Maybe you get a discount for bulk? Anyway, the sheer energy of their relationship cannot be sustained forever; the light that burns twice as bright, burns half as long, perhaps? Her increasingly erratic actions, coupled with his jealousy, eventually leads to a split. Though fate is not quote finished with the couple, bringing them back together into each other’s lives.

It’s very definitely a product of its times, when free love was the defining element of the era for some, with women’s liberation still trying to figure itself out. Let’s be honest: Eric comes over as a bit rapey, though judging the film by 2019’s #MeToo standards is a ludicrous concept. Yet the fresh-faced Hauer possesses a charisma which makes it easy to see why women fall for his schtick in droves. However, there’s no doubt he also cares about Olga deeply, even if his refusal to compromise is a significant factor in what drives them apart. It is complicated, messy and there are no heroes or villains to be found here. In other words, it’s just like real life, and impressively grounded, despite all the societal changes over the ensuing four decades.

It’s very definitely a product of its times, when free love was the defining element of the era for some, with women’s liberation still trying to figure itself out. Let’s be honest: Eric comes over as a bit rapey, though judging the film by 2019’s #MeToo standards is a ludicrous concept. Yet the fresh-faced Hauer possesses a charisma which makes it easy to see why women fall for his schtick in droves. However, there’s no doubt he also cares about Olga deeply, even if his refusal to compromise is a significant factor in what drives them apart. It is complicated, messy and there are no heroes or villains to be found here. In other words, it’s just like real life, and impressively grounded, despite all the societal changes over the ensuing four decades.

This remains the most successful film in Dutch cinema, being seen on its release by a number equivalent to about a quarter of the nation’s population at the time. There are some elements which perhaps have lost their meaning through the haze of time, such as the elements of social satire. For example, an interlude where the Queen of the Netherlands shows up to unveil one of Eric’s statues has no punch, and showcases Verhoeven’s lack of comedic sensibilities. But the darkness which bookends this is both unexpected and effective. As the poster (right) suggests, the film demonstrates the marked difference between this and Hollywood saccharine like Love Story, not dissimilar in theme and released three years previously.

Original review. Deja vu. Going by the cast and crew list on this one, you could be forgiven for thinking you’ve seen – or at least read about – this before. Hauer, Van De Ven, Verhoeven and De Bont all make a re-appearance, together with frequent Verhoeven scriptwriter, Gerard Soeteman. Hauer’s character, the appropriately named Eric Bonk, also seems straight out of Dandelions, a serial woman-hater for whom a one-night stand is a long-term relationship. In this case, however, rather than a quest for perfection, it’s down to events in his past, flashbacks to which occupy the majority of the movie.

Original review. Deja vu. Going by the cast and crew list on this one, you could be forgiven for thinking you’ve seen – or at least read about – this before. Hauer, Van De Ven, Verhoeven and De Bont all make a re-appearance, together with frequent Verhoeven scriptwriter, Gerard Soeteman. Hauer’s character, the appropriately named Eric Bonk, also seems straight out of Dandelions, a serial woman-hater for whom a one-night stand is a long-term relationship. In this case, however, rather than a quest for perfection, it’s down to events in his past, flashbacks to which occupy the majority of the movie.

This kind of role suits Hauer down to the ground, and Verhoeven seems better able to handle the ensuing emotional intensity than Adrian Hoven manages. It’s irregularly amusing, with Hauer’s wild character causing chaos in a variety of forms (for example, one of which involves a statue, a dress that won’t stay up, and the queen of the Netherlands!), and all supporting roles are solidly presented. At first, the new love he’s found seems ideal for him, but the flashback structure means we know it’s doomed to failure – the only questions are how and when. It manages to avoid too much of the classic 70’s style, so unerringly hit by Dandelions, and is worth a look; it’s now out on sell through, unashamedly trading on both star and director’s subsequent careers! C+

