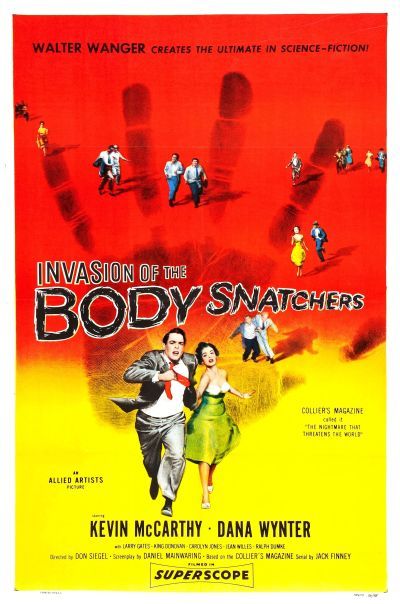

Rating: B-

Dir: Don Siegel

Star: Kevin McCarthy, Dana Wynter, Larry Gates, King Donovan

As mentioned in my review of the 1978 remake, it feels like we’re about due for another version of the story. Possibly overdue: we went fifteen years between the first remake and Abel Ferrara’s Body Snatchers, then fourteen before The Invasion. That was in 2007, so… Warner Bros were reported to be developing a fourth remake in 2017, and Justin Lin was said to be directing in October 2023. Not a peep since, but it feels only a matter of time. For this is the kind of story which feels easy to make topical and relevant. I suspect, throughout history, every era has had its causes for paranoia and disconnection from society, it’s just the flavour of these which varies.

We should therefore probably start off by looking at the state of the world in February 1956, when the film was released. That month saw infamous Soviet spies Guy Burgess and Donald McLean resurface in Moscow after vanishing for five years; on the other hand, some guy called Elvis Presley had his first hit, with Heartbreak Hotel. America generally was in flux, coming to terms with the recent desegregation of education, which still had not been fully accepted. Though it’s worth noting that McCarthyism, and its associated witch-hunts, was well past its peak by this point. That’s a topic we’ll return to later. President Eisenhower had met Stalin’s successor, Georgi Malenkov, in Geneva the previous July. But tensions were high, and wouldn’t be helped by the Russian invasion of Hungary later that year.

It was against this backdrop the film was made, filmed in March and April 1955, with Sierra Madre mainly standing in for the fictional location of Santa Mira. It’s one of the changes from the original source material, Jack Finney’s serial which had originally appeared in Collier’s magazine. It was set in the real town of Mill Valley, where Finney then lived – this was considered as a location, but proved too expensive. The story was set in the then-distant future year of 1976, and has a considerably more optimistic ending. In it, the alien species give up on their plan in the face of stiff resistance from us Earthlings, and return to space, presumably to seek an easier target. There’s an explicit parallel drawn between their behaviour – strip-mining locations for resources and wiping out the local population – and those of the humans they imitate.

It was against this backdrop the film was made, filmed in March and April 1955, with Sierra Madre mainly standing in for the fictional location of Santa Mira. It’s one of the changes from the original source material, Jack Finney’s serial which had originally appeared in Collier’s magazine. It was set in the real town of Mill Valley, where Finney then lived – this was considered as a location, but proved too expensive. The story was set in the then-distant future year of 1976, and has a considerably more optimistic ending. In it, the alien species give up on their plan in the face of stiff resistance from us Earthlings, and return to space, presumably to seek an easier target. There’s an explicit parallel drawn between their behaviour – strip-mining locations for resources and wiping out the local population – and those of the humans they imitate.

Finney hadn’t been the first author in the decade to use similar themes. Robert Heinlein’s 1951 story, The Puppet Masters, had also explored the idea of a clandestine alien invasion, run by parasites rather than duplicates. Philip K. Dick had used the replacement pod idea in his 1953 work, The Father-thing, though the invasion there was limited to a single family. Around the same time as Body Snatchers was being filmed, the BBC made Quatermass 2, later remade by Hammer, where another alien invasion by stealth has to be foiled. Perhaps most intriguingly, there is a genuine, though rare, psychiatric disorder, called Capgras delusion. Typically the result of damage to the brain, the patient is convinced a close relative or friend has been replaced by an imposter.

