Back before there was Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing, the first star of British horror cinema was Tod Slaughter. While South London’s William Henry Pratt had to move to Hollywood in order to become a star, Slaughter’s fame was entirely due to his activities in the United Kingdom. He never seems to have given serious thought to moving to the United States, in part because his roots – and to a large degree, his stardom – were a result of the particularly British theatrical phenomenon known as melodrama. That brought him more than enough fame, over a period of decades, that moving to America likely would have brought no particular benefit.

Of course, the name with which this early horror movie villain was born wasn’t Tod Slaughter. It was Norman Slaughter. Though in his early career, he used his middle name, being billed as N. Carter Slaughter, and the roles he took on were normal ones. Indeed, he sometimes played the hero or supporting characters in productions of plays where he would later portray the bad guy on screen, such as The Face At the Window or Maria Marten. He took over the Elephant and Castle Theatre in London in 1924, and along with the Collins’s Music-hall in Islington, was instrumental in reviving the glories of the Victorian melodrama.

To quote an article in The Spectator from April 1926, “Here are no haunting psychological problems, such as Mr. James Joyce confronts us with in Exiles, no lights and shades of vice and virtue; the villain does not show one trace of humanity or decent feeling until, at the end of the last act, he reforms or dies repentant; the heroine, unless ‘betrayed,’ never wanders from the paths of purity, and the hero’s morals are as stainless as his entrances are opportune.” It more or less comes from the same stock as that other British staple, pantomime. Albeit with more drama, and (somewhat) less comic relief.

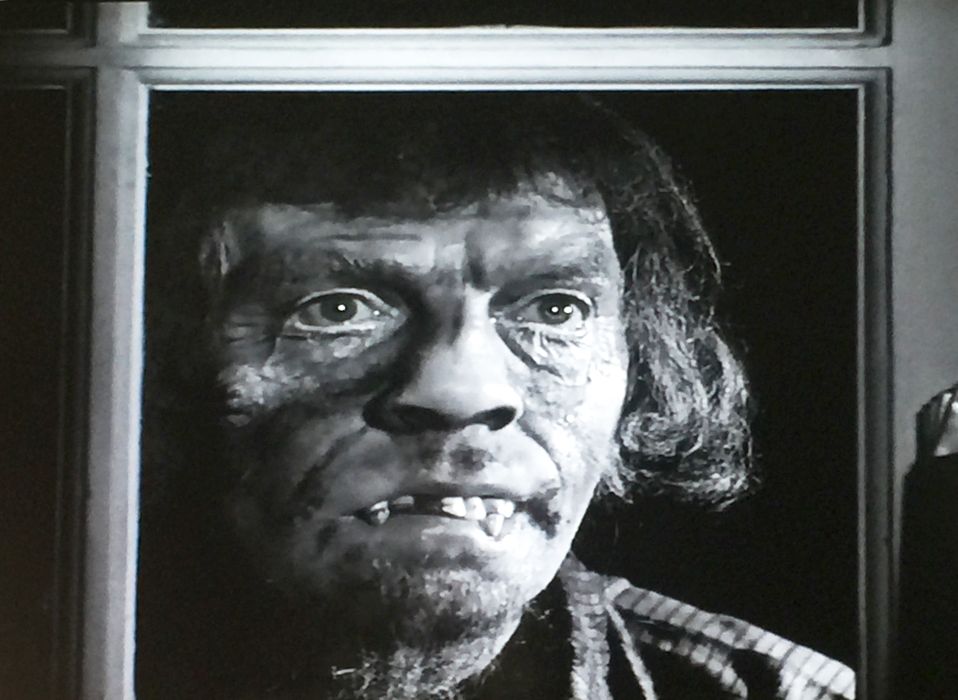

By the early thirties, Slaughter had adopted his most famous name, and was leaning into the villainous side. He was known as “Mr. Murder” for playing Long John Silver by day, and body snatcher William Hare by night, boasting that he killed fifteen people a day. Shortly after, he took up the role of Sweeney Todd, and his future career path was set. However, it wasn’t until he was nearly fifty that Slaughter first appeared on the movie screen. Many of his most memorable roles were adaptations of the same melodramas he had produced in the theatre. While this led to him largely being typecast, Tod a) didn’t appear to mind, and b) was damn good at his mustache-twirling evildoing.