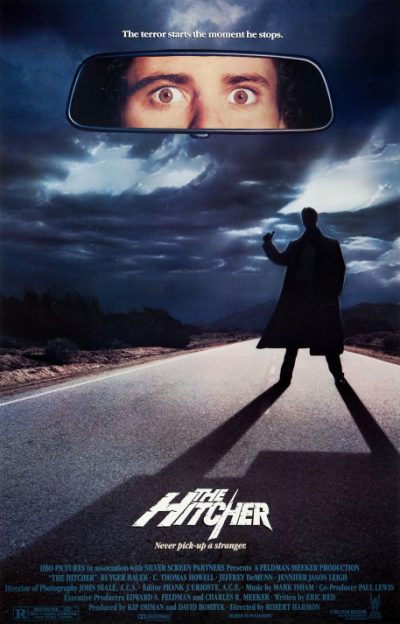

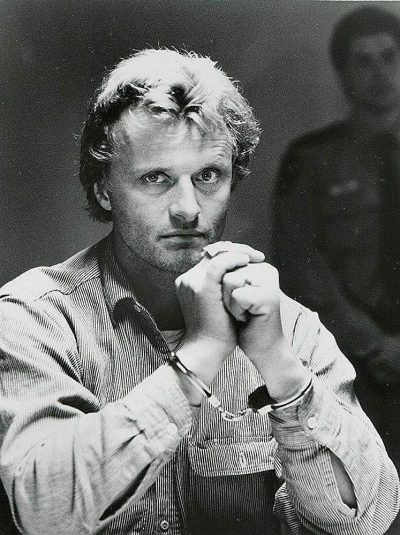

The Hitcher (1986)

Rating: A

Dir: Robert Harmon

Star: C. Thomas Howell, Rutger Hauer, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Jeffrey DeMunn

Chris showed this movie to her teenage daughters, in order to scare them off hitch-hiking. While, technically, more a warning about the dangers of picking up hitch-hikers, it seemed to have worked, and it’s easy to understand why. Jim Halsey (Howell) has a job driving a car from Chicago to San Diego. In danger of falling asleep late one night, on a lonely highway in Tezas, he picks up John Ryder (Hauer), in an effort to stay asleep, even though he knows it’s a bad idea. “My mother told me never to do this,” is his first line. Cut to Chris nodding, emphatically.

For Mrs. Halsey was absolutely correct. It’s not long before we sense the true nature of Ryder, who makes no attempt to hide it. There’s a quiet, understated certainty about the way he delivers his lines. In less subtle hands, lines like, “Because I cut off his legs… and his arms… and his head. And I’m gonna do the same to you,” could have become the stuff of camp. Here, they’re stated as a laconic matter-of-fact by Hauer, and are all the more impactful as a result. But it’s not long before John starts delivering the terror; even being booted out of the moving car by Jim proves to be only a temporary setback.

It’s very much a product of its time in many ways: the existence of cellphones these days would require significant rewriting. I was also struck by how the three lead characters all smoke, to such a degree I was surprised the hero wasn’t named Philip Morris. There’s also the question of what he’s doing in Texas to begin with. Because, according to Google Maps, the route from Chicago to San Diego goes nowhere near that state. However, explanations are largely deemed irrelevant by the film. For example, none is provided for the supernatural way in which Ryder is perpetually able to remain one step ahead of his victim, e.g. dropping a severed digit into his burger and fries, purely for the LOLs.

It’s very much a product of its time in many ways: the existence of cellphones these days would require significant rewriting. I was also struck by how the three lead characters all smoke, to such a degree I was surprised the hero wasn’t named Philip Morris. There’s also the question of what he’s doing in Texas to begin with. Because, according to Google Maps, the route from Chicago to San Diego goes nowhere near that state. However, explanations are largely deemed irrelevant by the film. For example, none is provided for the supernatural way in which Ryder is perpetually able to remain one step ahead of his victim, e.g. dropping a severed digit into his burger and fries, purely for the LOLs.