This all feeds into Siegel’s adaptation, in which town physician Dr. Miles Bennell (Siegel) returns from a convention. He finds increasing reports of exactly that: people are convinced family members are literally no longer who they were. Initially, he writes these off as, indeed, delusional. But after he and girlfriend Becky Driscoll (Winter) are summoned to the house of friend Jack Belicec (Donovan) to find a body which is slowly transforming into Jack (below), they can no longer deny something very weird is up. Further large objects, resembling seed pods (top), are discovered, and Miles eventually realizes this is the advanced guard of an alien invasion, gradually taking over the town by replacing humans with emotionless duplicates. As the doctor seeks to escape Santa Mira and raise the alarm, can anyone except Becky be trusted? And in the long run, even her?

This has been seem as a allegory by both the left- and right-wings: either as reflecting the dangers of McCarthyism, or diametrically opposite, a warning about totalitarian regimes, such as Communist Russia. But this may be a case of people seeing what they want to see. One of the film’s producers, Walter Mirisch denied any such message was intended: “From personal knowledge, neither [co-producer] Walter Wanger nor Don Siegel, who directed it, nor Dan Mainwaring, who wrote the script nor original author Jack Finney, nor myself, saw it as anything other than a thriller, pure and simple.” Siegel has said there is meaning, albeit more social than a political one: “I think so many people have no feeling about cultural things, no feeling of pain, of sorrow.” Finney’s fears, similarly, seem to be more about the dehumanizing effect of modern life, rather than a partisan philosophy.

It’s a killer concept, to be sure, and you can see its appeal across multiple generations. However, I feel like the 1978 adaptation has aged better. The cast are generally better, though McCarthy is good enough, and there are a number of elements here which – while probably an accurate reflection of small-town American life – now seem more distracting. For instance: full-service gas stations where you can just tell someone to put the fuel on your tab, and drive off. That prompted a discussion with Chris over how times have changed, over the almost seventy years since its release. The presence of Morticia Adams from the Addams Family TV show, playing Jack’s wife Teddy, cannot be unseen. Meanwhile, Sam Peckinpah – yes, that one – shows up as a gas meter reader. He was also a dialect coach on the production, though his claims to have rewritten the script appear unfounded, and led to a nasty spat with Mainwaring.

It’s a killer concept, to be sure, and you can see its appeal across multiple generations. However, I feel like the 1978 adaptation has aged better. The cast are generally better, though McCarthy is good enough, and there are a number of elements here which – while probably an accurate reflection of small-town American life – now seem more distracting. For instance: full-service gas stations where you can just tell someone to put the fuel on your tab, and drive off. That prompted a discussion with Chris over how times have changed, over the almost seventy years since its release. The presence of Morticia Adams from the Addams Family TV show, playing Jack’s wife Teddy, cannot be unseen. Meanwhile, Sam Peckinpah – yes, that one – shows up as a gas meter reader. He was also a dialect coach on the production, though his claims to have rewritten the script appear unfounded, and led to a nasty spat with Mainwaring.

Famously, the original pessimistic ending was changed. Initially, it ended with the hero screaming “They’re here!” at traffic on the freeway, but this was deemed too downbeat. A wrap-around segment was added, which saw Dr. Bennell instead telling his story and successfully convincing the authorities of the threat. Siegel was unimpressed, but from a commercial viewpoint, I can see the studio’s point of view. That kind of ending would remain a tough sell nowadays, and the new one remains open, certainly nowhere near as decisive a resolution as Finney’s book. It does help that compared to other fifties genre entries, this relies less on special effects. On the other hand, it means there’s less room for improvement. If Lin’s version sees the light of day, it’ll do well to improve on a film made over fifteen years before the director was born.

This article is part of our October 2025 feature, 31 Days of Vintage Horror.