To be honest, most of his work is low-budget, and it occasionally shows. Many were made as “quota quickies”. In 1928, a law came into effect requiring British cinemas to show a certain percentage of movies produced in Britain and the Commonwealth, and this did create a market for cheap features to count against the requirement. As such, most of Slaughter’s work didn’t travel well, getting only relatively minor distribution in America. His career continued into the fifties (the pic above is from a 1954 production of Sweeney Todd), and his play based on Spring-Heeled Jack became one of the first live productions put on by the BBC, broadcast from the Theatre Royal in Stratford. Slaughter died in 1956 – appropriately, after a performance of Maria Marten – and was largely forgotten over the decades since.

But there has recently been a renewal of interest, with a box-set of his work, The Criminal Acts of Tod Slaughter, released in 2023. Let’s take a look at five of his most famous performances. You bring the cheese and bread, for Mr. Slaughter will provide all the ham we can eat…

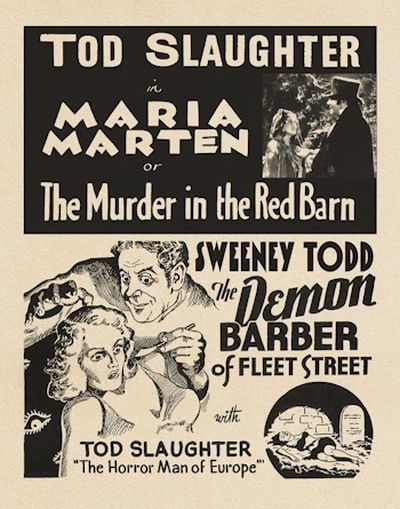

Maria Marten, or the Murder in the Red Barn (1935)

Rating: C+

Dir: Milton Rosmer

Star: Tod Slaughter, Sophie Stewart, Eric Portman, D.J. Williams

The inspiration for this was a notorious real-life murder from 1827, where Maria Marten was shot dead by lover William Corder at the titular location. He was eventually caught, confessed and hung for the crime, his body being given to science. The case caused enormous popular interest. The story was first adapted as a play before Corder was even executed, the barn was reportedly turned into souvenir toothpicks, while Corder’s skin was tanned and used to bind an account of the murder. Which seems deliciously harsh. This stage version makes Corder into a older man – in reality, he was a couple of years younger than the victim – and Marten an innocent, rather than the unmarried mother she actually was.

It’s the fifth film adaptation, after silent ones in 1902, 1908, 1913 and 1928, though only the last has survived. The origins as a play are hardly concealed here: it begins with a “reverse curtain call”, introducing the various cast members and their characters. Slaughter was familiar with the part, in addition to on stage, he played it in a BBC radio play, broadcast in November 1934. However, there’s no denying the relish he brings to the villainous role of Squire William Corder, as he seduces Maria (Stewart) away from her true love, Carlos (Portman), part of the local Gypsy community, only to discard her. When Maria discovers she’s pregnant, her father (Williams) blames Carlos and kicks her out. Corder, meanwhile, has already moved onto his next target, a rich spinster. Fearing Maria’s interference, he lures her to the barn. Of course, no villain in a Victorian melodrama ever gets away with their crimes.

It’s clear from the start that Squire Corder is a slimy and morally bankrupt character. Yet there’s still charisma, apparent in the opening scene at the village dance. It certainly works on Maria, who goes from zero to loss of virtue (implied, anyway) with remarkable speed – say, compared to Tess of the Durbevilles. But she is still a generally sympathetic character, for similar reasons to Tess, being guilty of not much more than naivety. While Carlos can be a bit stalkery at times, this is an unusually sympathetic portrayal of a Romany for this era. He never wavers, despite being the prime suspect in Maria’s disappearance, largely due to prejudice and circumstantial evidence, and gets the last laugh, becoming Corder’s executioner.

