Rating: C

Dir: Jhonny Hendrix

Star: Luis Felipe Cortés, Robín Abonía, Estefanía Borge, Juan Ángel

a.k.a. Saudó, Labyrinth of Souls

My experience of Colombian culture has been less on the cinematic side, and more watching narconovelas such as Miss Adrenaline. I suspect these provide a… shall we say, over-dramatic representation of life there, in the same way American soaps do not accurately portray everyday experiences in hospitals or whatever. While they’re not exactly out of business, I – perhaps optimistically – hope that drug cartels do not present the omnipresent threat depicted in the likes of Rosario Tijeras. Things do seem to have calmed down, compared to the days when Medellin was the murder capital of the world: the homicide rate there declined by ninety-seven percent since the death of Pablo Escobar.

Before this project, I think I had only seen one horror movie made in that country, 2011’s Blind Alley. Outside of Brazil, it feels as if South American in general has rarely embraced the genre. I read a suggestion, quoting Buñuel, that this was because Latin American culture has no haunted castles or stories of zombies or vampires, which could fuel such movies. That may be a factor, yet there is no shortage of local folklore and legends, some of them undeniably horrific in nature, that might be used as inspiration by film-makers. Colombia, for example, has La Tunda, a shapeshifter who will adopt the form of a loved one to lure its prey into the forest, and consume them.

That is, however, weak horror sauce compared to the Boraro. Although I’m not convinced this isn’t someone having a laugh, per Wikipedia: “It is tree sized, pale skinned but covered in black fur, has large forward facing ears, fangs and huge pendulous genitals. It has no joints in its knees, so if it falls down it has great trouble getting up. It uses two main ways to kills its victims, first its urine is a lethal poison. Secondly, if it catches a victim in its embrace it will crush them without breaking skin or bones, until their flesh is pulp. Then it drinks the pulp through a small hole made in the victims head, after which the victims empty skin is inflated like a balloon and are then sent home in a daze, where they subsequently die. It can be placated by tobacco.”

That is, however, weak horror sauce compared to the Boraro. Although I’m not convinced this isn’t someone having a laugh, per Wikipedia: “It is tree sized, pale skinned but covered in black fur, has large forward facing ears, fangs and huge pendulous genitals. It has no joints in its knees, so if it falls down it has great trouble getting up. It uses two main ways to kills its victims, first its urine is a lethal poison. Secondly, if it catches a victim in its embrace it will crush them without breaking skin or bones, until their flesh is pulp. Then it drinks the pulp through a small hole made in the victims head, after which the victims empty skin is inflated like a balloon and are then sent home in a daze, where they subsequently die. It can be placated by tobacco.”

While we wait for Guillermo del Toro to get on with that, we have this film. It is also inspired by a folk tale, albeit not of the “entirely off your face on ayahuasca” kind. The director said. “It was born from research in Chocó, in which people involved with Santeria and witchcraft were interviewed. We found a woman who was supposedly the most important in this field and we went to her house with a bale of tobacco and four bottles of rum. After drinking three of these as if they were water, she told the story of a town deep im the Pacific jungle, to which escaped slaves had fled. They performed a ritual to make themselves invisible to the outside world, so they would not be captured again.”

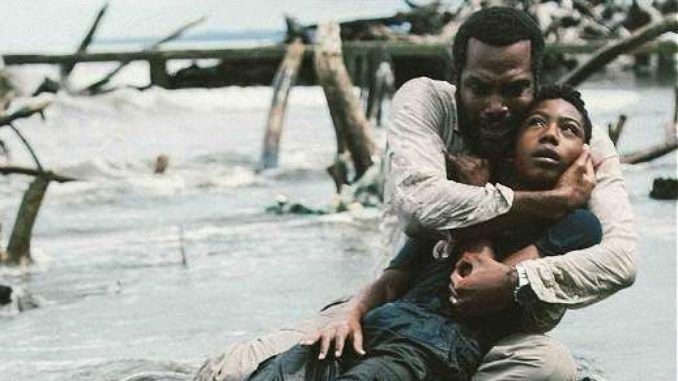

That tale became the basis for the film, as an opening caption explains: “That place was called Saudo, where only fertile women were allowed to stay. The men would fight to the death until only one would be left standing; the king, the Mandingo, for he would engender a whole people.” The hero is Elias (Cortés), who escaped the village at the age of thirteen, thereby avoiding such a fate. He moved to the big city, eventually becoming a doctor, as well as getting married to Sofia (Borge), with whom he has had a son, Francisco (Abonia). However, Francisco is now thirteen too, and both father and son are experiencing nightmares, which Elias feels can only be cured by their return to his hometown.

Needless to say, that trip ends up going about as well as you’d expect, and it’s a decision which has to rank as dumb, even by the low standards of horror movie characters. Admittedly, there is a ‘Get out of Jail Free’ card, in the shape of occult influence, which can be used to hand-wave away almost any plot necessity. #BecauseWitchcraft gets a lot of mileage here. Though Hendrix does a good job of generating a sense of foreboding and dread, as Elias tries to go about his everyday life, despite the increasing concerns of Sofia as to his behaviour. Little things work quite well, such as the struggle Elias has finding anyone in the region who’ll even acknowledge the existence of Saudó.

The problems mount on the arrival in his home-town, where things get considerably stranger after they are reunited with Elias’s mother. She is remarkably – indeed, suspiciously – calm at the return of her son after twenty-plus years. I watched this section of the film twice, and I’m still not prepared to offer an opinion on how the movie chooses to resolve things. It seems often to be a problem with films in this sub-genre of horror, that the makers have difficulty sticking the landing satisfactorily. Things just about hang on, mostly because you feel invested in Elias, thanks to Cortés’s strong performance. But it feels the script shirks its responsibilities, leaving the viewer to do too much in the final lap.

The problems mount on the arrival in his home-town, where things get considerably stranger after they are reunited with Elias’s mother. She is remarkably – indeed, suspiciously – calm at the return of her son after twenty-plus years. I watched this section of the film twice, and I’m still not prepared to offer an opinion on how the movie chooses to resolve things. It seems often to be a problem with films in this sub-genre of horror, that the makers have difficulty sticking the landing satisfactorily. Things just about hang on, mostly because you feel invested in Elias, thanks to Cortés’s strong performance. But it feels the script shirks its responsibilities, leaving the viewer to do too much in the final lap.

Saudó ended up beating out another couple of candidates, mostly through being the most overtly horror-centric. Pueblo De Cenizas fell more into the ‘magical realism’ category. While it had a few elements of horror – witchcraft again played a significant part – they felt very much secondary to what was more a family drama, set on a coffee plantation in the fifties, and was pretty dull. There was also Luz: The Flower of Evil. While it might end up getting a review down the road (and is very nicely photographed), it’s closer to a psychological study in religious fanaticism. Despite its flaws, Saudó feels a better representation of the state of the genre. Now, about that Boraro movie…

This review is part of our October 2024 feature, 31 More Countries of Horror.