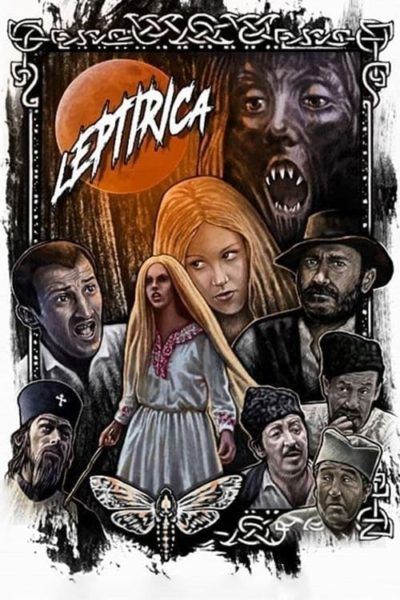

Rating: C

Dir: Djordje Kadijevic

Star: Petar Boźović, Mirjana Nikolić, Slobodan Perović, Vasja Stankovic

a.k.a. The She-Butterfly

This film, made for Yugoslavian television, has acquired a bit of a cult reputation as being an early work in the sub-genre of “folk horror.” It’s also regarded as the first home-grown Serbian horror movie, even though the location where it was shot is now in Bosnia-Herzegovina. It’s a fairly accurate adaptation, save for the ending, of After Ninety Years, a novella written by Serbian writer Milovan Glišić. What’s notable is that it was published in 1880, seventeen years before Bram Stoker’s Dracula came out. However, unlike Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, which similarly pre-dated Dracula and appears to have influenced some elements, After Ninety Years made few ripples outside its home country, not even seeing an English translation until 2015. As such, it’s very much a different style of vampire, with many elements that will likely differ from what you’re used to.

Events unfold in a 19th century rural village, which has a bit of a problem. The local watermill, which everyone uses to grind their grain, has gone through a series of millers. This is because they have an unfortunate tendency to turn up dead, their throats ripped out and drained of blood. The local farmers are now casting around for anyone dumb enough to take the position, and find an appropriate candidate in Strahinja (Boźović), a poor but honest young man, of the type typically found in fairy tales. He has lost his heart to the golden-haired Radojka (Nikolić), and they want to get married. However, her father is a rich land-owner, Živan (Perović), who pours cold-water on the idea, being thoroughly unimpressed by Strahinja’s lack of prospects and ability to support his daughter in the appropriate manner. The job at the mill might solve that problem.

However, his first night on the job is disturbed by an attack from the vampiric monster, which Strahinja survives, as much by luck as anything else. When he reports what happened to the farmers, they realize a vampire is responsible. The most likely candidate is a late inhabitant called Sava Savanović, so the posse of novice vampire hunters seek out the grave of Savanović (a stallion is involved in the process, which is definitely not something I’d heard before!), and attempt to drive a stake through the corpse’s heart. While they do, a butterfly escapes from the coffin, much to the hunters’ horror. For, in local folklore, the butterfly is kinda like their version of the bat in more “traditional” vampire literature, a form which the bloodsucker can adopt. So the danger may not have been disposed of as they hoped: it may simply have moved on to find another host.

However, his first night on the job is disturbed by an attack from the vampiric monster, which Strahinja survives, as much by luck as anything else. When he reports what happened to the farmers, they realize a vampire is responsible. The most likely candidate is a late inhabitant called Sava Savanović, so the posse of novice vampire hunters seek out the grave of Savanović (a stallion is involved in the process, which is definitely not something I’d heard before!), and attempt to drive a stake through the corpse’s heart. While they do, a butterfly escapes from the coffin, much to the hunters’ horror. For, in local folklore, the butterfly is kinda like their version of the bat in more “traditional” vampire literature, a form which the bloodsucker can adopt. So the danger may not have been disposed of as they hoped: it may simply have moved on to find another host.

It really doesn’t take Sherlock Holmes to figure out who that’s going to be. Let’s be honest, the translated title basically spoils any tension regarding the identity of the vampire. Though in the director’s defense, Kadijevic does not appear particularly concerned about that element. Indeed, for much of this, the horror elements seem to take second place – or possibly even further back – to gentle elements of rural comedy and a general depiction of pastoral life. Save for the scenes inside the mill, the entire film seems to take place in the fields and hills of deeply rural Yugoslavia: I swear, I have never heard so much birdsong in the background audio of a movie. The chirping is virtually non-stop. The comedy isn’t particularly funny, being things like the vampire hunters asking an old woman for directions to the grave of Sava Savanović, only for her to be quite hard of hearing. I’ll pause here, and let you hold your sides, since they must surely be splitting.

I would definitely have preferred Kadijevic to have focused on the horror elements, and there’s certainly room for expansion, since the whole things runs little more than an hour in length. I guess Yugoslavian TV was a big fan of brevity in its local productions. Nikolić is a stunning creature, Radojka skipping around the countryside with her flock, like an ancestor of Emmanuelle Beart in Manon des Sources. They could have stretched out proceedings between the butterfly escaping from Savanović’s grave, and Strahinja realizing that his new bride – for they do eventually elope and get wed, with the help of the farmers – has a mysterious stake-shaped wound in her chest. Though again, many of the usual tropes of vampirism are missing: Radojka being entirely untroubled by daylight, is one example. There’s also a whole transformation, which includes her skin turning black, and a nasty-looking mouthful of fangs.

This element does appear to differ significantly from the original story. There, the butterfly simply escapes, kills a few kids and leaves the region, while Strahinja and Radojka live happily ever after. This seems distinctly anticlimactic compared to the film, which goes on its own direction. Urban legend has it that someone in Yugoslavia died of fright during the initial screening. Part of me snorts derisively at the weak hearts of lily-livered Commies, although I do have to say, the film sticks the landing very well, especially for a seventies TV movie. The final shot (above), of a sleeping Strahinja, with a butterfly nestling ominously in his hair, is perhaps the best in the entire movie. After being far too low-key for the bulk of its duration, it does give the viewer something decent to take away with them.

This element does appear to differ significantly from the original story. There, the butterfly simply escapes, kills a few kids and leaves the region, while Strahinja and Radojka live happily ever after. This seems distinctly anticlimactic compared to the film, which goes on its own direction. Urban legend has it that someone in Yugoslavia died of fright during the initial screening. Part of me snorts derisively at the weak hearts of lily-livered Commies, although I do have to say, the film sticks the landing very well, especially for a seventies TV movie. The final shot (above), of a sleeping Strahinja, with a butterfly nestling ominously in his hair, is perhaps the best in the entire movie. After being far too low-key for the bulk of its duration, it does give the viewer something decent to take away with them.

While the technical elements are solid enough, and often pretty good, it just doesn’t commit to the darkness inherent in the material, leaning towards goofy comedy. For another instance, after his encounter with Savanović, Strahinja comes out of the mill covered in flour, to the horror of the farmers who mistake him for some ghoulish creature. It’s a joke which could have strayed in from a Benny Hill episode, and sits uneasily with the hero’s narrow escape from death. If Kadijevic can’t take his film seriously, why should anyone else?

This review is part of our October 2023 feature, 31 Days of Vampires.