It’s clear from the start that Squire Corder is a slimy and morally bankrupt character. Yet there’s still charisma, apparent in the opening scene at the village dance. It certainly works on Maria, who goes from zero to loss of virtue (implied, anyway) with remarkable speed – say, compared to Tess of the Durbevilles. But she is still a generally sympathetic character, for similar reasons to Tess, being guilty of not much more than naivety. While Carlos can be a bit stalkery at times, this is an unusually sympathetic portrayal of a Romany for this era. He never wavers, despite being the prime suspect in Maria’s disappearance, largely due to prejudice and circumstantial evidence, and gets the last laugh, becoming Corder’s executioner.

Slaughter turned fifty the year his screen debut was released, and in his performance, you can tell he has more experience in the theatre. It’s a very “stagey” approach, and particularly in close-up, could be seen as chronic overacting. However, given the material, I would be hard-pushed to call it inappropriate here. The actor goes increasingly over the top after Corder’s own dog discovers Maria’s grave, and the landowner is made to dig it up. This uncovers first his pistol – conveniently, one of a matching pair, the other recently handed to a bystander – then the corpse of his victim. By the time his hopes of a stay of execution are snatched away, near-hysteria is probably understandable. Subtlety? It’s clearly vastly overrated.

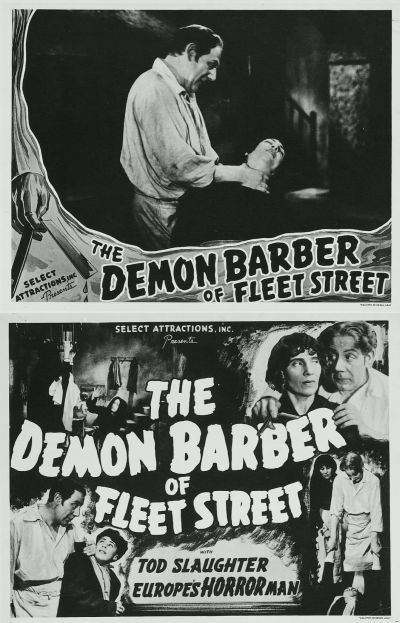

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1936)

Rating: C+

Dir: George King

Star: Tod Slaughter, Stella Rho, Eve Lister, Bruce Seton

This was the third movie adaptation of the story in a decade. There was a brief (fifteen minute) version in 1926, followed two years later by one which was at least feature length, though still silent. The role of Sweeney Todd was one with which Slaughter was already familiar. He had played it in the theatre: an audio recording of excerpts was released by Regal Zonophone Records in 1932. He was thus the obvious choice to star in a film version, especially one directed by King, the producer of Maria Marten. This movie cemented it as his signature role, and Slaughter would continue to depict the character on stage for the remainder of his life, until his death in 1956.

The story likely needs little repeating. Barber Sweeney Todd (Slaughter) makes money dumping customers into his cellar and slitting their throats. He has a partnership with Mrs. Lovitt (Rho, also the gypsy fortune teller in Maria Marten), who runs the pie-shop next door, to use the corpses in her product. Although in this version, the connection is only implied, and left up to the audience, presumably to avoid problems with the censors. The closest the movie gets to stating it, is a comedic moment where someone wonders how Todd disposed of the corpses, while chowing down on one of Mrs. Lovitt’s delicacies. [Ninety years earlier, the original penny dreadful story which introduced the world to the saga of Todd, The String of Pearls, was able explicitly to state, “The pies are made of human flesh!”]