Watching it this time, I was surprised to realize how little Hauer’s character is actually on-screen. He’ll dip in, terrorize his victim, then vanish. Yet his presence looms over almost every scene, and drives Jim’s character arc. He gradually turns from a meek kid into someone who, towards the end, bears more than a passing resemblance to a young Mad Max, hunched over the wheel of his deathmobile. He has become a vicious killer, which was John’s intention all along. I tend to view Ryder as Satan, perhaps literally, whose mission is to corrupt his victim. It’s hard to argue with what Hauer said of this character: “To me, the devil can be a piece of foam inside your brain. To me, he was a ghost of sand or something. An unreal character. My job for that film was to make you feel that this man can do really weird shit and even if you don’t see it, you’ll believe he did.”

Finally, spare a thought for the poor owner of the car Jim was driving to San Diego. It was side-swiped by a bus, then set on fire at a gas station, and eventually abandoned at the diner. I’d love to have seen that insurance report.

Original review [March 2009]. I’m still amused by Roger Ebert’s review of this where he wrote, “This movie is diseased and corrupt…it is reprehensible.” He seems obsessed by the homoerotic subtext he sees in the relationship between psychotic John Ryder (Hauer) and Jim Halsey (Howell), as the former stalks, torments and confronts his prey, for no real purpose at all. Occasionally, this seems possible, but it feels more like a father-son relationship [it reminds me of the one in Dexter] and that reading is countered by sequences like the one where Ryder snuggles up to Nash (Leigh), gently stroking her arm. Here’s an interesting thought: Ryder doesn’t actually exist, except as a deranged figment of Halsey’s imagination, a persona separated off to blame for the killings Halsey is actually committing. For we never actually see Ryder kill anyone. Certainly, there are some issues with this reading; though not really any more than, say, Fight Club.

Original review [March 2009]. I’m still amused by Roger Ebert’s review of this where he wrote, “This movie is diseased and corrupt…it is reprehensible.” He seems obsessed by the homoerotic subtext he sees in the relationship between psychotic John Ryder (Hauer) and Jim Halsey (Howell), as the former stalks, torments and confronts his prey, for no real purpose at all. Occasionally, this seems possible, but it feels more like a father-son relationship [it reminds me of the one in Dexter] and that reading is countered by sequences like the one where Ryder snuggles up to Nash (Leigh), gently stroking her arm. Here’s an interesting thought: Ryder doesn’t actually exist, except as a deranged figment of Halsey’s imagination, a persona separated off to blame for the killings Halsey is actually committing. For we never actually see Ryder kill anyone. Certainly, there are some issues with this reading; though not really any more than, say, Fight Club.

This is probably Hauer’s best performance ever, totally dominating the screen, in a way rarely seen, to the point that the rest of the cast struggles to keep up, even Leigh, who has done some fine work since. Here, she ends up on the receiving end of some Rutger-abuse, not for the first time in her career (see also Flesh and Blood), taking part in what we like to call the Jennifer Jason Leigh Taffy Pull. Eric Red’s script does an excellent job of creating a mythical monster, a modern-day boogeyman more threatening than Jason, Freddy or Michael, simply because he possesses no motive. “Why are you doing this?” begs Jim, and gets the impenetrable response, “Because I want you to stop me.” Jim’s question actually applies just as much to the ground up and spat out remake twenty years later, which possessed not one ounce of the danger or suspense shown here. If only someone had stopped that… A-

