Rating: C

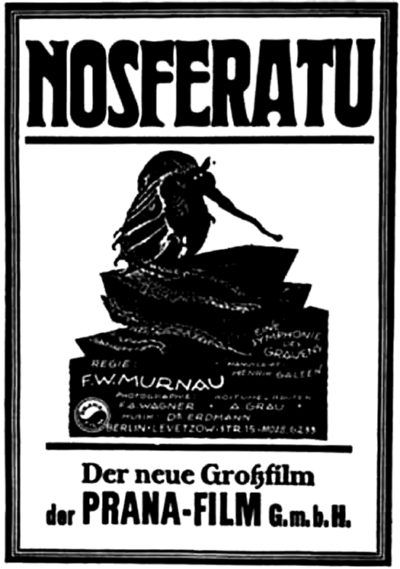

Dir: F. W. Murnau

Star: Max Schreck, Gustav von Wangenheim, Greta Schröder, Alexander Granach

Full disclosure. I have a problem with silent movies. In fact, it’s an impressive feat if one of them avoids sending me into slumberland. It’s not as if the makers chose to be silent, as some kind of artistic decision. Sound simply wasn’t an option, and due to this, the results typically feel as if they were making a film with one arm tied behind their back. When you can’t have dialogue – or at least are severely limited, to what you can cram into occasional intertitles – story-telling becomes much more difficult. Not so much the broad strokes: after all, this is an unauthorized adaptation of Dracula, so the story’s pretty obvious. It’s the subtleties that are usually lost, and mostly replaced by exaggerated over-acting for emphasis.

I can still respect these early efforts, which often contain striking visual imagery, as good as anything you’ll find nowadays. That’s just not enough for me. I’m a big fan of a well-developed plot, and that’s something almost impossible to do in a silent film. I understand these film-makers laid the foundation for what was to come, and certainly do not deny them their place in the history of the art. However, the same could be said about the cave paintings of Lascaux, and I would not want them hanging on the walls here at FilmBlitz Towers. Silent films are, to me, like having to eat gourmet food while holding your nose. The overall experience is inevitably going to be diminished as a result of the limitations, even if those were not, in any way, a fault of the creators. And it’s the experience I care about.

That all said, on to Nosferatu specifically. It may not be the first feature-length horror film, but it is likely the first influential feature-length horror. Put it this way, I don’t see anyone remaking 1911’s Dante’s Inferno any time soon, in the way Robert Eggers just finished shooting a remake of Nosferatu. It’s especially impressive because, as is well-known, this almost became one of the many lost films from the early days of cinema. Bram Stoker’s widow Florence sued the makers, and the resulting settlement in the German courts demanded the destruction of all prints. Fortunately, a print or two escaped to America, where the decision had no sway. Its reputation then began to grow, and when Dracula entered the public domain, Nosferatu rose from the copyright grave.

That all said, on to Nosferatu specifically. It may not be the first feature-length horror film, but it is likely the first influential feature-length horror. Put it this way, I don’t see anyone remaking 1911’s Dante’s Inferno any time soon, in the way Robert Eggers just finished shooting a remake of Nosferatu. It’s especially impressive because, as is well-known, this almost became one of the many lost films from the early days of cinema. Bram Stoker’s widow Florence sued the makers, and the resulting settlement in the German courts demanded the destruction of all prints. Fortunately, a print or two escaped to America, where the decision had no sway. Its reputation then began to grow, and when Dracula entered the public domain, Nosferatu rose from the copyright grave.

I can’t say I blame Florence for filing suit. While the name of every character have been changed, the bulk of the story-line is a direct and undeniable lift. Real-estate agent Thomas Hutter (von Wangenheim) travels to Transylvania to complete the purchase of an estate by nobleman, Count Orlock (Schreck), who is, of course, a vampire. Orlok relocates to Hutter’s hometown of Wisborg on a boat, which arrives with the whole crew dead, and begins his predations. It’s here where the plot diverges, with Orlock’s attacks being seen as symptomatic of a plague, until Hutter’s wife Ellen (Schröder) decides to sacrifice herself. She lures Orlock into staying with her past dawn, and the sunlight destroys him. This became a core element of vampire lore, but in Stoker’s novel, it only weakened them.

