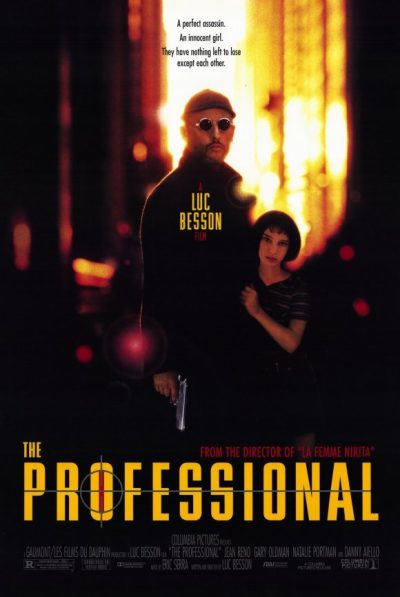

Rating: A

Dir: Luc Besson

Star: Jean Reno, Natalie Portman, Gary Oldman, Danny Aiello

This may be the greatest opening to a film ever, as Léon (Reno) accepts a mission from his Mafia mentor, Tony (Aiello), and carries it out. He doesn’t just slide into a hotel, kill all the henchmen and deliver a crystal-clear message that the New York presence of “Mr Jones” is unwanted. No: Leon does so, only after getting the henchman in the lobby to call up and warn the boss of his impending arrival. It demonstrates self-assurance of the highest level, and is filmed in a way so that the audience don’t clearly see him at any point. It brilliantly establishes Léon as a mythic, near-superhuman “ghost faced killer”. Then we meet Léon, and it flips the script completely.

For he’s a middle-aged man-child, who loves movies from the Golden Age of Hollywood and his pot plant in equal measure, while living alone in his apartment, drinking milk and sleeping in a chair. A less threatening creature, it’s hard to imagine – especially in contrast to the film’s antagonist, Stansfield (Oldman). For he too is initially hidden from the audience, as he and his cronies quiz Léon’s neighbour as to why the drugs they gave him, are no longer pure. When no good answer is forthcoming, we discover Stansfield is a highly dangerous animal: a volatile psychopath, with a fondness for pharmaceuticals. Yet, like Léon, there’s an odd quirk – a fondness for classical music. This helps set him apart from the usual “Bad Lieutenants”, because we eventually also discover Stansfield is not the mob boss we initially expect, but a corrupt and very rogue DEA agent.

The subsequent slaughter ends the life of not just the perp, but his wife and two of the three children. The exception is Mathilda (Portman, in her feature debut), who is reluctantly granted refuge in Léon’s apartment. She may be a truant, but has won the attendance prize at the school of hard knocks, asking him, “Is life always this hard, or is it just when you’re a kid?” Discovering his day-job (he doesn’t exactly do much to hide it), she offers to hire him to kill her family’s killers. Not that she liked most of them, mind, save her baby brother: “What the hell did he do? He was four years old.” Though he declines the job, she convinces him to take her on as an apprentice, with the eventual aim of taking revenge herself.

The subsequent slaughter ends the life of not just the perp, but his wife and two of the three children. The exception is Mathilda (Portman, in her feature debut), who is reluctantly granted refuge in Léon’s apartment. She may be a truant, but has won the attendance prize at the school of hard knocks, asking him, “Is life always this hard, or is it just when you’re a kid?” Discovering his day-job (he doesn’t exactly do much to hide it), she offers to hire him to kill her family’s killers. Not that she liked most of them, mind, save her baby brother: “What the hell did he do? He was four years old.” Though he declines the job, she convinces him to take her on as an apprentice, with the eventual aim of taking revenge herself.

After this brisk opening, the film then enters a more subdued middle section, during which time Mathilda and Léon bond. The relationship between the pair was the subject of much controversy, and largely led to the film being edited down from 133 to 110 minutes for initial release, in response to a poor reaction at test screenings in Los Angeles. If anything, it perhaps seems even more questionable now, in the post Jimmy Saville era. Admittedly, it’s very clearly specified that Léon is absolutely not interested in her, despite Mathilda virtually begging him to sleep with her. But even allowing for the European sensibilities of Besson, the sight of the 12-year-old Portman doing a Madonna impression or vamping it up as Marilyn Monroe is kinda creepy. It doesn’t help knowing that Besson was then married to Maïwenn Le Besco, whom he got pregnant when she was 15 and he more than twice her age. [Le Besco has a minor role here, playing Mr. Jones’s hotel prostitute]

However, the cuts weren’t just to tone done the relationship: a lengthy sequence which depicts them going on multiple jobs together was removed too. This is particularly important, since it sets up both the “ring trick” of the climax, plus the scene where Matilda believes herself ready for her own attempted hit on Stansfield and his crew in the DEA office. In the originally released version, the latter comes relatively out of nowhere, though in both, it’s hard to tell the time-frame. Are they hanging out for weeks? Months? It doesn’t really matter, in the end. Léon has to rescue Matilda from her ill-conceived scheme, and the film then kicks it back up for the grandstand finale.