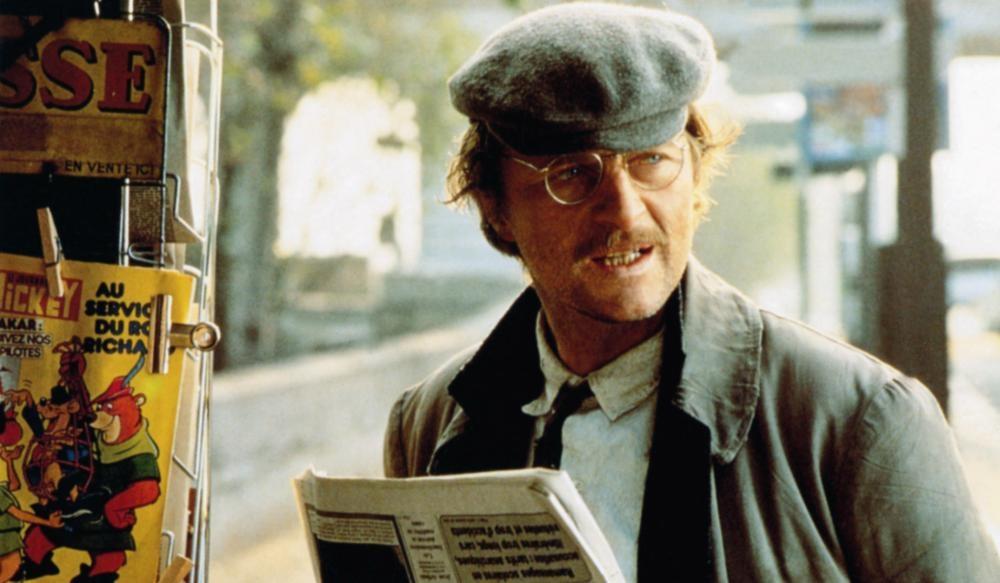

The Legend of the Holy Drinker (1988)

Rating: B-

Dir: Ermanno Olmi

Star: Rutger Hauer, Sandrine Dumas, Dominique Pinon, Anthony Quayle

If ever there were a case of magically creating something from nothing, this would be it. Because despite containing very little actual content – it could easily have been a short film, hardly more than a tenth of its actual running-time of 127 minutes – this has an almost hypnotic appeal, due entirely to Hauer’s performance. He plays Andreas, a homeless man living under the bridges of Paris in some vague earlier age . One day, he is given 200 francs by an elderly man (Quayle), who wants Andreas, when he can, to pay back the donation at a nearby church. However, life keeps interfering: more than once, Andreas is literally on the doorstep of the church when he is diverted. Yet life also keeps giving him further opportunities to fulfill his promise. That’s something he wants do, for he is nothing if not honourable, despite having fallen on hard times.

It’s all very laid-back, Andreas drifting through life’s stream, and enduring the snakes and ladders on which he lands with stoicism. We gradually learn about his past, in a series of flashbacks, though even these are more like jigsaw pieces, which a viewer needs to assemble. Best as I can figure: He was a miner in Silesia, who had an affair and accidentally killed her husband, necessitating a quick exit. That’s how ended up in Paris, but a fondness for drink and loose women helped cause his downfall. That’s where we join him, and it’s the gentlest of roller-coaster rides. He gets a temporary job. He meets his old lover (Pinon). He finds money in a wallet. He encounters old friends. He falls for a cabaret dancer (Pinon). He gets given someone else’s wallet. And he drinks. A lot. If you’re looking for thrills of even the mildest kind, you’re definitely in the wrong place. It doesn’t help that the soundtrack is largely Stravinsky, and appears to have been plugged in from another movie.

Yet it’s all rather more affecting than it seems, even if some scenes appear to serve little or no point (or, more likely, their point is so obtuse as to be entirely impenetrable). Olmi knows Hauer is the focus, and often just points the camera at his face, letting his actor’s expression put over the necessary emotions, rather than using words. It’s easy to understand why Rutger felt this was one of his favourite performances; he wasn’t usually given so much room, purely to act. It also helps that the film takes place in a dreamlike, largely uninhabited version of Paris, beautifully captured by Dante Spinotti, who enhances the atmosphere significantly. It’s probably the kind of movie that lingers, rather than making an immediate impression; one you’re more likely to find popping into your thoughts over the days to come. I still wouldn’t say the two-plus hours exactly flew past, yet I remained awake and interested; that’s more than can be said for some, conventionally “exciting” films.