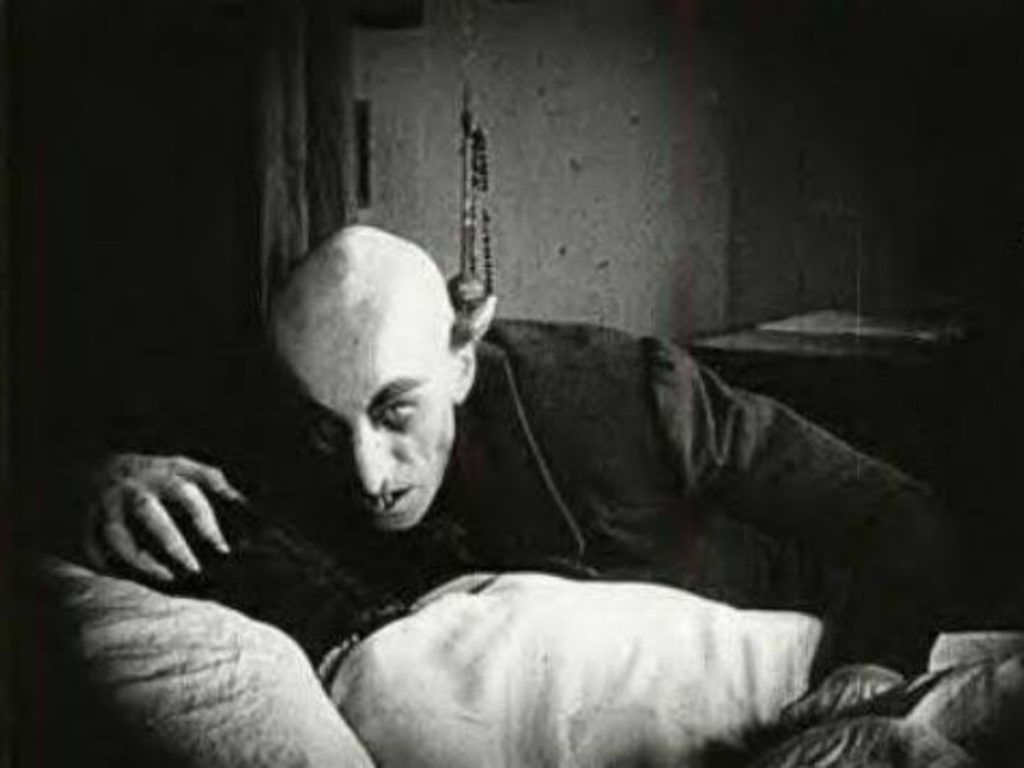

The main change, however, is the look of the vampire. Far from the urbane aristocrat in the portrayals of Bela Lugosi or Christopher Lee, Count Orlock is a freakish, ugly creation, all angles and whose idea of conversation is, I quote, “Your wife has a nice neck.” This also differs from Werner Herzog’s remake of Nosferatu, where Klaus Kinski played the vampire with “the tortured angst of an immortal soul, who yearns for death as an escape from his loveless existence.” There’s no notion that Orlock can turn people into vampires either. They just die when he has finished sucking their blood. It’s no surprise some have read this version as anti-Semitic, with Orlock’s features cruelly stereotypical, and his character a version of the Wandering Jew, doomed to wander Earth as an immortal. Given the fondness in the Middle Ages for blaming Jews as spreaders of plague, and the ways things were trending in Germany, it doesn’t seem a stretch – albeit perhaps not a subtext Murnau intended.

I found it least effective when it was simply being a straight knock-off of Dracula, though it was somewhat interesting to see “Jonathan Harker” in his happy home-life before leaving for Transylvania. The first half is familiar, and once you get over the shock at Orlock’s striking appearance, offers little we haven’t seen done elsewhere, and considerably better. Once Orlock arrives in Wisborg, the film begins to acquire its own identity, with elements such as the disease-bearing nature of the curse, and is the better for it. It’s no surprise that most of the scenes which have become part of our common cultural consciousness, such as the shadow on the stairs (top), come from later in proceedings. I definitely can’t argue the iconic nature of that shot, and can only imagine the impact it had on an audience in 1922.

I found it least effective when it was simply being a straight knock-off of Dracula, though it was somewhat interesting to see “Jonathan Harker” in his happy home-life before leaving for Transylvania. The first half is familiar, and once you get over the shock at Orlock’s striking appearance, offers little we haven’t seen done elsewhere, and considerably better. Once Orlock arrives in Wisborg, the film begins to acquire its own identity, with elements such as the disease-bearing nature of the curse, and is the better for it. It’s no surprise that most of the scenes which have become part of our common cultural consciousness, such as the shadow on the stairs (top), come from later in proceedings. I definitely can’t argue the iconic nature of that shot, and can only imagine the impact it had on an audience in 1922.

Outside of Orlock, however, there isn’t much to engage the interest in any of the performances. Indeed, I’d be hard pushed to separate the wild antics of Renfield-alike Knock (Granach) from the dramatic stylings of von Wangenheim or Schröder. The absence of a Van Helsing character, around whom the forces of good can rally, robs the middle act of much drama. It’s not until Ellen conveniently stumbles across a Manual of Exposition, that the story begins to move forward again. I did like that ending, although it renders Mr. Hutter basically irrelevant. His headlong rush back from Orlock’s castle turned out to be little more than a waste of time, the “little woman” proving capable of handling the threat without any assistance from her husband. As we’ll see over the rest of this series, it’s not common for women to be the vampire killers. In that way, at least, Nosferatu was well ahead of its time.

This review is part of our October 2023 feature, 31 Days of Vampires.