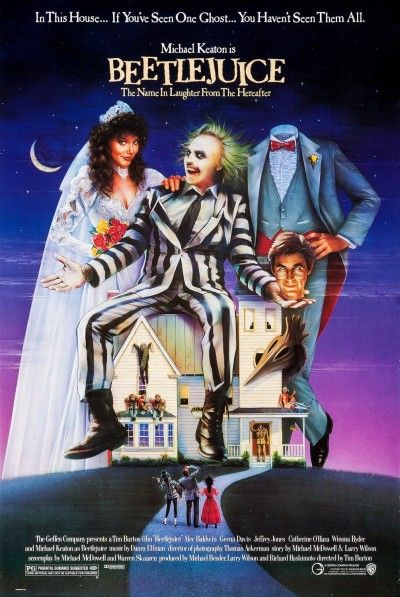

Rating: B

Dir: Tim Burton

Star: Michael Keaton, Geena Davis, Alec Baldwin, Winona Ryder

Rewatching this for the first time in what feels like forever, what stood out was how little the title character (and let’s not get into the whole spelling thing, please!) is on-screen. All told, barely seventeen minutes, but the impression he makes is undeniable. Weirdly, who Beetlejuice (Keaton) reminds me of more than anyone else, could be Ruby Rhod from The Fifth Element. Both are immensely irritating characters, of whom a little goes a very long way. Yet that’s kinda the point, and you absolutely will remember them. As we career towards the election, I’m also tempted to see a metaphor for the current American political situation, where… No. Let’s not go there. No good can come of it.

Instead, let’s focus on this being the film which broke Tim Burton. While not his first feature, it’s the one where his style really blossomed, and you can see many elements which would become staples of his work. I mean, if Ryder isn’t “Helena Bonham-Carter didn’t return my calls,” I don’t know what to say. Visually it’s the same sense of hyperrealism, despite depicting things far beyond the boundaries of reality, painting everything as if it were a candy-coloured nightmare. It’s one of the things elevating what could easily have become a fairly generic “ghosts try to scare away the living” story, especially with the kinda bland performances of Davis and Baldwin as the Maitlands, the late couple in question.

Yet, they probably need to be, operating as straight men to the grandstanding favoured by just about every other character. Certainly not just Beetlejuice, with Lydia Deetz (Ryder) loudly proclaiming, “My whole life is a dark room,” or Catherine O’Hara as Delia: “If you don’t let me gut out this house and make it my own, I will go insane, and I will take you with me!” It’s all very performative performance: I’m not sure I’d want to spend much longer than ninety minutes with any of them. Under the circumstances, hard to blame the Maitlands for taking the nuclear option and loosing the ‘juice, despite the clear risk of the cure being worse than the disease.

Yet, they probably need to be, operating as straight men to the grandstanding favoured by just about every other character. Certainly not just Beetlejuice, with Lydia Deetz (Ryder) loudly proclaiming, “My whole life is a dark room,” or Catherine O’Hara as Delia: “If you don’t let me gut out this house and make it my own, I will go insane, and I will take you with me!” It’s all very performative performance: I’m not sure I’d want to spend much longer than ninety minutes with any of them. Under the circumstances, hard to blame the Maitlands for taking the nuclear option and loosing the ‘juice, despite the clear risk of the cure being worse than the disease.

It’s a delight to watch pure, unfettered imagination pouring out on the screen, whether or not it’s strictly relevant to the story. The depiction of the afterlife as a hellish, convoluted bureaucracy is such genius, it deserves further exploration, and could have sustained an entire movie; here, it’s just one element. However, in the end it’s Keaton’s film, and it’s now impossible to think of anyone else in the role – least of all, perhaps, Burton’s original choice of Sammy Davis Jr. There’s a chaotic intensity to the portrayal of a character who is almost as much antihero as villain, but there’s no denying, the film finds a new gear (arguably, several) whenever he pops up. Not every eighties fantasy film has survived the test of time: I’d say, this one definitely has.