Yet it’s all rather more affecting than it seems, even if some scenes appear to serve little or no point (or, more likely, their point is so obtuse as to be entirely impenetrable). Olmi knows Hauer is the focus, and often just points the camera at his face, letting his actor’s expression put over the necessary emotions, rather than using words. It’s easy to understand why Rutger felt this was one of his favourite performances; he wasn’t usually given so much room, purely to act. It also helps that the film takes place in a dreamlike, largely uninhabited version of Paris, beautifully captured by Dante Spinotti, who enhances the atmosphere significantly. It’s probably the kind of movie that lingers, rather than making an immediate impression; one you’re more likely to find popping into your thoughts over the days to come. I still wouldn’t say the two-plus hours exactly flew past, yet I remained awake and interested; that’s more than can be said for some, conventionally “exciting” films.

Original review [from TC 3]. Hauer should be well known to readers, for his performances as a psychopath in The Hitcher, a barely-controlled psychopath in Wanted: Dead or Alive and a psychopath (medieval variety) in Flesh and Blood. Although always near-perfect, he never seemed to be out of second gear which made the prospect of him playing a down-and-out an intriguing one. Set in Paris, he is given 200 francs by a mysterious stranger (Quayle) with the request to pay it back to a church when he can. Unfortunately, he keeps meeting figures from his past who distract him from this goal and gradually tell us about his earlier life.

With no ‘action’ and almost no plot, the film relies heavily on Hauer, with him rarely being off the screen, so it’s a good job he’s up to the task. He seems very aware of the risk of over-acting, especially in a character of few words as he has here indeed, if anything he’s too subtle, making the viewer concentrate to avoid missing the gestures and looks without which some scenes are meaningless. Olmi shows us a different side to Paris from that normally filmed. Overall, perhaps the best tribute is to say that from now on, when I see Rutger Hauer, I’ll no longer automatically expect him to pull out a shot-gun and start blasting!

Split Second (1992)

Rating: B

Dir: Tony Maylam

Star: Rutger Hauer, Neil Duncan, Kim Cattrall, Alun Armstrong

A rare appearance by Hauer in a documentary, this depicts everyday life in London, circa 2008. Oh, wait: my mistake. Apparently, by that date, global warming will turn – or had turned, from a current perspective – London into a somewhat flooded den of iniquity. Though if you can’t spot the difference, it’s understandable. Slightly less knife crime in this version, probably.

Hauer plays Harley Stone, a Loose Cannon Cop (TM), haunted by the death of his partner at the hands of a mysterious creature, ten years previously. Though not, apparently, so haunted as to stop him from banging his partner’s wife, Michelle (Cattrall). Harley now survives on a diet of coffee, processed sugar and adrenaline, and matters are not helped by the apparent return of the killer, which resumes its murderous acts. It appears to have some kind of psychic link to Stone, and sends him little presents, such as an ice-chest containing a slightly-chewed heart. Totes adorbs.

In a desperate attempt to rein Harley in, his boss assigns him a new partner, rookie Dick Durkin (Duncan), who is the complete opposite of Stone, naturally: Oxbridge-educated, clean living and intellectual, rather than going by his gut. However, instead of having the intended effect, Durkin is the one changed, particularly after he encounters the monster. All of a sudden, and much to his partner’s joy, he comes over all, “We need bigger guns, big fucking guns! We’re getting big guns, right? That’s where we’re going, to get big guns…”

This story is, obviously, nonsense, as much as its gratuitous use of Nights in White Satin implies. When we finally see the creature, it’s an Alien-knockoff – so, how the hell was it capable of buying and sending a goddamn ice-chest to Harley? It doesn’t even seem to have opposable thumbs. You can certainly tell the original director bailed, with someone else (Ian Sharp) directing the finale, which supposedly takes place on the platform at Cannon Street tube station, and is largely at odds with what has gone before. The method of demise for the creature is particularly questionable, suggesting this monstrous beast has a rib-cage constructed of balsa.

