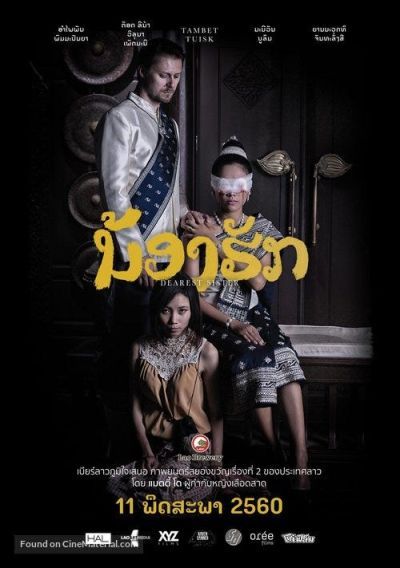

Rating: C-

Dir: Mattie Do

Star: Amphaiphun Phommapunya, Vilouna Phetmany, Tambet Tuisk, Manivanh Boulom

a.k.a. Nong Hak

So, what do we know about Laos and Laotian cinema? To be frank, beyond it being in SE Asia… not a lot. Just to the left of Vietnam, and above Cambodia, basically. It got blown to fuck during the Vietnam War for strategic purposes – close to a ton of ordinance per inhabitant were dropped by the US. It went Communist, and is one of the few remaining Marxist-Leninist states. Probably related: it’s economically in the shitter. The double-whammy of ideology and economy led to statements like, “Laotian cinema does not exist”, being made as late as 1995. Laotian horror cinema took even longer to be born. The first such feature was made in 2012, Chanthaly, also directed by Mattie Do. She’s still Laos’s only female director.

Do was born in the US, her parents having fled the country during the Communist revolution. After her mother passed away, her father returned to Laos in 2008, and Mattie and her husband followed. Chantaly was her debut film, having previously worked on sets as a make-up artist. She basically figured it out on the fly, and said, “I’ve got something like 50 hours of footage from my trial and error process of making my first movie.” Four years later, she made Dearest Sister, which became Laos’s first ever submission to the Foreign Film category at the Academy Awards. I did wonder quite how the Marxist government censors reacted to this American-born woman dropping horror scripts on their desks. To my surprise, she says they got used to it.

I’ve learned that censorship in Laos is really not a huge problem compared to other countries where it’s just a hard pass. At least in Laos, I can talk to them and figure out how to tell the story I want to tell. Like, they don’t want me to do political content where I’m commenting negatively on politics or the government in Laos, and they don’t want me to do pornography (which would make me really awkward anyway). But they are really worried about violence, and I have to toe that line with them. They’re getting better about it because, from my first film to my second to now, I’ve drawn that line farther and farther down the sand, and they know it. Now they’re just like, “how many bodies this time, Mattie?”

I’ve enjoyed reading about Do’s life, her approach to cinema, and greatly respect how she’s breaking new ground by making these movies in Laos. On the basis of this, I just wish I liked the film a bit more. It’s hard to know how much the official limits on violence mentioned above affected things here. But it’s an awkward combination where a film isn’t allowed to show explicit gore, and the maker (potentially due simply to Do’s lack of experience) isn’t adept at generating the subtler elements of suggestion. Stephen King talked about the three components of the genre: the Gross-out, the Terror and the Horror. When two of those weapons are removed from your locker, it becomes an uphill struggle for a movie.

I’ve enjoyed reading about Do’s life, her approach to cinema, and greatly respect how she’s breaking new ground by making these movies in Laos. On the basis of this, I just wish I liked the film a bit more. It’s hard to know how much the official limits on violence mentioned above affected things here. But it’s an awkward combination where a film isn’t allowed to show explicit gore, and the maker (potentially due simply to Do’s lack of experience) isn’t adept at generating the subtler elements of suggestion. Stephen King talked about the three components of the genre: the Gross-out, the Terror and the Horror. When two of those weapons are removed from your locker, it becomes an uphill struggle for a movie.

The core story feels like it could be an adaptation of a Thomas Hardy novel. A poor young woman goes to the city, seeking employment to help her family, only to find herself trapped in a worse situation than the one she left. Here, the main character is Nok (Phimmapunya), who moves to the Laotian capital of Vientiane to take a job helping out her cousin, Ana (Vilouna). She is married to a European engineer, Jakob (Tuisk – which does help explain the unexpected Estonian co-production in the opening credits!), but Ana is gradually losing her sight. Her ailment isn’t one which the film makes immediately apparent, something which was a mild source of confusion for me.

What Nok’s role is supposed to be, is also unclear, since there’s already a maid present (Boulom), who takes a swift dislike to the new arrival. Ana’s condition comes with an unusual side-effect: visits from spirits of the departed, who give her cryptic numerical messages. Nok eventually figures out that these are the winning numbers in the local lottery. Quite why the spirits of the dead would come all the way back over the great divide, to impart these numbers to someone like Ana who doesn’t even play the lottery, is never explained. Ghosts gonna ghost, I guess. The problem is, there’s treatment for Ana’s eyesight ailment on the horizon. A cure will potentially cut off Nok’s supply of gambling advice from the afterlife, and thus her new-found wealth.

It perhaps works better as social drama than horror, contrasting the urban sophistication of Ana with the rural naivety of Nok. The former is wealthy by local standards, though this is under threat due to a looming audit of Jakob’s shady business practices. This may require a swift exit from Laos, something Ana is not happy about. Meanwhile, about the first thing Nok does with her supernatural winnings is buy a swanky new cellphone. By the time the film reaches its dark conclusion, there isn’t so much to separate them any more. However, some other angles, like Jakob’s corruption, peter out without resolution, leaving the whole thing feeling unfocused.

It perhaps works better as social drama than horror, contrasting the urban sophistication of Ana with the rural naivety of Nok. The former is wealthy by local standards, though this is under threat due to a looming audit of Jakob’s shady business practices. This may require a swift exit from Laos, something Ana is not happy about. Meanwhile, about the first thing Nok does with her supernatural winnings is buy a swanky new cellphone. By the time the film reaches its dark conclusion, there isn’t so much to separate them any more. However, some other angles, like Jakob’s corruption, peter out without resolution, leaving the whole thing feeling unfocused.

The horror elements likely reach their peak when Ana is visited by the blood-spattered and badly damaged ghost of her dead mother (above). Which is a bit concerning, since her mother is still alive. Though as peaks go, this is closer to something you would find in the Lake District on a Sunday stroll, rather than anything Himalayan. It’s possible the approach plays considerably better to a local audience, who literally will never have seen anything like this before. A jaded Western viewer such as myself, while finding it an interesting glimpse into a country I’d never “visited” before, may be underwhelmed by the relatively toothless approach taken to its horror.

This review is part of our October 2024 feature, 31 More Countries of Horror.