Running alongside is the romance between sailor Mark Ingerstreet (Seton) and merchant’s daughter Johanna Oakley (Lister). Her father disapproves of this, instead welcoming Todd’s creepy attentions. Considering Slaughter was more than twice Lister’s age, the modern audience will be firmly on her side. Naturally, Mark returns from gaining his fortune in Africa, just in time to save her. Although he survives his time in the barber’s chair, it is only with the help of Mrs. Lovitt. She is motivated either by jealousy of Johanna, or greed – it’s not completely clear. But the relationship between them has felt a little fraught from the beginning: she suspects he is not being straight with her, in terms of divvying up their ill-gotten gains.

Running alongside is the romance between sailor Mark Ingerstreet (Seton) and merchant’s daughter Johanna Oakley (Lister). Her father disapproves of this, instead welcoming Todd’s creepy attentions. Considering Slaughter was more than twice Lister’s age, the modern audience will be firmly on her side. Naturally, Mark returns from gaining his fortune in Africa, just in time to save her. Although he survives his time in the barber’s chair, it is only with the help of Mrs. Lovitt. She is motivated either by jealousy of Johanna, or greed – it’s not completely clear. But the relationship between them has felt a little fraught from the beginning: she suspects he is not being straight with her, in terms of divvying up their ill-gotten gains.

Slaughter commands attention throughout, and is incredibly creepy from the first time we see him, lounging against a wall down by the docks. He gets good help from Rho, and I must also mention John Singer, playing Sweeney’s little apprentice Toby – the eighth such boy, in less than a couple of months. The terror on his face, as Todd beckons him with both index fingers and asks, “Are you afraid of me, Tobias?” (top) seems completely genuine. Inevitably, the romantic angle works less well, and there’s a lengthy diversion to Mark’s adventures in Africa, which is thoroughly unnecessary, bringing the film to a grinding halt. It remains better than the Tim Burton/Johnny Depp version, I’d say: the absence of Sondheim here is a clear mark in its favour.

The Crimes of Stephen Hawke (1936)

Rating: B-

Dir: George King

Star: Tod Slaughter, Marjorie Taylor, Eric Portman, Graham Soutten

This certainly begins in an unusual way, with eight minutes of effectively a BBC radio variety show broadcast. There’s a comic song from due Flotsam and Jetsam (a predecessor to Flanders and Swann), an interview with a cats’ meat man about his trade, and then – finally relevant – Slaughter appears to promote the film we are watching (which seems curiously pointless, since we are, in fact, already watching it). Asked if he has a favourite method of murder, he says, “I keep a perfectly open mind on the matter. I murder by strangulation, poisoning, shooting, stabbing or with a razor.” He mentions his roles both in Maria Marten and Sweeney Todd, by way of an introduction to the “old new melodrama” which then unfolds.

This does vary from other entries in a couple of ways. Firstly, it isn’t an adaptation of a previous story, but an entirely new tale. Secondly- and definitely a plus – there’s no inappropriately young love interest for Slaughter. Instead, he’s the titular money lender, who moonlight at a serial killer, baptised by the press with the glorious name of “The Spine-breaker”, in reference to his preferred way of dispatching victims. It’s never quite clear why he does this: robbery seems a partial motive in some cases, but the first we see him, he murders a young boy. Nobody initially suspects Hawke, who has an adopted daughter, Julia (Taylor). She is in love with Matthew (Portman), the son of Hawke’s business partner, Joshua Trimble.

Joshua eventually discovers Stephen’s alter ego, after seeing him snap a statue with his abnormally strong hands, and, inevitably, is quickly dispatched. However, he left a document incriminating Hawke, and when Matthew finds out the truth, he gives the killer a chance to run before beginning pursuit: “You shall be like a hunted animal. But as a fox is given a chance to run for his life, so should you be allowed to flee. For Julia’s sake, I hope you’ll elude me.” Julia is rather ambivalent about this, and with her guardian no longer around, is co-opted into an unwanted, blackmail-fuelled engagement. This, intriguingly, ends up putting the fugitive Stephen and the hunter Matthew on the same side, both intent in stopping Julia’s marriage.

