Rating: C+

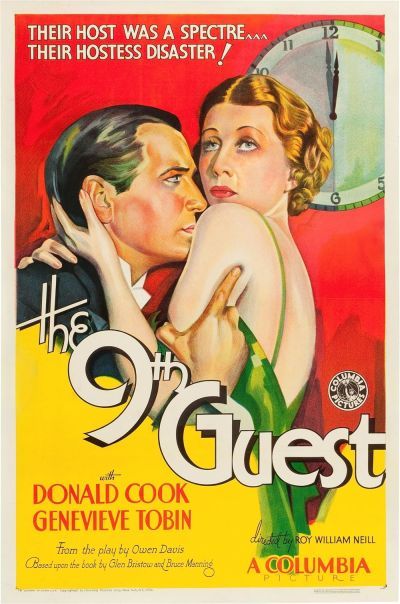

Dir: Roy William Neill

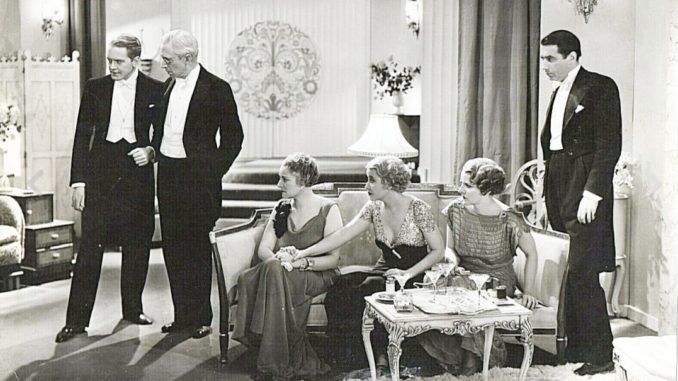

Star: Donald Cook, Genevieve Tobin, Hardie Albright, Edward Ellis

The concept of a group of people in a confined location, being picked off one by one, by persons unknown, is not a new one. Many people would trace its origins to a certain, unfortunately named Agatha Christie novel of 1939, subsequently published with a less incendiary title, And Then There Were None. But this movie indicates that Christie certainly didn’t invent the idea wholesale. Indeed, one wonders whether she lifted the core idea for her book from this movie. The film was itself based on a Broadway play of the same name, from the start of the decade, which was an adaptation of a 1930 novel, The Invisible Host by husband and wife authors, Bruce Manning and Gwen Bristow.

In this, eight members of New Orleans society are invited by telegram to a party in the penthouse of a building. They generally know each other, or at least of each other, and are not on good terms. The guests include recently fired campus teacher Henry Abbott (Albright), his girlfriend Jean Trent (Tobin), writer James Daley (Cook) and District Attorney Tim Cronin (Ellis), as well as mob boss Jason Osgood and socialite Margaret Chisholm. A voice on the radio introduces himself as the unknown host, and tells them there will be a ninth guest: “His name is death.” Naturally, it’s not long before the attendees are being thinned out – beginning with Osgood who is poisoned after cutting himself on a bottle of cyanide.

It’s all reasonably nicely constructed, and of course, this kind of thing was a lot easier to do in the thirties. Now, someone would whip out their cellphone and that’d be it. Here, cutting the sole phone-line is enough. Well, along with electrifying the exit, which leads to one of the deaths: it’s rather nasty for the time, the victim’s scream in particular quite chilling the blood as the current courses through their body in a shower of sparks. Sadly, there’s nothing in the rest of the film which has as much impact. Part of the problem is that the characters are largely not very likeable, being mostly upper-class types, from a time when class was a sharp divider in American society.

It’s all reasonably nicely constructed, and of course, this kind of thing was a lot easier to do in the thirties. Now, someone would whip out their cellphone and that’d be it. Here, cutting the sole phone-line is enough. Well, along with electrifying the exit, which leads to one of the deaths: it’s rather nasty for the time, the victim’s scream in particular quite chilling the blood as the current courses through their body in a shower of sparks. Sadly, there’s nothing in the rest of the film which has as much impact. Part of the problem is that the characters are largely not very likeable, being mostly upper-class types, from a time when class was a sharp divider in American society.

The eventual solution is moderately interesting exercise, involving advanced technology such as an auto-changing phonograph. This aspect would certainly be easier for any budding psychopath to manage these days, with an iPhone and Bluetooth-enabled speakers, so perhaps a remake could be arranged. There is scope for improvement in a number of ways, with the killer’s motive feeling a little light, in terms of the mass murder which results. Trying to introduce the eight characters also takes up too much time, in a film lasting only seventy minutes. I’d have started in the penthouse, brought them in from there, and let their interactions reveal their connections and personas. It’s notable more for its influence, as an early example of the whodunnit in cinema.