This story is, obviously, nonsense, as much as its gratuitous use of Nights in White Satin implies. When we finally see the creature, it’s an Alien-knockoff – so, how the hell was it capable of buying and sending a goddamn ice-chest to Harley? It doesn’t even seem to have opposable thumbs. You can certainly tell the original director bailed, with someone else (Ian Sharp) directing the finale, which supposedly takes place on the platform at Cannon Street tube station, and is largely at odds with what has gone before. The method of demise for the creature is particularly questionable, suggesting this monstrous beast has a rib-cage constructed of balsa.

And, yet… In my mental library, this gets filed alongside another example of funky, cheap SF from the early nineties, Hardware. I’m not sure why that seems to have a higher cult status. There’s a similarly grungy aesthetic, and both films provide a guest spot for a British musical icon – here, the late Ian Dury as a club-owner. You also have the similarly late Pete Postlethwaite in support, playing a cop a year before his Oscar nomination for In the Name of the Father [Pauses to check if Kim Cattrall is still alive… Yep, we’re good.]

This is one of the cases where Hauer proved capable of lifting questionable material up, through sheer force of will. And credit due to Duncan, for withstanding all of Rutger’s scene-stealing, even if he comes over as a budget version of John Hannah. Their slowly-developing relationship is a joy to watch; Duncan had a long stint as a side-banana on Taggart, and slots into a similar role here very nicely. Meanwhile, despite sounding like a retired WWF wrestler, Harley Stone is one of Hauer’s best characters, and deserves to take his place in the Loose Cannon Cop (TM) Hall of Fame, along John McClane, Martin Riggs and John Spartan.

Original review: This thoroughly enjoyable B-movie stars Hauer as screwed-up cop Harley Stone, who lives on sugar, coffee, adrenalin and irritating his co-workers, particularly his new partner (played by Taggart veteran Duncan). Still, it’s a screwed-up world too, with London knee-deep in water, and an insane serial-killer slaughtering people in ominous fashion. The plot is, by and large, ludicrous: it’s the interplay between Hauer and Duncan that make this work, as the latter’s character slowly warps towards that of his colleague, culminating in the renowned “bigger guns” speech which nods to Jaws while simultaneously eclipsing it. The supporting cast includes Pete Postlethwaite, Ian Dury, Cattrall and Michael J. Pollard – one of them spends a lot of time in the shower, luckily, it’s the one you’d expect. The film also delivers a fair bit of gore, and London is used to good effect. But this is Hauer and Duncan’s movie, without a doubt, and it’s one of the former’s finest outings since The Hitcher. B+

Hobo With a Shotgun (2011)

Rating: A

Dir: Jason Eisener

Star: Rutger Hauer, Molly Dunsworth, Brian Downey, Gregory Smith

I like to think of this as an unofficial remake of Legend of the Holy Drinker, with Hauer again playing a homeless man, whose modest and honest ambitions are perpetually derailed by the hand of fate. Ok, this may be a bit of a stretch. For it is everything Drinker wasn’t, in terms of tone and content: a raucous celebration of cinematic violence and grindhouse morality. That a well-known and critically-acclaimed actor like Hauer signed up for it, tells you a lot. That he is perfect in the title role, giving it equally much in terms of commitment and effort, as less grubby (and certainly better-paid) work, says even more. It’s a genuine shame Eisener – who also made the brilliant psychoflora short, Treevenge – has not apparently directed another feature since.

This is not just a movie which pays tribute to the style of the eighties “video nasties.” That kind of thing is easy to do: throw some faux artifacts onto your film, add in some anachronistic content like rotary phones, maybe a cheesily retro soundtrack and there you go. But what you have here is something which is also a thoroughly fun film on its own – and would have been so, regardless of the style. Hauer makes a great tragic hero; Downey, a fabulously slimy villain, chewing scenery up and spitting it out to great effect. Even Dunsworth takes a role which could have been simply a cliched “hooker with a heart of gold,” and gives it depth. There’s a lovely attention to little details here, which bring out the characters and make them seem larger than life: what could be more Canadian than a bad guy who shows up with ice-skates on?

