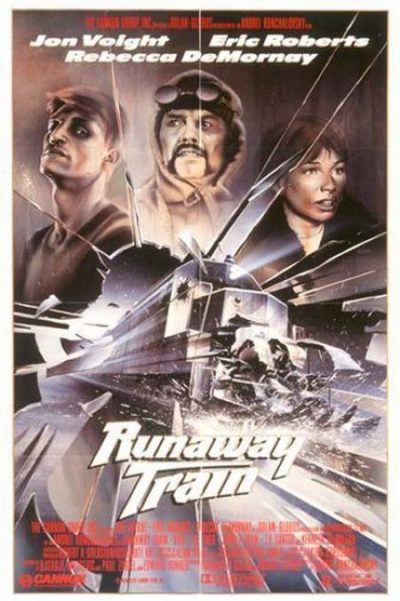

Rating: B-

Dir: Andrei Konchalovsky

Star: Jon Voight, Eric Roberts, Jessica De Mornay, John P. Ryan

Say what you like about Cannon Films, they would occasionally get it right. This would be one of those cases, though you wouldn’t exactly have expected it. I mean, I’d love to have been at the board meeting where they decided to hand a large sum to a Russian art-movie director, best known for adapting 19th-century literary works, to make a film about… Well, never say Cannon didn’t lay it out in their titles. When they included the word, “ninja”, you were sure to get a ninja. And when the title is “Runaway Train,” you know what you’ll be watching. However, it’s above the usual, since there’s more than the normal attention paid to the characters. Both Voight and Roberts were Oscar-nominated; the former as Best Actor, the latter as Best Supporting Actor, which makes little sense, considering they have almost identical screen time.

Rather than them being a device used to trigger mayhem, you sense Konchalovsky is more interested in the participants than the carnage. This is particularly clear at the end, which appears to be gearing up for a Really Big Crash, as you’d expected from your average action flick. Only, it’s never shown. You presume it happens. Somewhere. Off-screen to the right. This is the kind of wilful disregard for audience expectations you’d expect from a director whose previous film was Maria’s Lovers, in which World War II veteran John Savage is unable to consummate his marriage with Nastassja Kinski. [Nastassja causing erectile dysfunction? Suddenly, two escaped prisoners stuck on a train at 70mph seems thoroughly plausible in comparison]

Rather than them being a device used to trigger mayhem, you sense Konchalovsky is more interested in the participants than the carnage. This is particularly clear at the end, which appears to be gearing up for a Really Big Crash, as you’d expected from your average action flick. Only, it’s never shown. You presume it happens. Somewhere. Off-screen to the right. This is the kind of wilful disregard for audience expectations you’d expect from a director whose previous film was Maria’s Lovers, in which World War II veteran John Savage is unable to consummate his marriage with Nastassja Kinski. [Nastassja causing erectile dysfunction? Suddenly, two escaped prisoners stuck on a train at 70mph seems thoroughly plausible in comparison]

Manny Mannheim (Voight) is the toughest inmate in Stonehaven Maximum Security Prison. Due to multiple previous escapes, he has been welded in his cell for three years, until a civil rights case forces warden Ranken (Ryan) to put him back in the general population. It soon becomes clear that Ranken has it in for Mannheim, and his only chance of surviving is another escape. He does so, with the help of laundry trustee Buck McGeehy (Roberts), who decides to come along on the break. They cross the frozen wastes to a train yard, and stow away in the back. Unfortunately, the engineer suffers a fatal heart attack, and the failure of multiple systems intended to prevent exactly this scenario, lead to them being stuck on board with young railway employee Sara (De Mornay), and Ranken in hot pursuit.

I didn’t realize that this was based on an original screen play by, of all people. Akira Kurosawa. Back in the mid-sixties, he had been inspired by a 1962 article in Life magazine, describing a similar incident in which four cars had rolled out of control. It was intended to be his first foray outside of a Japanese studio, and the production was announced in June 1966, with a hefty budget for the time of $5.5 million. However, the director and producers were never able to get on the same page, creatively, and the film was scrapped later that year. A couple of decades later, after a failed Canadian effort to revive the script, it ended up in the hands of Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus at Cannon. It was then significantly rewritten by several writers, not least Edward Bunker, novelist and formerly San Quentin’s youngest inmate, and who appears in the film, shanking the inmate who tries to kill Mannheim on the orders of Ranken.

Bunker’s involvement proved significant in another way. Because speaking of cameos, you also get to see a very young Danny Trejo – sorry, “Daniel Trejo” according to the credits – who plays the boxer fighting McGeehy for the prison title. He had been visiting a friend – actually, a recovering drug addict who found himself tempted by the mid-eighties Hollywood quantities of coke floating around the set – and Bunker recognized him from their time together in San Quentin. On learning Trejo could box, the production hired him to help teach Roberts how to look credible in the ring. The rest, as far as Trejo is concerned, is history, though more than 25 years later, Trejo pointedly recalls, “I learned how not to behave on a movie set from Eric Roberts. He was very demanding.”

Given the film was made for less than $10 million, it looks very, very good, under director of photography Alan Hume, who did Return of the Jedi. It also, obviously, dates from an era before CGI and the practical effects are impressive. You get a real sense of physical mass as the train careers through the Alaskan wilderness. There’s an equally credible sense of danger as the participants clamber around the outside, trying to reach the front where the cut-off switch is located. Somewhat less effective, unfortunately, is Voight, who appears too self-consciously to be Giving A Performance, as if with one eye toward the Academy Awards [admittedly successfully, though he ended up losing out to William Hurt in Kiss of the Spider Woman]. Roberts and De Mornay both appear significantly more natural in their roles, and it’s caring about their fate which provides the film with a decent emotional heart, not often seen in the genre.

Given the film was made for less than $10 million, it looks very, very good, under director of photography Alan Hume, who did Return of the Jedi. It also, obviously, dates from an era before CGI and the practical effects are impressive. You get a real sense of physical mass as the train careers through the Alaskan wilderness. There’s an equally credible sense of danger as the participants clamber around the outside, trying to reach the front where the cut-off switch is located. Somewhat less effective, unfortunately, is Voight, who appears too self-consciously to be Giving A Performance, as if with one eye toward the Academy Awards [admittedly successfully, though he ended up losing out to William Hurt in Kiss of the Spider Woman]. Roberts and De Mornay both appear significantly more natural in their roles, and it’s caring about their fate which provides the film with a decent emotional heart, not often seen in the genre.

The biggest problem is probably the film’s climax, an utterly implausible scenario which sees Ranken climb down a rope ladder from a helicopter onto the train, to ensure Mannheim doesn’t get away. This would stretch disbelief, even if Ranken hadn’t just watched one minion get run over attempting the same feat, and actor Ryan wasn’t teetering on the edge of fifty at the time. Still, we’ll cut the film some slack since it’s essential for the payoff to get Ranken and Mannheim face-to-face. Certainly, the final image, of the latter standing on the roof of the train as it careers into an uncertain future (probably involving utter destruction(, will stick in your mind far beyond the last shots of most action film, followed by an entirely appropriate quote from Shakespeare:

“No beast so fierce but knows some touch of pity.”

“But I know none, and therefore am no beast.”