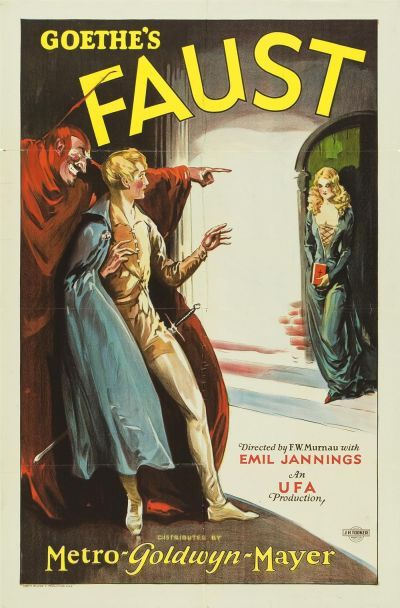

Rating: C-

Dir: F.W. Murnau

Star: Gösta Ekman, Emil Jannings, Camilla Horn, Frida Richard

There are a mere twelve horror movies on the IMDb, with over ten thousand ratings and a score better than eight. The second film in this feature, Diabolique, is one of those, and so it’s kinda appropriate that we finish off with another in that Golden Dozen, the earliest of the “uber-classic” horror movies. But I’m not going to deny: I wasn’t exactly looking forward to this one. My previous experiences with German Expressionism of the silent era, had tended to involve me providing my own soundtrack for the feature, reminiscent of wood being sawed. Yeah, these have been a challenge to my consciousness, in a very literal way. I actually postponed the viewing here, because it was originally scheduled for a day where I had got up at 3:30 am. That was just asking for trouble.

The legend of Faust was first recorded in the late 16th century, though its origins may be even earlier. It was supposedly inspired by Johann Georg Faust, an alchemist about whom not much is certain. His life and supposed pact with Satan was notably adapted by Christopher Marlowe in his Elizabethan tragedy, Doctor Faustus. This eventually made its way back to Germany, and was remade by Goethe into his own version of the story, Faust. It’s considered by some to be the greatest work in German literature, and has been influential on productions across many media since, from Franz Liszt’s Faust Symphony to Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise, which is as much Faustian as Phantom of the Opera.

The legend of Faust was first recorded in the late 16th century, though its origins may be even earlier. It was supposedly inspired by Johann Georg Faust, an alchemist about whom not much is certain. His life and supposed pact with Satan was notably adapted by Christopher Marlowe in his Elizabethan tragedy, Doctor Faustus. This eventually made its way back to Germany, and was remade by Goethe into his own version of the story, Faust. It’s considered by some to be the greatest work in German literature, and has been influential on productions across many media since, from Franz Liszt’s Faust Symphony to Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise, which is as much Faustian as Phantom of the Opera.