Joshua eventually discovers Stephen’s alter ego, after seeing him snap a statue with his abnormally strong hands, and, inevitably, is quickly dispatched. However, he left a document incriminating Hawke, and when Matthew finds out the truth, he gives the killer a chance to run before beginning pursuit: “You shall be like a hunted animal. But as a fox is given a chance to run for his life, so should you be allowed to flee. For Julia’s sake, I hope you’ll elude me.” Julia is rather ambivalent about this, and with her guardian no longer around, is co-opted into an unwanted, blackmail-fuelled engagement. This, intriguingly, ends up putting the fugitive Stephen and the hunter Matthew on the same side, both intent in stopping Julia’s marriage.

The dialogue here is particularly sharp, such as Hawke telling his next victim, “Perhaps you’d allow me to call on you one night alone. Then we could get to grips with the matter.” When the unsuspecting man asks, “You will back me up?”, he is told, “Definitely. You’ll find me behind you…” This might be a result of the script being directly written for the screen, rather than being an adaptation of a stage play. It’s also notable that Hawke is not the psychopath we have seen Slaughter play previously: he genuinely cares for Julia, which makes his predilection for back-breaking work all the more inexplicable. But it’s no less entertaining for this – and educational too, with regard to now long-lost, feline-related professions.

The Face at the Window (1939)

Rating: B-

Dir: George King

Star: Tod Slaughter, John Warwick, Marjorie Taylor, Aubrey Mallalieu

This melodramatic thriller gallops along, cramming a lot into its running-time, of barely more than an hour. It takes place in Paris, in the year 1880, when a killer is terrorising the city. Wolf-like howls precede the murders, generating wild rumours as to their provenance. The latest victim is the night watchman at a bank owned by Monsieur de Brisson (Mallalieu). The gold taken has sent the financial repository to the edge of insolvency. Fortunately, a lifeline appears in the shape of the aristocratic Chevalier del Gardo (Slaughter). His deposit will secure the bank’s reputation and stabilize its operations. All the Chevalier wants in exchange is the hand of de Brisson’s daughter, Cecile (Taylor).

In line with what feels increasingly like standard Slaughter protocol, the heroine is almost half his age, and already has a fiancé. He’s the poor but honest bank clerk, Lucien Cortier (Warwick), and so she spurns del Gardo’s advances. Undaunted, he decides to clear the playing-field by framing Cortier for the murder-robbery, hiding some pieces of gold in the clerk’s desk. Cortier begs his employer for a chance to clear his name before the police are called. But that will involve finding the real culprit behind the crime. No prizes for guessing who it might be, though it ends up being both more and less complicated than I expected. It nods somewhat to the tropes of werewolf movies, though the play on which it was based dates back to 1897, and the lupine angle never proves crucial.

What does prove critical, is the mad science of Cortier’s scientist friend, using galvinism to energize corpses. Which comes in particularly handy, after one victim dies right in the middle of writing the killer’s identity. Maybe if he had just gone with that, not bothering to prefix it with, “The name of the Wolf is…”, he might have got further than three characters in, before ceasing to be. Just a thought. There are certainly other elements here which likely would not stand up to close scrutiny. The good news is, you won’t have time to dwell on them, because the script is already tapping its watch and charging on to the next element. Perhaps the original Victorian play ran longer, and could take a more leisurely approach?

What does prove critical, is the mad science of Cortier’s scientist friend, using galvinism to energize corpses. Which comes in particularly handy, after one victim dies right in the middle of writing the killer’s identity. Maybe if he had just gone with that, not bothering to prefix it with, “The name of the Wolf is…”, he might have got further than three characters in, before ceasing to be. Just a thought. There are certainly other elements here which likely would not stand up to close scrutiny. The good news is, you won’t have time to dwell on them, because the script is already tapping its watch and charging on to the next element. Perhaps the original Victorian play ran longer, and could take a more leisurely approach?

