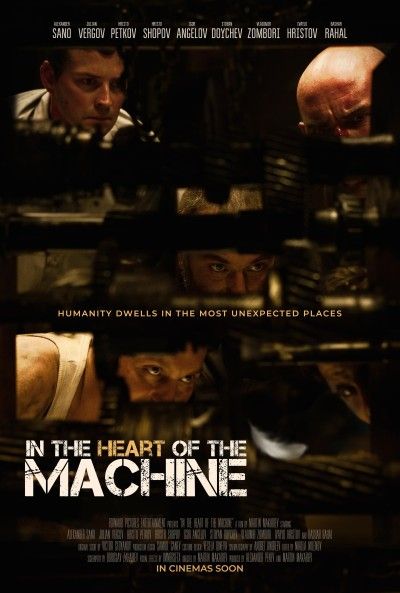

Rating: B+

Dir: Martin Makariev

Star: Alexander Sano, Julian Vergov, Igor Angelov, Hristo Shopov

Well, this was a surprise, on a number of levels. Not least that I initially thought it was Russian, a result of the Cyrillic lettering. But when the first line was, “Silence! Get in formation for the national anthem of the Republic of Bulgaria!”, it became clear we’re not in Moscow any more. It is, I believe, my first experience of Bulgarian cinema, and if this is any guide, it must be a treasure-trove of unexpected gems. However, a lot of local comments I read have been along the lines of “the best Bulgarian movie in the last 30 years,” I suspect Machine may be more the exception than the rule. Not that this dilutes its own merits in any way.

Perhaps think of it as a Bulgar version of The Green Mile. It takes place in 1978, well before the fall of Communism, when Bohemy (Sano) is trying to get through his lengthy sentence. The warden, Colonel Radoev (Shopov), offers Bohemy parole if he runs a work squad in a metal shop on day release. However, the job quickly goes pear-shaped as a hulking brute known, for good reason, as The Hatchet (Angelov), refuses to start his lathe because a pigeon is trapped inside. Things quickly escalate into a siege situation, with sadistic guard Captain Vekilsky (Vergov) one of the hostages. Bohemy sees his hard-won parole evaporating, while on the outside, Radoev is trying to stop colleagues from storming the workshop.

Knowing little about this, I was expecting a considerably less thoughtful, nuanced production. Remarkably, it’s based on a true story – the film is dedicated to the real Bohemy. Well, almost true: the bird was a sparrow, not a pigeon, and less violence was involved in the resolution. While it certainly does not skimp on that when necessary, it has a lot to say about what it means to be human. The trapped bird is clearly a metaphor for the prisoners (the title could apply to both), and that’s perhaps why The Hatchet feels so strongly about its release, at the risk of his own life. Not everyone agrees with him; among the group of prisoners, some would like to seize the unexpected chance to escape, while others want to surrender at the first opportunity, and Bohemy is just trying to get through the day. Some will not get what they want.

Knowing little about this, I was expecting a considerably less thoughtful, nuanced production. Remarkably, it’s based on a true story – the film is dedicated to the real Bohemy. Well, almost true: the bird was a sparrow, not a pigeon, and less violence was involved in the resolution. While it certainly does not skimp on that when necessary, it has a lot to say about what it means to be human. The trapped bird is clearly a metaphor for the prisoners (the title could apply to both), and that’s perhaps why The Hatchet feels so strongly about its release, at the risk of his own life. Not everyone agrees with him; among the group of prisoners, some would like to seize the unexpected chance to escape, while others want to surrender at the first opportunity, and Bohemy is just trying to get through the day. Some will not get what they want.

I loved the character work here in particular. No-one is portrayed as entirely evil; even Vekilsky has reasons for his behaviour, mostly rooted in an understandable fear of the prisoners. We gradually learn about the convicts’ backgrounds, as well as their aspirations – that a child-rapist can be made to seem almost likeable, says a lot about the excellent work put in by Makariev and his cast. By the end, you feel genuinely invested in the outcome for everyone, and it’s very much a bitter-sweet resolution. Albeit one which may leave you with a little bit more faith in humanity, than you had upon entry.