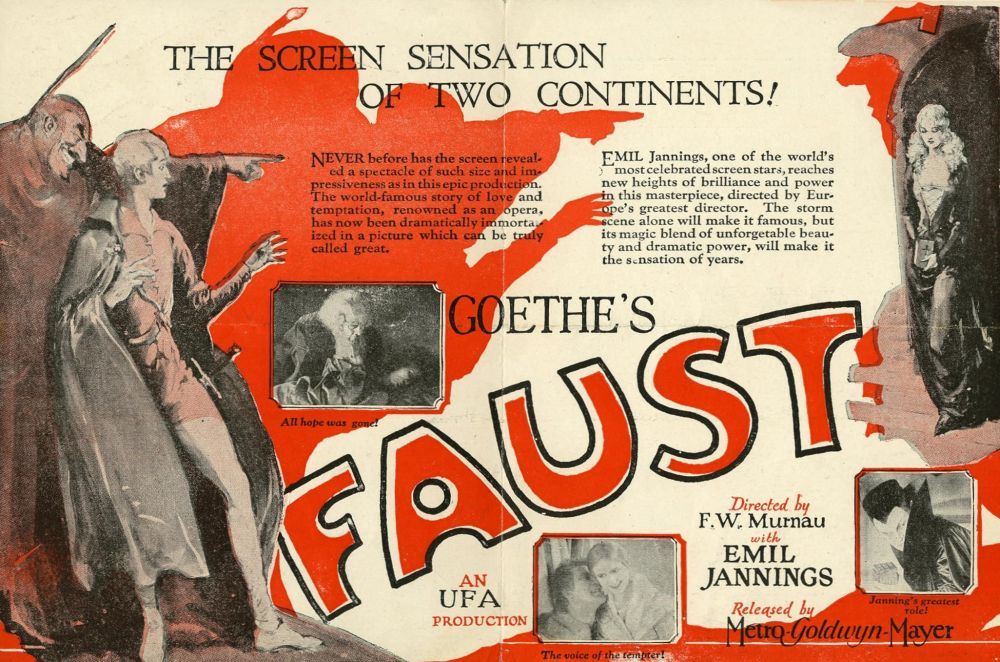

Murnau wasn’t first as far as cinematic adaptations of the story goes. At the very beginning of film, French pioneer Georges Méliès made several such movies, including Faust and Marguerite (1897), Damnation of Faust (1898), The Condemnation of Faust (1903), and Faust and Marguerite (1904). These gradually became longer and more complex. The last named runs for fifteen minutes, being a condensed version of Charles Gounod’s opera, with Méliès himself playing the role of Mephistopheles. Murnau draws both on Goethe’s telling of the story as well as other versions in what was, at the time, the most expensive movie made by production company UFA. That will tend to happen when you hire a winner of the Nobel Prize for literature, Gerhart Hauptmann, to write your intertitles, pay him 40,000 RM (the equivalent of almost $10,000 at the time) – then decide not to use them.

This would be Murnau’s last film in Germany, four years after the release of Nosferatu. He’d then head to Hollywood, and make films for Fox, beginning with Sunrise, which was named “Best Unique and Artistic Picture” at the first Academy Awards. It was the only time that category was ever presented, and is not to be confused with the “Outstanding Picture” Oscar, won that year by Wings. However, the director’s time in Hollywood would be brief. He was killed in a car accident in 1931, after only making four films in America. Weirdly, Murnau’s grave back in Germany was broken into and the skull stolen in 2015. Nobody has been charged in connection with the act of desecration, and the skull has yet to be recovered. If that creepy fact wasn’t enough to keep me awake during the movie, I had a stock of caffeinated beverages on standby.

And… yeah. I did stay awake. But let’s be honest. Good chunks of this were a chore to get through, and it does largely demonstrate my issues with silent movies, such as the tendency towards over-acting. I get it: you can’t express emotions through dialogue. Does this really mean you have to pull faces like you’re taking part in the World Gurning Championships? The basic plot is this. A demon, Mephisto (Jannings) makes a bet with an archangel over the soul of Faust (Ekman), dominion over Earth going to the winner. Initially, Mephisto seems to be winning, his “trial offer” luring Faust in, the devil then making Faust young again, to enjoy the pleasures of the flesh. But Faust’s love for a good woman, Gretchen (Horn), might stand between Mephisto being able to cash in his wager. Because this could be the origin of the “Power of love” trope.

I would be inclined to describe Mephisto as looking like someone ordered Bela Lugosi on Temu, except we’re still a few years too early for that. But part of the problem is a weird subplot in which the devil gets stuck in some kind of relationship himself. I’m not sure at all what the point of this was, perhaps simply indicating that ill-judged efforts at comic relief have been around since before the talkies. My other issue is that neither Gretchen nor Faust seem like the type of people who would inspire the kind of overpowering love necessary. She is a bit of a slut, and also a terrible mother, leaving her child to die in the snow. Admittedly, this may be due to a Mephisto-inspired hallucination, though regardless, dumping your baby into a snowdrift should certainly raise questions with Child Protective Services. Horn’s lack of experience – she had previously only been a stand-in – doesn’t help.

Faust doesn’t seem to have many redeeming features either, except for a halfhearted effort to use the pact to save his village from plague [a theme which has some echoes of Nosferatu]. This ends in a low-energy stoning, and thereafter, he’s not exactly heroic. Visually, there are some striking moments, in particular the sequence where Mephisto flies Faust across the landscape, showing him everything he could have in exchange for his soul. But if it feels like the creators were making the techniques for this up as they went along, it’s largely because, by most accounts, they were. It drags terribly in the middle, when the focus drifts away from the central struggle between Mephisto and Faust, and in general, whenever the film can’t lean on Murnau’s cinematic style. A commercial failure on its release, this is evidence that even a hundred years ago, film-makers were creating movies that looked good, but lacked a capacity to move the audience emotionally.

This article is part of our October 2025 feature, 31 Days of Vintage Horror.