It had been filmed three times previously, though nobody particularly remembers the other versions. There’s an opening caption here, which should set your expectations adequately. It promises a “melodrama of the old school – dear to the hearts of all who enjoy either a shudder or a laugh at the heights of villainy”. It’s hard to argue the film delivers exactly that, with Slaughter at the core of proceedings, delivering both the shudders and laughs – occasionally at the same time. Few other actors can deliver a simple line like, “Oh, I shall be there. Punctually,” and instill it with menace befitting a Hannibal Lecter monologue. Truly the heights of villainy, indeed.

Crimes at the Dark House (1940)

Rating: B

Dir: George King

Star: Tod Slaughter, Sylvia Marriott, Hilary Eaves, Hay Petrie

Despite the title, this is actually an adaptation of one of my favorite book, classic Gothic novel The Woman in White, by Wilkie Collins. This has been adapted frequently into other media. We previously reviewed the 1948 film version. The retitling initially seemed weird, like an attempt to hide the source. Yet it wasn’t long before it made perfect sense, since it’s a radical enough reworking to merit its own name. In the book, evil aristocrat Sir Percival Glyde’s dark secret is he’s illegitimate, and so not entitled to the estate he has claimed. Here, he’s an impostor (Slaughter). He murdered the emigrant lord, who had been in Australia for decades, after learning of an inheritance, returning to England in his place.

Unfortunately, the inheritance is mostly debts. But a possible out is a previously arranged marriage to rich heiress Laurie Fairlie (Marriott). However, doing so will require “Sir Percival” – take the quotes as read hereafter – to deal with everyone who can expose his fraud, through bribery or murder, as well as the clingy servant girl he has been banging (top). The film does retain the novel’s titular lunatic, flitting around the grounds in her Gothic nightie. She is a lookalike for Laurie, a fact Sir Percival uses to his advantage. But in place of the book’s multiple viewpoints, this is largely told from the antagonist’s perspective. It’s also significantly stripped-down, out of necessity, to fit into the 69-minute running-time.

There is no real secret here either. Right from the start, we are entirely aware Sir Percival is an impostor. This is because we see him murdering the real one, by hammering a tent peg into the sleeping lord’s ear. The tension instead comes from whether this will be discovered, by anyone he can’t bribe – which excludes highly buyable local physician, Dr. Fosco (Petrie) – or bump off in the nearby boathouse. Slaughter is incredibly fun to watch, ramping up the melodramatic villainy to eleven, snarling lines like “I’ll feed your entrails to the pigs!” to his accomplice. He occasionally reaches twelve, such as on the night of his wedding to Laurie. Rarely has a fade to black been more laden with sordid overtones.

There is no real secret here either. Right from the start, we are entirely aware Sir Percival is an impostor. This is because we see him murdering the real one, by hammering a tent peg into the sleeping lord’s ear. The tension instead comes from whether this will be discovered, by anyone he can’t bribe – which excludes highly buyable local physician, Dr. Fosco (Petrie) – or bump off in the nearby boathouse. Slaughter is incredibly fun to watch, ramping up the melodramatic villainy to eleven, snarling lines like “I’ll feed your entrails to the pigs!” to his accomplice. He occasionally reaches twelve, such as on the night of his wedding to Laurie. Rarely has a fade to black been more laden with sordid overtones.

The rest of the cast are more of a mixed-bag. To be fair to Marriott, the script does follow the book in making Laurie much less interesting than her sister, Marian (Eaves). The latter is definitely the smarter one, though here, largely acts as her sibling’s moral spine. This is most obvious in the scene where Sir Percival is trying to get his bride to sign over her fortune to him. Only the fortuitous arrival of Marian prevents this disaster from becoming legally binding. But if there is a moral here, it is that it’s probably best not to confess a litany of crimes, up to and including murder, unless you have first carefully swept the area for accidentally eavesdropping relatives. Otherwise, a fiery doom is inevitable.