The same goes for the written elements, both the dialogue, or even the sign the hobo has while panhandling. Saying “Need $ for lawn mower” would be functional – adding “I am tired” at the start, imbues it with a beautiful poignancy, especially given Hauer’s recent passing. There are so many lines here which are quotable… albeit probably not in a work setting… or indeed, most places. But some day, I hope to find an appropriate setting to yell, “I’m gonna sleep in your bloody carcasses tonight!” This reaches its likely peak, in a speech given by the hobo in a hospital to a room of newborn infants. While “tears in rain” may be his most famous monologue, this is surely little less worthy of renown

The same goes for the written elements, both the dialogue, or even the sign the hobo has while panhandling. Saying “Need $ for lawn mower” would be functional – adding “I am tired” at the start, imbues it with a beautiful poignancy, especially given Hauer’s recent passing. There are so many lines here which are quotable… albeit probably not in a work setting… or indeed, most places. But some day, I hope to find an appropriate setting to yell, “I’m gonna sleep in your bloody carcasses tonight!” This reaches its likely peak, in a speech given by the hobo in a hospital to a room of newborn infants. While “tears in rain” may be his most famous monologue, this is surely little less worthy of renown

A long time ago I was one of you. You’re all brand new and perfect. No mistakes, no regrets. People look at you and think of how wonderful your future will be. They want you to be something special… like a… a doctor or a lawyer. I hate to tell you this, but if you grow up here, you’re more likely to wind up selling your bodies on the streets, or shooting dope from dirty needles in a bus stop. And if you’re successful, you’ll make money selling junk to crackheads. And you won’t think twice about killing someone’s wife, because you won’t even know what was wrong in the first place. Or, maybe… you’ll end up like me… A hobo with a shotgun!

The level of awesome which this film frequently reaches cannot be over-stated. Of course, you can certainly look at this and see nothing more than a cheap, juvenile B-movie which thinks a shotgun duct-taped to point at someone’s dick is funny. But sue me: because it is funny, I’d say. While it may require a certain mindset to appreciate this, if you have that mindset, it’s damn near perfect cinema.

Original review [July 2011] A delightful throwback to the 80’s style hyperviolent exploitation flick see Hauer play the titular vagabond, who hops off a train in Hope Town, only to find it fails completely to live up its name. It has become a crime-ridden cesspool, overseen by The Drake (Downey) and his sons Ivan and Slick. After rescuing hooker Abby (Dunsworth) from Slick’s attentions, he is badly-beaten by the cops to who he delivers Slick, though Abby rescues him and tends to his wounds. When the Hobo stops a robbery at a pawn-store, it’s the turning point, and he becomes a vigilante, dishing out double-barrelled justice to The Drake’s men, and the others who have turned Hope Town into the festering sore that it has become. Needless to say, the crime boss is none too happy at the cowed residents having a figure other than him to whom they can turn. His sons fail to deal with the Hobo, so The Drake calls in The Plague, a pair of heavily-armoured killers, to deal with the threat, once and for all.

This is a gory, relentlessly offensive and enormously fun blast: in how many other films would the makers dare have the bad guys incinerate a bus full of schoolkids? But it centers on a typically-great performance from Hauer, who takes a character that could easily have been nothing more than a tattier version of Charles Bronson, and gives him and actual heart, even as the madness oscillates all around him. Credit also due to Downey, who delivers a startling turn that’s a complete 180 from his best known role, milquetoast Stanley Tweedle in Lexx. It has a consistent tone, something often forgotten by those who want to be “grindhouse”, slipping in little smirks to their intended audience, to prove they don’t mean it. Eisener is deadly serious, and the film is all the better for it. If the production values are occasionally flaky, the intent is clear from the moment the Hobo arrives on a rail, as the theme for Cannibal Holocaust plays. If you’re thinking, “That’s awesome!” – and you should be – I need say little more. B+