Besson had already proven his action chops with Nikita, and hones them to an even higher level here, as Stansfield sends everyone (“What do you mean, everyone?” “EVERYONE!!!!”) into the apartment building where Léon and Matilda have been living. It’s a master-class in the art of escalation. The end of the resulting siege is almost as perfect as the opening: poignant yet triumphant, and probably the only time a movie has made me want to cheer and burst into tears simultaneously. It’s interesting to note that through all the carnage (and even in the extended version of the film), Matilda never shoots anybody with anything more than paint. Although this was not the case in the original version of the script, it seems Leon was intent on protecting her from the consequences. As he puts it, “Nothing’s the same after you’ve killed someone. Your life is changed forever.”

The three lead performances here are all near-perfect. They’re completely different in tone and approach, yet mesh beautifully to create something which feels greater than the sum of the parts. It’s probably Oldman who is the key. Both Matilda and Léon are, to varying extents, Besson revisiting characters from Nikita. But that film lacked any particular villain, beyond the faceless establishment that was intent on crushing the heroine’s spirit. The void is filled perfectly here by Stansfield, with Oldman often flying by instinct. For example, his the famous delivery of the “Everyone!” line was improvised, and when he’s interrogating Matilda’s Dad in Stansfield’s first scene, the father’s discomfort is largely genuine, because the actor playing him did not realize Oldman would be getting so close.

Slight qualms about the Matilda/Léon aside, this remains as wonderful as it was when I first saw it, as the London Film Festival’s closing night movie in 1994. It’s a great action film, yet is one with a huge amount of emotional heart, and also combines European and Hollywood styles of cinema in a way rarely attempted, and even less often successfully accomplished.

[February 2010] Besson had been building towards top-class action potential through his first four features, and finally hit the bullseye with the fifth. While set in New York, it’s a concept that could never be made in Hollywood: not so much for the mob killer being the hero, as for the 12-year old (Portman, in her feature debut) who accompanies him, after her family, who live next door to Leon (Reno), is wiped out by Oldman and his posse of corrupt DEA agents. The transgressive potential of their relationship – even if never realized – was enough to get it shorn of 25 minutes for its US release as a result.

[February 2010] Besson had been building towards top-class action potential through his first four features, and finally hit the bullseye with the fifth. While set in New York, it’s a concept that could never be made in Hollywood: not so much for the mob killer being the hero, as for the 12-year old (Portman, in her feature debut) who accompanies him, after her family, who live next door to Leon (Reno), is wiped out by Oldman and his posse of corrupt DEA agents. The transgressive potential of their relationship – even if never realized – was enough to get it shorn of 25 minutes for its US release as a result.

But looking at it now, it’s clear that Leon could never even contemplate such a possibility, and for the vast bulk of the time, it comes over more as a father-daughter movie than anything else. As such, it’s one of the most tender, completely platonic relationships ever in an action movie. All three leads are amazing. Portman delivers one of the best by an actress her age (she was only eleven when cast), while Leon’s stoicism is betrayed almost entirely by the emotions he puts over in his eyes. The latter’s stillness is a particularly-sharp contrast to Oldman, who chews the scenery to marvellous effect. I’ve realized how, in many of my favourite films, the villain is one of the most memorable aspects, and that’s true here, in spades: Oldman’s Stansfield is a complete loose-cannon, who could do anything to anyone at any time, and that’s what makes him dangerous, combined with rat-like cunning.

There isn’t an aspect of the movie that’s less than a joy, from the beautifully-fluid cinematography through to Eric Serra’s marvellous score, and the final assault, in which an every-increasing stream of SWAT men assault Leon’s apartment, is one of the most beautifully-choreographed and paced action sequences of all time. [Not least for Stansfield screaming, “Bring me everyone… EVERYONE!“] And the moments which follow it, with Leon heading out of the darkness and into the daylight, provoke tears and cheers in closer proximity than any other movie I’ve seen.